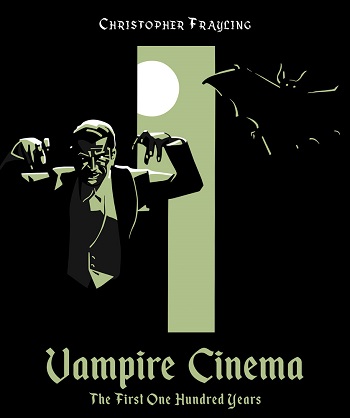

Vampire Cinema

The First One Hundred Years

“Scary, sexy and pretty fucking cool.” With Christopher Frayling’s new book on the subject as his guide, Mike Pinnington takes a look at a century in vampire cinema…

As a goth, I was a late bloomer. The thing that snared me, well into my late teens, was Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire. It was scary, sexy and pretty fucking cool. Still is. One of Rice’s creations, the complex vampire Lestat, embodies all of the contradictions of his kind. Beautiful, seductive and terrifying. Mercurial and thrillingly capricious, he is dangerous to know; those around him are both in thrall to and infuriated by him.

Lestat, via Rice’s book and director Neil Jordan’s 1994 adaptation, was my moonlit gateway to the children of the night. It is dark and blood-spattered territory, continually worth exploring, such is its metaphorical power and askance commentary on the human condition.

2022 marks a century of this iconic gothic figure on screen, a milestone celebrated by a new book – Vampire Cinema: The First One Hundred Years. Written by cultural historian and legendary commentator on the subject, Christopher Frayling (top), the visual history traces the genre’s beginnings to the ‘Age of Reason’ and learned discussions of accounts of vampirism emanating from Eastern Europe. Once the technology existed, it was a matter of time until we saw their image on screen.

With the sumptuously illustrated coffee table tome as departure point and partial guide, we thought we’d take a trip from 1922’s Nosferatu to renditions from this decade – not all of which are included in Frayling’s book. One thing is clear: although the nature of our fascination has changed over the years, we are still infatuated by the vampire, in all its guises.

Nosferatu, 1922, F.W. Murnau

A thinly-veiled adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, today we are lucky to have Nosferatu to refer to at all. Director F.W. Murnau’s film – considered the first and still one of the finest examples of all on screen vampires – like the creature on which it is based, seemed doomed not to see the light of day. Stoker’s widow Florence, suing for breach of copyright, had won a court order to have all prints and negatives of the film destroyed. There is a poetic beauty in Murnau’s study in horror via German Expressionism surviving to thrill generations of cinema goers. It is also important, observes Frayling, in that it “emphasised three elements of vampire lore [then] new to fiction and film: the idea that vampires as night creatures are destroyed by the light of dawn; that they are particularly vulnerable to a ‘chaste woman’ who is prepared to sacrifice herself; and that with their fellow-rodents they are carriers of the plague.”

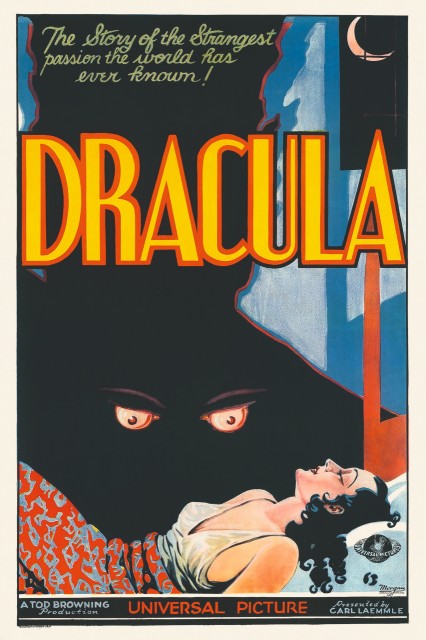

Dracula, 1931, Tod Browning

Less than a decade later, the vampire had morphed from barely humanoid ghoul into a debonair, albeit not to be trusted host. This was due in no small part to Bela Lugosi’s charismatic interpretation of the role in Tod Browning’s Dracula – with his slicked-back hair and dinner suit. As Frayling writes, it is a performance of “powerful presence and unorthodox line-readings (‘I bid you … welcome’)”. Much has been made of the Hungarian émigré Lugosi learning his lines for the film phonetically, but it’s hard to conjure a vampire today without leaning on and into the peculiarities he lent the part, earning him fame, and saving then struggling studio Universal. Fun fact: a Spanish language version of Dracula was rediscovered and restored in 1992. Directed by George Melford, it was shot on the same sets, only at night with a different cast and crew.

