Bacon, Lassnig & Kruglyanskaya: Tate Liverpool’s Summer Season — Reviewed

Why do we paint? Jack Roe looks for answers inside and outside of the canvas with three invigorating, theatrical, and very human, artists…

The question that acts as a kind of leitmotif for Tate Liverpool’s summer offering is a succinct one, posed delicately during an introductory address provided by the gallery’s artistic director, Francesco Manacorda:

“In a world of technology, specifically post-photography, why do we paint?”

Like all good framing questions, it allows for wide-ranging interpretation and can be answered in as many ways as you’d care to attempt, but for an expansive and effective essay on the possibilities and continued significance of the medium, I’d suggest you head into the galleries.

In amongst such hallowed company as her work has found itself, it may be amongst the audience’s crueller instincts to view Brooklyn-based, Latvia-born Ella Kruglyanskaya‘s contribution with polite detachment; peering in on the ground floor before moving swiftly on to the heavyweights upstairs. That would, of course, be a huge insult to the artist and the work and, happily, there is enough vibrancy here to make such foolishness seem, well, foolish.

Kruglyanskaya’s paintings have the curious quality of being at once familiar and invigorating. Veering from stylized character studies that invoke Matisse and Patrick Nagel both, while retaining a more personalized vision, through cinematic caricature as in Girl With Sunglasses (2008), to brand new works depicting Bauhaus designs rendered in highly technical and oddly entrancing still-life. This is a decade-long retrospective containing work that, purportedly, was still drying on the canvas as it was shipped from the artist’s studio. This is a living, breathing collection of painting and it shows. One gets the impression of narrative hidden from the viewer; at one point I was struck by the curious idea that these works are a set-up to a punchline that only Kruglyanskaya knows.

The omnipresence of the female form lends an air of inevitability to the flavour of the discussion that the work will inspire, but this collection is beguiling enough that reaching towards more obvious conclusions seem somewhat dismissive. As stated so pertinently by the curator Stephanie Straine, the work of a living, breathing artist has a way of raising questions about where the work might head towards, rather than where it has come from, and that — like so much of this collection — is a joy in itself.

Upstairs, in the work of of Maria Lassnig, the notion of self looms large; a collection of 40 works spanning 70 years and focused almost exclusively on Lassnig’s view of herself, both within and without. If that sounds like a theme that may wear thin over the course of 40 paintings, be assured that it does not. Viewed in the whole, this is a fascinatingly honest portrayal of the internal life of an artist.

Born in Austria before spending time in Paris and New York, Lassnig’s paintings over this period are an unusual prism through which view the tumultuous 20th century, most obviously in the series of works created around the breakout of what is now to be called the First Gulf War. Historically significant of course, in the ways that armed conflicts always are; the way in which the First Gulf War was consigned to history is of particular import as it was the first war presented exhaustively through the medium of television.

The deadening, distancing effect of such a communication is discussed through a series of paintings from the 1990s, which are arguably the most affecting of the collection as Lassnig merges the human form with instruments of war, as she felt her humanity receding. It is often easier to ingest such wide-ranging ideas when they are reduced to a more personal context; something in which Lassnig succeeded admirably, as through presenting herself she provided a human window to the wider context, and a fascinating historical composition.

