“Humour is really important in my work” — The Big Interview: Ella Kruglyanskaya

As her exhibition at Tate Liverpool comes to a close, and ahead of a new show at Tramway, Ella Kruglyanskaya talks us through the humour of her painted protagonists, and what it feels like to buck the trend as a living, female artist in the museum…

When was the last solo exhibition you saw by a 38 year-old woman at a major arts institution? Gender equality in the gallery and the workplace is a hot topic at the moment; with Iwona Blazwick, director of the Whitechapel Gallery in London, recently commenting: “I was just at the Kunstmuseum in Basel where they have just rehung the entire collection from 1900 to the present and I think there are five women. Sadly it is still an issue.”

With this in mind, Tate Liverpool has taken a behind-the-scenes decision to commission more female artists, with a specific focus on those making important contributions to art movements and those in the early stages of promising careers. Since Francesco Manacorda took the reigns as Artistic Director in 2011, there have been significant presentations of work by mass media artist Gretchen Bender (1951-2004), including her famous Total Recall (1987) installation; Indian Modernist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990); and Lancashire-born, surrealist artist and writer Leonora Carrington (1917-2011). 32 year-old Belgian-American digital artist Cécile B. Evans will premiere brand new work in the gallery in October this year.

And now, the aforementioned 38 year-old, Latvian-born, New York-based painter Ella Kruglyanskaya, in her first ever solo museum exhibition. What’s unusual about this show – of lively, and relatively saucy, figurative paintings, depicting a cast of women gossiping, holding guns, posing, and glaring — is that the work has been made over ten years, which is a relatively short period of time for an artist. Audiences can see the progressions and evolutions made by Kruglyanskaya with paint throughout her early career. It’s a rare moment to see a comprehensive appraisal of an artist’s portfolio at this stage, at an institution like this. But how does she feel about bucking the trend by being a living, female artist in the museum?

“That’s the nature of museum shows”, she tells me when I meet her in person at Tate Liverpool. We discuss how this situation is important to be aware of, but not so much that it should define the artist’s work. It’s annoying that gender inequality should even be a concern in 2016, but it is. “It starts to position you within a time continuum, so you start thinking of yourself as a historical being, which can be kind of unsettling. It’s not in a bad way, it just makes you look back.”

In retrospect, Kruglyanskaya sees Bathers (2006), below) as an important painting: “my breakthrough work”. Understanding this piece – of a brunette sunbathing on the beach — I gather is the key to the exhibition, which takes up the entire ground floor Wolfson Gallery space at the dockside gallery.

“I remember the decision to paint Bathers” she explains. “In a way it was throwing up my hands in the air and being like: ‘Well, I’m just gonna do the most obvious thing, which is tits and ass’. Humour is really important in my work. Also humour is a very modern feature of art. There is something quite modern in this attitude that we don’t take ourselves so seriously.”

Describing her fictional, principally female subjects as “protagonists”, this one has visible “tits and ass” because she is wearing a bathing costume; lying on her front on a mat, looking over her shoulder slightly past the viewer, with an undaunted (or is it irked?) expression. Perhaps she’s just caught our companion admiring her tits and ass as we walk along the beach.

All of Kruglyanskaya’s paintings make the viewer vividly aware of looking, or of the act of looking. It would be easy to reference Laura Mulvey’s Male Gaze theory — “In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female form” – but the Female Gaze in Kruglyanskaya’s work stares right back.

This performance of looking in Kruglyanskaya’s paintings also involve a snapshot of a moment in time; they are very suggestive of something going on outside the frame. The protagonists are, she notes, “used to evoke a feeling or an attitude, opposed to a representation of another human”, or (importantly) as opposed to a portrait.

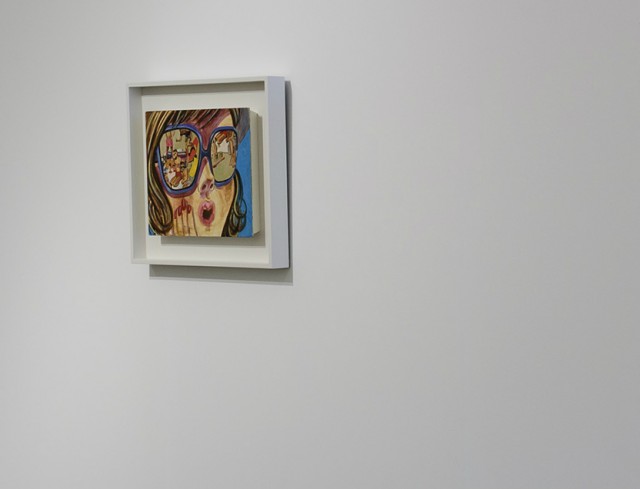

Girl with Sunglasses (2008), above) is probably the best example of this suggestive feeling; depicting a picture within a picture within a picture. We look on and on at a young woman’s face, composed of watery egg tempera, which takes up the whole of the panel; one hand touches her cheek, and her rosy-pink mouth makes an “O” shape in an expression of surprise. She wears a huge pair of sunglasses that reflects the beach scene in front of her — outside of the panel and beyond our gaze. The bronzed figures reflected in the lenses seem to wave at her in friendly greeting, so what is she so shocked about? Is it perhaps that she hasn’t seen them in a while, or is there something going on that we can’t see?

“I don’t believe that there is a story that’s outside that I know and no one else knows”, Kruglyanskaya tells me; “and that contributes something. I believe that what you see is what you get. If you see this, you have to read whatever is in there. It’s not a novel, not even like a photograph. A photograph is a snapshot of a continuous reality, whereas this is not. We cannot pretend a painting has a continuous reality where it does not.