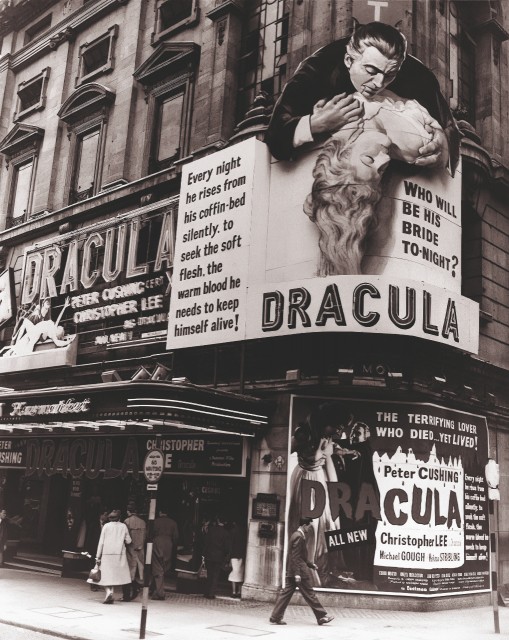

Dracula, 1958, Terrence Fisher

Retitled Horror of Dracula in the States to avoid confusion with Universal’s/Browning’s film of some decades earlier, for many an aficionado, Hammer’s version, which found Christopher Lee in the title role, simply is Dracula. It was the first time we’d seen the Count in colour; and, therefore, the first time we get to see red blood spilt (notably, being spattered onto Dracula’s coffin). For Frayling, following the “black-and-white years, British cinema had at last found a roundabout way of telling stories about sexual liberation”. With Lee’s seductive Count and Peter Cushing starring opposite as Van Helsing, Hammer’s venture was a huge success – to the extent that it spawned a brood of no less than eight sequels.

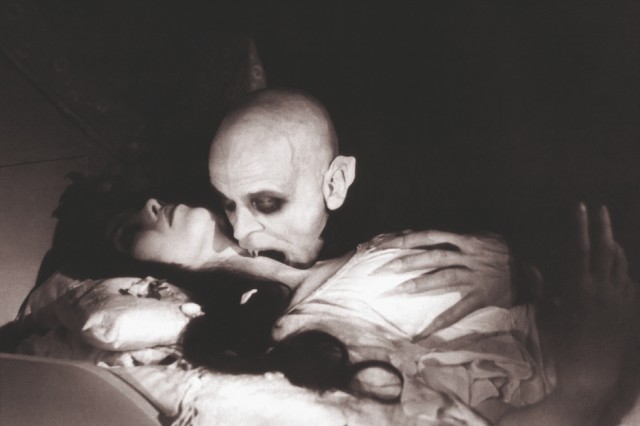

Nosferatu the Vampyre, 1978, Werner Herzog

In the wake of Hammer’s efforts, many an on-screen vampire lapsed into cliché. Largely kitsch and with few opportunities for heaving bosoms ready to be plundered by fangs left unexplored, in 1978 German New Wave director Werner Herzog returned to tap the copiously rich vein of the source. Starring long-time Herzog collaborator Klaus Kinski, heavily made-up in the lead, Isabelle Adjani and Bruno Ganz, it is described by Frayling as a “series of ‘impressions’” formed in response and in conversation with Murnau’s Nosferatu. He concludes that – while it was only given a limited release by Twentieth Century Fox – the reimagining was: “A beautiful, esoteric exercise.”

The Hunger, 1983, Tony Scott

By the latter stages of the twentieth century, the vampire and who might be one, was given increasing latitude. In Tony Scott’s 1983 film starring pretty things Catherine Deneuve and David Bowie as undead Miriam and her sometime lover John, as Frayling points out, there’s not a “castle or a peasant in sight”. Instead, The Hunger’s world is one of night clubs and polyamory. Kind of. Described by critic Roger Ebert as an “agonizingly bad vampire movie”, it nevertheless scores highly for opening in a club with perennial goth band Bauhaus playing Bela Lugosi’s Dead, and for its casting of Deneuve and Bowie. They are joined by Susan Sarandon, whose medical researcher tries to turn back the sands of time for a decaying John, while falling victim to Miriam’s charms.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 1992, Francis Ford Coppola

Seventy years after Murnau’s Nosferatu, Francis Ford Coppola turned his not inconsiderable talents to the mythology. But with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, “the biggest problem [was] you just can’t do it again”. This story is sweeping and more coherent than many other attempts. We learn about Vlad’s motivations – played with relish by Gary Oldman – his loss and his loves. Some of the cinematography, especially with its nods to vampire cinema history, is notable. It is, however, something of a curate’s egg. Failing to please Stoker purists for its romantic leanings, arguably the bigger crime was Keanu Reeves’ performance as Jonathan Harker which, says Frayling, “should have won the Dick Van Dyke Award” for worst English accent. Back in cinemas celebrating its thirtieth anniversary, you can judge for yourself.

Cronos, 1993, Guillermo del Toro

After the bells and whistles of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Mexican director Guillermo del Toro’s Cronos was a quieter affair. Much less a Hollywood figure then than now, GdT’s tale tinkered with the ideas pertaining to a vampire’s source of eternal life. There was also far less in the way of eroticism, which so regularly takes centre-stage in the genre. The love on show here is the purest kind, between a grandfather and grandson. An example of what can be achieved away from the expectations and conventions of Western cinema (i.e., Hollywood), if you haven’t seen Cronos but are a fan of vampires and del Toro, seek this out.

Interview with the Vampire, 1994, Neil Jordan

With Interview, we have the last great rendition of the elegant vampire about town to come out of Hollywood. Somehow, Tom Cruise is perfect as the cruelly seductive Lestat. His performance even satisfied Vampire Chronicles author Anne Rice, who had initially baulked at the prospect of seeing Cruise (whose previous roles included Top Gun, Days of Thunder and The Firm) in the role. He is joined (in somewhat leaden manner) by Brad Pitt as Louis – a vampire reluctant to embrace all that the role requires, and whose interview of the title is recounted. There are also notable performances from a twelve-year-old Kirsten Dunst as Claudia – saved from the plague and given as a gift by Lestat to Louis – resentful of being frozen in childhood, and Antonio Banderas’ Armand. A visual feast, Interview with the Vampire, remarks Frayling, delivers “a surprising amount of transgression”.

Let the Right One In, 2008, Tomas Alfredson

Increasingly, the best, most interesting vampire cinema isn’t being made in English. Let the Right One In (remade by Hammer in 2010 as Let Me In) sees Eli’s child vampire – reliant on a middle-aged companion collecting blood for her – striking up a protective, platonic relationship with bullied kid from a broken home, Oskar. Superb if grisly, it eschews many traditional vampire themes. Instead, it explores problems encountered by children the world over: vampire movie almost as kitchen sink drama. The film also poses the unsettling question: what keeps a middle-aged man killing for this little girl vampire? As a kind of pragmatic counter-point to Interview’s Claudia, when asked by Oskar “Are you old?”, Eli replies, somewhat matter-of-fact: “I’ve been twelve for a long time.”

Thirst, 2009, Park Chan-wook

Is there anything Park Chan-wook can’t do? Following the success of his so-called Vengeance Trilogy and outliers in his filmography such as I’m a Cyborg, But That’s OK, the master director turned his attention to the vampire (he would even name a subsequent, unrelated film, Stoker). Very loosely based on an 1867 novel by Émile Zola (Thérèse Raquin), in Thirst, PCW applies genre conventions to his fascination with human relationships, in particular the breaking of taboos. Here, Sang-hyun’s Catholic priest – who volunteers at a hospital, and is turned into a vampire following an experimental procedure gone wrong – falls for childhood friend Kang-woo’s wife. Thus ensues an exquisitely taught melodrama wrapped up in a vampire story that won the director the Jury Prize at Cannes.

Only Lovers Left Alive, 2013, Jim Jarmusch

Ranked in the top 100 films of the century so far and the fourth greatest of the 10s, Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive sees well-adjusted long distance relationship vampire couple Adam and Eve (played by Tom Hiddleston and Tilda Swinton, respectively) reunited. Reviews at the time of its release were at pains to point out the film’s superiority to the Twilight franchise, and although this cannot be disputed, the picture has more in common with Jarmusch’s conversation-heavy Coffee and Cigarettes than it does typical genre cinema. But it’s not all quiet rumination on high-brow and/or obscure culture, as the couple’s urbane reverie is disturbed by Eve’s unpredictable little sister, Ava (played with aplomb by Mia Wasikowska).

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014, Ana Lily Amirpour

For my money, the vampire film of the century so far, its director Ana Lily Amirpour has described A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night as an “Iranian Vampire Spaghetti Western”. Turning conventions about girls alone at night on their head, in a ghost town forebodingly named Bad City, it tells the tale of peculiar girl vampire navigating a world of drugs, prostitution and death. Like me, Amirpour was turned onto vampires via Anne Rice who, she has said, “was my first thing. I loved – addicted loved – all of that”. A vampire, she has also noted, is many things: “serial killer, a romantic, a historian, a drug addict.” A very contemporary take on the genre, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is the film I’ll be curling up with this Halloween.

Mike Pinnington

Vampire Cinema: The First One Hundred Years, by Christopher Frayling, is out now

Images: Christopher Frayling portrait; Nosferatu 1922 Count Orlok Max Shreck on the deck of the Empusa; Dracula 1931 original Style C poster; Nosferatu the vampyre 1979 mptvimages – all © mptvimages.com; stills: Bram Stoker’s Dracula; Let the Right One In; A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night