Introducing: Friction Arts, Birmingham

Charlie Bailey investigates a small but vital force in South Birmingham’s art scene; committed to making contemporary art relevant to the people who live there…

“We’re not interested in ‘trauma trawling’. Not in the kinds of art that goes into communities and points out everything that’s maybe bad there, without hearing all the wonderful things that they want to say as people, not as victims.”

As statements of intent go, it’s pretty ambitious. But it also epitomises the fierce sense of purpose that enlivens Sandra Hall, co-founder of Friction Arts collective. As passionate advocates of public art, Friction have made this motto into their lives’ work as artists. Established by Hall and Lee Griffiths nearly 20 years ago, Friction is committed to making contemporary art relevant to people in their city.

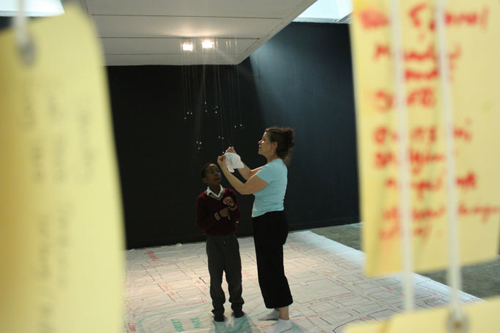

Visitors to Friction’s exhibition space and studio, The Edge, might find themselves talking with working artists and curious locals in amongst the sprawling, chaotic workspace; invited to a communal dinner to share food and their experiences; or taking in the skyline of Birmingham from the vantage of their rooftop.

Based in Digbeth, South Birmingham, Friction’s work has often been in dialogue with their surroundings: Inside Out’s art trail took in hidden gems from the historic district and re-contextualised them around people’s stories and memories. More recent projects, like Echoes from the Edge and Ben Nichols’ Parched Ground, make use of everything from personal testimony, found materials, photo documentary, and forgotten personal relics — like projector slides — to explore the region’s industrial legacy and its changing social fabric.

Hall and Griffiths both see this kind of local awareness as integral to their work as artists, alongside an attitude of openness and transparency: to not only bring people together for the work itself, but to do so in a way that respects the individual and their right to their own story.

“Our work is always centred around two concepts: interruption and engagement”, says Griffiths, grinning widely. Interruption, he explains, in the sense that they hope to prompt people who are complacent about the issues that face overlooked communities in the city, whilst also ensuring that ‘engagement’ really does mean that those communities have ownership over the work.

Friction’s methods are designed to draw out local experiences and cultures from inhabitants, rather than comment on them from an external perspective. Their attitude of listening to and reflecting on people’s stories and experiences in a organic, empathetic way is key to their attitude as artists: its a simple concept often overlooked in public arts by the need to fulfill some vague funding remit: that people talk and relate inauthentically when you approach them in an inauthentic way.

Rather than resort to methods and programmes that they see as ‘drive-by art’ inflicted on communities — as opposed to emerging from them — Friction’s work has included expansive oral history projects, explorations of Birmingham’s industrial heritage, and the repurposing of the city’s derelict and abandoned spaces.

The Digbeth area epitomises this last issue for Hall and Griffiths: Birmingham’s historic Irish quarter, where The Edge is located, is fast becoming an epicentre of cultural development for the city. In the last decade, Digbeth has flourished by attracting music venues, art groups, design studios and others into the existing mix of industry and housing.

“This is one of the last parts of Birmingham’s centre that still has manufacturing units and workshops, all side by side with artists, working families, and students”, says Griffiths. But that hard-won fact is coming under increasing pressure as major development plans for the city come into effect, and national infrastructure projects begin linking regional cities like never before.

A planned high-speed rail line between London and Birmingham (HS2) will have its terminal located within reaching distance of the street part of the city that has housed Friction Arts for its entire two decade history. It is expected to bring with it an influx of capital and people but there are very real concerns over the impact, which promises to be a gold rush for speculative investment.

“We’re realistic about the potential for poorly thought-out gentrification in the area,” says Hall, with some sadness. Digbeth and other de-industrialised areas of the city have offered architectural treasures as well as attractive rents to creative groups and industries. If it were to be torn down — “for the sake of a glorified commuter belt serving London”, laments Griffiths – the potential loss of low cost, big footprint workspaces in the city would be enormous.

Despite the sense that the city is changing apace, worn cliches about the region, rather than recent achievements, have remained the pop culture legacy of the largest metropolitan area outside of Greater London: British Leyland strikes, Black Sabbath and Balti; all that came to prominence in the 1970s and ’80s. In the consciousness of the British public, it’s still these archaic symbols that define the city.

“Residents need to be able to present what we’ve achieved here, how it’s essential to the city,” explains Hall. “If this city’s arts and culture are going to be something we can proud of, then we need to be able to articulate that [to local government]“.

Consultation and representation is difficult to achieve in negotiations with the largest municipal authority in the UK. Local councillors are, according to Hall and Griffiths, well-meaning and supportive, but in practice, funding models reward uncritical or explicitly commercial endeavours.

“We’ve found ourselves focusing a great deal on projects outside of the UK, as funding has dwindled”, says Griffiths, explaining that EU and international funding is the only practical way to survive when domestic art must provide safe, and easily identifiable ‘social capital’ returns (a metric which the UK government is eagerly applying to funding applications, but which no one can really define).

It’s easy to see why the people behind Friction Arts are so passionate about Digbeth whilst watching the sun go down on the city from the roof of The Edge: the area has emerged as the premiere creative hub for the region, through the hard work of committed people, with virtually no strategic support from government. It has brought people back to live in a part of the city that was left to decay as industry fled; and it has fostered a distinct identity as a part of Birmingham’s cultural melting pot.

Ultimately, whether it’s in arts practice, or planning for the future that’s coming over the horizon, the Friction Arts founders remain positive. “If it’s not work, it’s research; it’s about lived experience and bringing people with you on that journey”.

Charlie Bailey

This article has been specially commissioned for The Double Negative by Liverpool John Moores University and Arts Council England. Part of the collaborative #BeACritic campaign — see more here

More on Friction Arts here

Friction Arts takes part in Digbeth First Fridays – a multi-venue event on the first Friday of each month across Digbeth, with exhibitions, late-night openings, special events, culture in unexpected spaces, live music, street food and more. See Twitter for updates!