The Painter Who Changed My Mind: Helene Schjerfbeck

“My routine and by now automatic dismissal of portraiture was over.” Mike Pinnington on Helene Schjerfbeck, the painter that changed his mind…

In my late-ish teens, I bought a postcard reproduction of Francis Bacon’s Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake). Bacon had seen the mask at the National Portrait Gallery in London. Like his more famous and recognisable works, the floating in negative space visage channels the disturbing realism for which he remains so well known today. The postcard, however, which was Blu-tacked to a bookcase for years, said more about my just-beneath-the-surface tendency toward the gothic than it did any interest in figurative art – how it is made and what it can say about you, me, life, death, and the world.

I was (and largely continue to be) far more drawn to artists on or hovering around the abstraction spectrum. Peak modernists whose work was infused with innovation and better reflected the experience of modern life; Piet Mondrian, Joan Miró, Alexander Rodchenko – you know the kind of thing; all lines and primary colours. Not for me the staid – as I saw it – striving for pictorial representation. Especially portraiture. What’s the point in that, right? It’s boring. That’s what cameras are for (famously, coincidentally, Bacon often painted from photographs). Call it ignorance, snobbery, whatever – I had written off pre-modern artists, from Rembrandt to Paul Cézanne and everyone in-between. And so it remained. For a Very. Long. Time.

Flash forward to April 2017. I’m on a tour through Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum, home to Finland’s national art collection, which had recently debuted its Stories of Finnish Art exhibition. As you’d expect of a national institution, alongside homegrown talent, its holdings include globally renowned artists such as Edvard Munch and Le Corbusier. As much of a thrill as it always is to see the likes of Corbu in real life, though, it was work by an artist I’d never heard of (much less seen) that captivated me. Staring across the room, brilliant and contemplative, was a remarkable face. Momentarily forgetting my portraiture prejudice, I walked across the gallery to meet the painting’s stare, then quickly looked at the label on the wall, eager to know its author. It read, simply, Helene Schjerfbeck: Self-Portrait, Black Background (1915).

Suddenly and without warning, the walls came tumbling down: my routine and by now automatic dismissal of portraiture was over (it only took a couple of decades and a trip overseas). And it was due entirely to Helene Schjerfbeck. But who was she? On leaving the Ateneum, I was given the publication that went with the exhibition. Also titled Stories of Finnish Art, it is a book of essays and fictional reimaginings of some of the artists in the collection. Rifling through its pages, I was relieved to find Schjerfbeck had her own entry. Written by Sirpa Kähkönen, it situates the artist slightly adrift, caring for her elderly mother and questioning her ambition, her place in society and the world – but, happily, never her talent.

“I gave in to hope” begins one passage, reflecting on being cognisant of her abilities and where they might lead her from an early age. “I knew my eye, the precision of my hand, recognized the leap of mastery… I opened myself up to ateliers, dinners, outings, critics, loneliness, struggle.” The anxieties of a female artist, and what she felt she was allowed to achieve remained, decades later. “I manufacture joy” the fictional Helene continues. “My lines, my colors, my brushstrokes. And it isn’t seemly. It never was, and it isn’t now.”

The story, in-part bleak indictment of the predicament of and challenges faced by women artists, added flesh to the bones of my growing fascination with Schjerfbeck. Early last year (pre-lockdown), I made another trip to Helsinki. Scanning the city’s websites, I excitedly noted that my visit coincided with Through My Travels I Found Myself, an exhibition dedicated to her work (again, at the Ateneum). It was absolutely rammed, but this couldn’t dampen my experience of the show, which, including a plethora of paintings, drawings and sketchbooks, ranged from landscapes and still lifes, to depictions of some of the people in her life. Great though it was to see the breadth and variety in her work, most memorable was a set of sixteen self-portraits – what the critic Laura Cumming has called “one the greatest time-lapse sequences in European art”.

Made between 1884 and 1945, taken together they’re an incredible insight into a life; how the years can take their toll, not just physically, but also psychologically. Outlook, demeanour, the gaze, what she includes and what she omits, her palette; how her face becomes more and more like a studied mask as the years advance. But they also chart the development of the artist. From the, dare I say hum-drum classic realist examples of her early self-portraits, Schjerfbeck made a clear formal progression – no, let’s call it a leap – as she moved through the early decades of the twentieth century. Gone were the generous features and honey-coloured hair of her youth; these were replaced with confidently stylised angular lines, and pensive, almost distant expressions hinting at a rich and complex inner world.