“But to me, it’s really funny and interesting to create not an illusion, but a feeling; that something did happen or something is happening, and that you could project your own [story] into it. More maybe akin to a really good film poster, where you look at the poster and think: ‘What would this film be about?’”

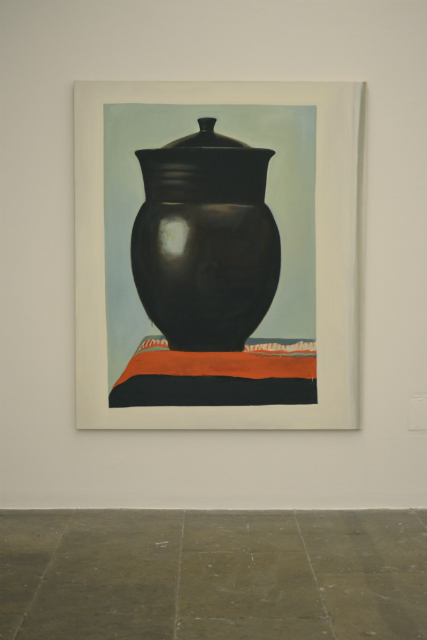

This picture within a picture technique acts out prominently in Kruglyanskaya’s new still-lifes: painted directly from pages of Walther Scheidig’s 1966 book Crafts of the Weimar Bauhaus 1919–1924: an Early Experiment in Industrial Design. Curvy coffee pots and jugs on fabric backgrounds emerge; the paper margins and torn page edges from the book can be clearly seen at the canvas edge. Kruglyanskaya applies paint in a sloppy, photorealist manner — leaving the odd drip to remind us that these are representations of 2D images, rather than the “real” 3D objects, that she has looked to again and again in a favourite publication. The functionality, visual beauty and aesthetics of the German-made kitchenware is captivating anyway, so make a good choice of subject; however, it is the application of the oil paint, combined with the huge scale (the canvases, and illustrated vases and jugs, are larger than the viewer), that keeps you looking.

“I like the contradiction that it’s not fussy, but at the same time it has this illusionistic effect”, she says; “our minds play that trick on us. It’s like a reproduction of a reproduction of a reproduction, it’s endless; so in a way it’s really important to see them in person.”

We laugh at the “very silly” thought that these endless reproductions might end up as postcards in the Tate shop: reproductions of more reproductions. These are very new works; shipped directly from the studio to Tate as the paint was drying. I ask Kruglyanskaya why Bauhaus has become a recent focus.

“I love Bauhaus design and the education. The Bauhaus is an important movement. It was, then, a very new kind of approach to form, and being very serious about even just the simplest things, like jugs and pitchers and textiles. I usually don’t paint directly from photographic images… for me, it’s like a layering of things; it’s my interest in still life. That’s how I was trained as a painter: I painted a lot of still lifes.”

I build up a picture in my mind of Kruglyanskaya working in the studio almost like a magpie; going back and forth to pick up previously satisfactory methods of working, and then trying something new. She agrees:

“Yeah, I think that I cannibalise my work a little bit! Because you distil the themes that you’re interested in, and then always go back to those themes. In a way, I try to speak for the things that I know well, and that are interesting. Obviously, there are other things that are interesting to me, but I have this experience of being a woman in the world and a person who likes to paint and draw, and so I look at the history of other things that were painted before me. It’s like a very basic urge to just continue that conversation in a different way.

“I reflect back on the things that exist around me visually, e.g. the way that the image of a woman is constructed — it’s funny to me because these women don’t exist, I just make them up, but it’s not out of nowhere because obviously it comes from all the things that I’ve seen. The absorption of pop culture, art history, the history of painting, and the culture of cinema, photography — all these things. I think they all play into each other, back and forth.”

And this “back and forth” reflects Tate Liverpool’s concurrent painting exhibitions: Kruglyanskaya, plus household name Francis Bacon (1909-1992), and the lesser-known Austrian artist Maria Lassnig (1919-2014). I visit each show, walking past wildly distinct and varied artworks. Asking: “In a world of technology, specifically post-photography, why do we paint?”, the three shows tie into the gallery’s “magazine principle” approach – whereby all exhibitions aim to relate to different parts of the building, connecting the whole creative programme and organisation’s ambitions, whilst making the art more accessible and the trip more valuable to the visitor.

This approach is so far working very well; there is a dynamic created between contrasting artists (in age, background, life experiences, practice, technique, etc.), presented on an equal stage, who happen to work somewhere in the same realm (medium, concept, etc.). There is a challenge posed to the viewer as a result; to become more active in making their own comparisons and interpretations.

There is no doubt that introducing more women artists into the gallery, who are working at a mid-point, or a crucial point, in their careers (and thus revealing some of the evolutions of making), enhances the visit; especially when juxtaposed by two prolific artists from other generations. It’s a big, brash viewing experience, and we just aren’t seeing enough of this kind of display globally. So please, Tate Liverpool, let’s see even more representation – let’s normalise living, female artists in the gallery, away from this idea of a space used only for “historical beings”. Let’s buck the trend.

Laura Robertson, Editor

See Ella Kruglyanskaya at Tate Liverpool, ground floor, 18 May-18 September 2016, and at Tramway, Glasgow, from 12 October-11 December 2016 — both exhibitions FREE

See Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms and Maria Lassnig at Tate Liverpool, fourth floor, 18 May-18 September 2016 — £9.50-12

Read Jack Roe’s Bacon, Lassnig & Kruglyanskaya: Tate Liverpool’s Summer Season — Reviewed

Images, top to bottom: install shot of the Bauhaus still lifes; Bathers (2006); install shot of Girl with Sunglasses (2008); Bauhaus still life; Large Bather with Paper Cutouts (2016) and Bathers (2006). Install images © Tate Liverpool, Roger Sinek