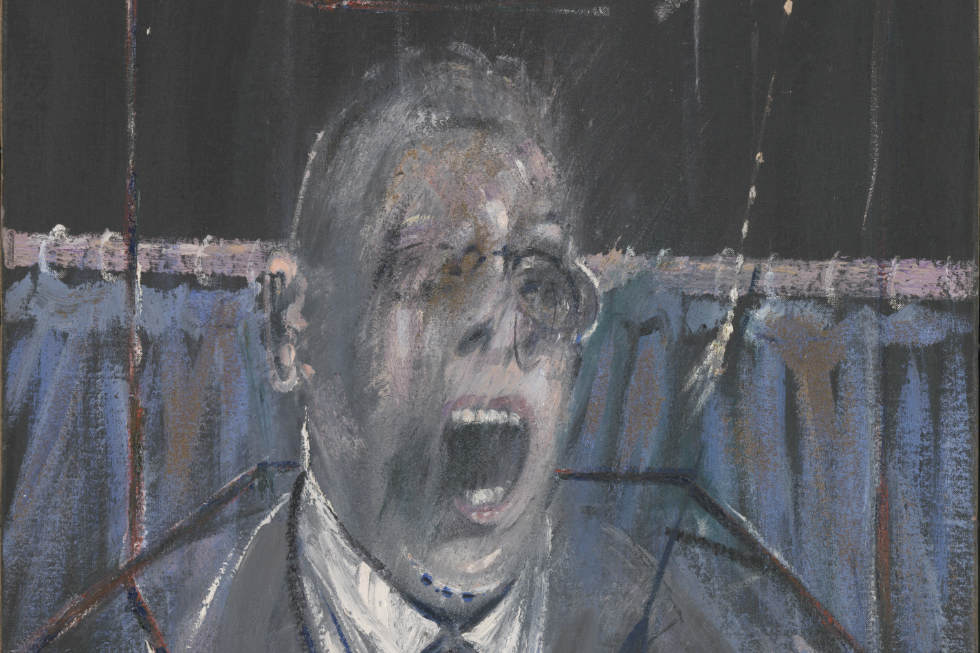

When dealing with artists that loom as large as Francis Bacon, especially one so eloquent, it can seem churlish to provide an insight to their work and almost foolhardy; there is nothing to be said about the man or his work that he didn’t say better himself. Yet, as is so often the case with accepted wisdom, it would be incorrect. Invisible Rooms is a breathtaking disquisition on one of 20th century British art’s biggest names, and regardless of how familiar you are with the subject matter, there is assuredly something here to make you think again. The hallmarks of his work are presented concisely, and a show spanning six decades allows room for everything.

The disturbing and ageless Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion that ensured as long ago as 1944 that Bacon’s name and work would survive the decades is here, along with works both iconic and obscure. What makes this collection stand apart is the length at which the process behind Bacon’s artworks is discussed, from boxes of notes and preparatory sketches — a practice which the artist denied during his life — to the presentation of an unfinished painting Untitled (3 Figures) (1981), which shows the formation of a composition but gives no clue as to its intended outcome. There are even photographs of his studio interior.

For an artist who so intentionally tried to avoid narrative readings of his work, who found it necessary to focus on the spontaneity of his efforts, this lifting of the curtain on this most theatrical of painters is exhilarating.

In truth, Tate Liverpool’s Summer Season provides no real answers to the question that frames it: “Why do we paint?” Instead, it suggests the impossibility of one simple answer and leads you gently towards the philosophical. We continue to paint for the same reason that we continue to communicate at all; because try as we might, we will always leave behind something that needs to be said.

Jack Roe

See Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms and Maria Lassnig at Tate Liverpool, fourth floor, 18 May-18 September 2016 — £9.50-12

See Ella Kruglyanskaya at Tate Liverpool, ground floor, 18 May-18 September 2016 — FREE

Images, from top: Large Bather with Paper Cutouts 2016 (left) and Bathers 2006 (right) by Ella Kruglyanskaya on display at Tate Liverpool from 18 May until 18 September 2016 © Tate Liverpool, Roger Sinek. Maria Lassnig, 1919-2014, Double Self-Portrait with Camera 1974 (Doppelselbstporträt mit Kamera) 1974 (detail), oil paint on canvas, 1800 x 1800 mm © Maria Lassnig Foundation © Artothek of the Republic of Austria, permanent loan, Belvedere Vienna. Francis Bacon, 1909-1992, Study for a Portrait 1952 (detail), oil paint and sand on canvas, 661 x 561 x 18 mm © Estate of Francis Bacon. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2016.