Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay – A Conversation with Jeff Young

“I think the city is a book and we can read it and re-read it.” Mike Pinnington spoke with author Jeff Young about his memoir, Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay, our philosophical attachment to place, and how memories can play tricks…

We think of ghost towns as places bereft of life, people and, often, hope. Indeed, when the Specials wrote their 1981 hit song, it was a lament at the rampant inner-city downturn they’d seen first-hand at that time. For author Jeff Young, though, whose latest book bears the same title, it is a reference first and foremost to the people and stories that imbue places with life (thus enriching ours), even after they’re gone. In turn, we carry them with us and, like Chinese Whispers, pass them on; they’re all about us, in the streets we’ve walked, the bars we’ve frequented and the living rooms we’ve grown up in.

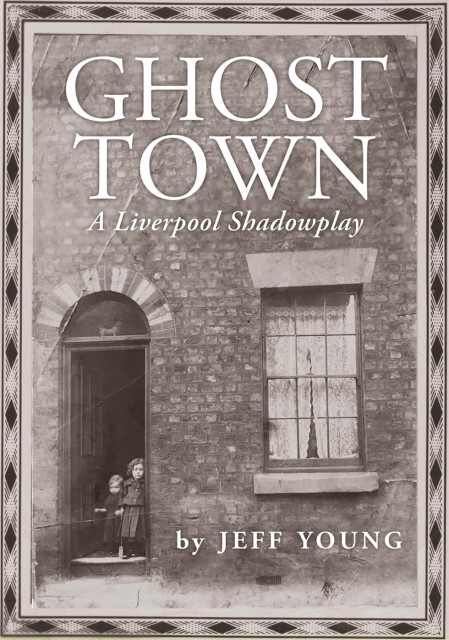

Recently nominated for Costa’s Biography Award, Young’s book – Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay – is variously autobiography, love letters to the city in which he was born (in 1957) and still lives, and intimate chat in the corner of the pub over a pint or two. “I quite like that it’s a book that nobody will know which shelf to put it on in the book shop… It’s a hybrid kind of book. It’s lots of different things – there is a history aspect to it, but it’s memoir and it’s a book of essays.” He is a warm and engaging conversationalist, a trait that comes through, seemingly effortlessly, in his writing. When I ask him what he was striving for, he explains that he was looking for a “confessional” voice, but also “tried to get on the page the way I speak, as close as I possibly could… as if we were in the pub, or going on a walk together and having a conversation. When you read it, I’m just telling you.”

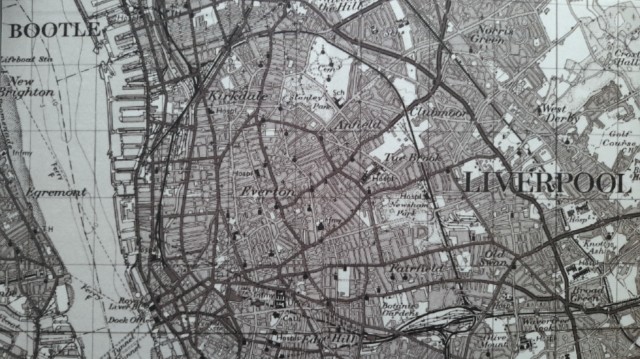

Liverpool as Memory

He was also trying to be honest about how we sometimes “fictionalise the past. I think there’s a way of, when we tell each other a story, to ourselves or to our friends over and over again, it becomes altered in some way.” The book is, he continues, “a bit of a struggle with memory, or an engagement with memory.” Between each of Ghost Town’s chapters is a photograph: of streets, people, paintings, sculpture, buildings, and books. What Young refers to as potent images “found on top of wardrobes and in shoe boxes.” They correspond, he says, “to that thing we were saying about memory. When you’ve got the photograph, you start to remember the content. And that slightly alters the memory that you had in your imagination.”

He uses, by way of an example, “a brilliant photograph of my granddad and my nanna. They’re both holding up bottles of beer and they’re thoroughly enjoying themselves. I never ever saw nanna and granddad drinking, but in that photograph, they’ve got bottles of beer!”

None of the photographs has a title, or a caption to explain context. “Part of the way the photographs are placed, they should be like when you buy a second-hand book, and something falls out of the pages. It might be an old postcard, or a photograph, or a pressed flower, or whatever. The way the images are placed in the book should feel like that.

“They’re deliberately not captioned. We just have to make up our own minds. I like the mystery of it. We wanted them to be ghosts and unexplained. When you read them in the context of the text, there’s a resonance to it.” It’s true, and as you hoover up Ghost Town’s pages, the images become portals as opposed to mysteries to be solved – through them, we access Young’s world, but also a kind of shared cultural archive, of old hairstyles, wallpapers, fashions and architecture.

Liverpool as Living Thing

In the book, he speaks of his “emotional – and philosophical – attachment” to Liverpool and, although he confesses to me to be “a bit nervous of the term psychogeography”, it deals with the specifics of place as much as it does people. Often, this is in reference to “places that have been treated carelessly and neglected. It’s not just an observation of what used to be there, you can feel the pain”, Young says. One such location is Lime Street which, he writes, he used to “think of … as a place made from films. It had three cinemas, and the movies spilled out of them, flooded the street and animated the pavements with mystery, desire and drama.”

For me, Lime Street is just the place you go to get the train. “There’s no way that the new Lime Street will ever possess memories,” he concurs. “It’s sterile. It’s an empty space now. People are never going to say ‘oh, we went to so and so’s on Lime Street on Saturday night’. It’s never gonna happen. That street can’t tell stories [anymore]. It’s been exorcised.”

Liverpool as a Conversation

It’s clear he feels a responsibility to Liverpool, one shared by all of its constituents. “I wanted the book to be – I don’t wanna use the word statement, but I can’t think of a different word. This is what this place means – it’s what it means to me right now, and what does it mean to you? What does it mean for the people who are reading it?” He situates Richard Wilson’s Turning the Place Over, a temporary work on the former Yates’ Wine Lodge at Cross Keys House, Moorfields, as a trigger for such questions. “I think that was one of the most remarkable conversations about the city. That artwork, it wasn’t just like a gimmicky event in the city. I think it was a conversation. ‘Look at it. Look at the fabric. What do places mean? What do buildings mean?’ I try and talk about that in the book as a starting point to have a conversation.

“It’s like saying ‘let’s have a pause’. That was a kind of a punctuation – a place to stop, a place to think. A place to look at a derelict building, a derelict building reimagined. And so, therefore, what does that inspire us to think about the rest of the city? That’s one of the most powerful interventions into the fabric of the city for years and years, I think.”

Liverpool as Novel

As our conversation progresses, it emerges that, for him, Liverpool – and by extension, all cities – are, in many ways, akin to books. “When you read a novel when you’re seventeen and then you read it again when you’re thirty or forty, or whatever, you find different things – in the white spaces between the ink, in the places where thought happens. I think cities are like that. I think the city is a book and we can read it and re-read it. Within the pages and within the words, the city has pages, and it has words, and it has chapters, I think.” In that case, I ask, what do you think the next chapters in Liverpool’s book will read like? His assessment, it’s fair to say, is that of a clear-eyed realist.

“Stories won’t be told about Liverpool One, and they won’t be told about Liverpool Waters, or going to the supermarket on Lime Street. Stories are told in places where communities gather, where people gather; to be with other people and to exchange ideas and thoughts and tales. What the city needs, if it’s gonna have any future chapters, is to maintain and to nurture those kinds of places.”

He bemoans the loss of grass roots, often maverick spaces (such as the Kazimier and Mello Mello), lost to land grabs and urban development, and highlights such gentrification as a risk to Liverpool’s ongoing story. “It’s really upsetting when you see independent venues closing, isn’t it? The thing that replaces the independent building is a diminishment of what was there, y’know? It’s just careless and thoughtless.”

He’s keen, though, to guard against rose-tinted nostalgia in and of itself. “New places are always going to be built and that’s good, but they need to have some kind of vision and integrity and take care of the people.” For Young, it starts with us, the people (and our ghosts, no doubt). “It’s not buildings that make a city, it’s the people and those people have to have a connection with place [for stories to continue to be told]”. His message, and it’s fair to say it’s a sound one, is: “Protect the stories.”

Mike Pinnington

Catch Jeff Young in conversation with Frank Cottrell-Boyce, Mon, 14 December, 7pm

Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay is available now in bookshops and via Little Toller Books