Now undoubtedly the time of modernism, Schjerfbeck – despite her awareness of the strides made by first Cézanne, then Matisse and Picasso, et al – remained true to her own vision. She looked to Goya, Velázquez, Rococo painters like Jean-Antoine Watteau, and fashion magazines more so than to Cubism, Futurism or, later, De Stijl. For all that, she was never an artist out of time; she responded to and reconfigured her touchstones with a sensibility all her own. Indeed, in a letter to her friend Einar Reuter – a great admirer of her work who the artist went on to portray multiple times – she observed: “Let us avoid executing so precisely and exactly, that our work closes the way instead of opening it, let us imply.” It set her apart rather than adrift from the jostling pack. And, certainly, increasingly successful though she was by this stage, her painting never stagnated.

As life inevitably did its work, she responded – at times fearlessly. The self-portrait I had seen on my first visit to the Ateneum – with its rouged cheeks, hint of a smile and a jaunty paint-pot and brushes over her right shoulder – seemed imbued with a kind of hope and luminosity. An optimistic lightness of being that has surely triggered more than my own double take across the gallery. It was painted in 1915, the year Schjerfbeck first met Reuter. Altogether more disturbing, meanwhile, is 1921’s Unfinished Self-Portrait. In it, her face almost merges with the peasouper of a background, the hair is thin, dull, and barely perceptible, while deep scratches in the canvas across her eyes suggest a kind of self-harm. Tellingly, it was made in the years immediately following Reuter’s engagement to another woman, news that so shocked and disappointed Schjerfbeck, she spent three months convalescing in hospital. A tale of two portraits, of sliding doors, crossed wires, promise and regret.

The sixteen self-portraits in the exhibition gift us a record of a life as seen by its author: but also, so much more. There we can find all that has been visited upon her, both internally and externally. Alongside her relative solitude (she never married and, on her seventieth birthday, hid in a cottage away from her home to avoid unwanted fuss), she juggled caring for her mother with her profession. Besides this, her adult life took in the upheavals of a civil war, the Second World War, and an invasion by Russia. The churn of life, culture, death, and the world are all there, mixed in to and reflected in her work. None more so than in the paintings made in her later years. Racing against the cancer that ultimately killed her, between 1944 and 45, she made more than twenty self-portraits.

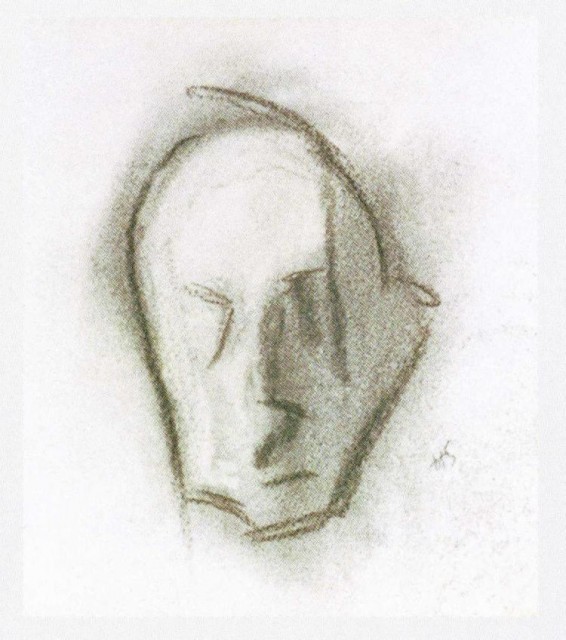

Addressing old age, Schjerfbeck unflinchingly cast herself as a kind of spectre in powerful works that are full of pathos. 1945’s An Old Painter, rendered in blacks, greys, a blob of pink, and blues, is chilling: more Nosferatu than human. Last Self-Portrait (c. 1945) sees a return to drawing, in charcoal on paper. With no eyes to speak of, and its waxy, almost post-mortem-like impression, it can only be read as a foreshadowing of her death; but it is also a kind of declaration: I’m still here. I was always here. Yes, me, Helene Schjerfbeck. She died in January 1946, aged 83, her easel beside the bed.

A decade later, her paintings were chosen to represent Finland at the Venice Biennale – testament to her ongoing appeal at home. Until very recently, though, the artist remained under-exposed abroad. This changed when Through My Travels I Found Myself was shown at London’s Royal Academy (before touring to Helsinki). In her review of the exhibition, the Observer’s Laura Cumming called Schjerfbeck’s “an art of peculiar beauty”. So peculiar, in fact, it reversed my long-held and committed indifference to an entire artistic genre. I give you Helene Schjerfbeck, the painter who changed my mind.

Mike Pinnington

Images, from top: Self-Portrait (1912), crop, Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery; Self-Portrait, Black Background (1915), Herman and Elisabeth Hallonblad Collection, Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery; Last Self-Portrait (c. 1945), Villa Gyllenberg, Helsinki. Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation