“There’s a panic in me.” The Big Interview: Don McCullin

Earlier this year, Don McCullin was given a career retrospective at Tate Britain. With the show coming to Liverpool, Mike Pinnington talks to the iconic photographer about his life’s work…

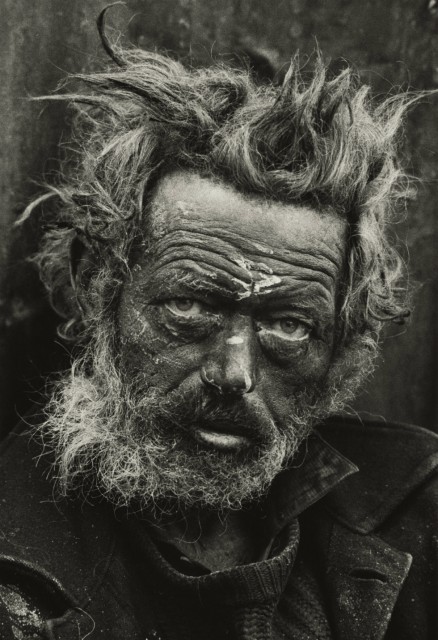

Searching, slightly lost, eyes loom out of a heavily lined face, caked in dirt, the unkempt hair and beard, signs of countless nights spent on the street; a man tosses a grenade in the direction of an unseen enemy in Vietnam; another is frozen, hands loose around his rifle, more prop than weapon – suffering from what used to be called shell shock, he stares off into the middle distance.

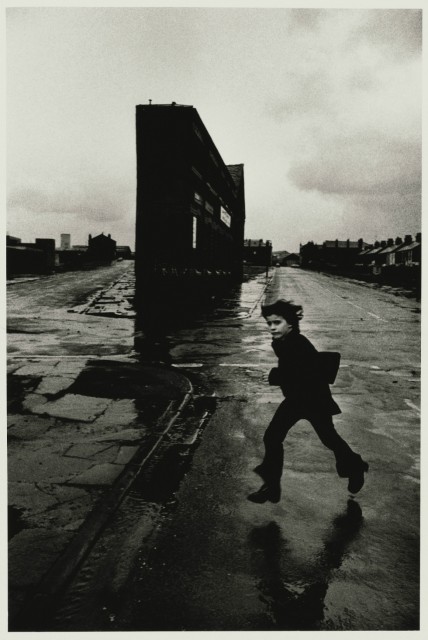

A boy, his pose not dissimilar to our grenade thrower, hurls debris found on waste ground in Liverpool 8, his friend curiously returning the gaze of the camera.

Don McCullin, over more than half a century, has made a career out of producing indelible images. Once you’ve seen his work, it tends to stay with you. The first image described above, that of a homeless man in late 1960s London, has remained seared into my mind. Indelible for all the wrong reasons, it attests to how deeply unforgiving life can be. In this and myriad other pictures, McCullin has reflected the times in which we live, told the stories of strangers on the other side of the world and shown us things we needed to see, hard as it might be to look.

Celebrated for his fearless and unflinching reportage, I jumped at the rare opportunity to speak to the iconic veteran photographer about his extraordinary career, the things he has seen and what keeps him going. We began, though, with the Tate Liverpool show that has just been announced for next summer. “I’m very pleased [about the show] … I’ve spent much of my enjoyable working photographic time photographing in the North of England and, you know, I think it’s time for me to give back really.” The show is touring from Tate Britain, and McCullin understands that not everyone can travel, even for garlanded exhibitions such as this. “Of course, it’s impossible for people who live two or three hundred miles away to come all the way down to London to see my exhibition – why should they?” he asks, pointedly.

The day before we speak, he’d been in Liverpool to meet with the exhibition’s curators to discuss how they might tailor it to the city, rather than simply replicate what has been done already. Having photographed the city earlier in his career, capturing the poverty, working-class life and a Liverpool almost unrecognisable today, can we expect to see photographs from this time included in the exhibition, I wonder.

“I’ve been looking at the work I did in Liverpool in the early ‘60s and the ‘70s, and it’s quite depressing to look at it. There was a big slum clearance programme, which made the landscape look like Dresden during the war. It’s almost a war-like scene photographically, so I’ve got some interesting pictures. And, you know, some of the people in my pictures were little five-year-old children in the streets up in Huskisson street and around that area, and now they will be grown up people with possibly grandchildren now, you know? So, I’ve documented a part of the Liverpool history.”

It’s fascinating to think that anyone you photographed then might come along and see themselves in these incredible photographs, I venture. “There won’t be more than a dozen [from that time in Liverpool], but from that dozen, if somebody recognises themselves from childhood in these pictures, I think they’ll be quite thrilled really.”

What has it been like, I ask, being back in the city? “It’s extraordinary when you look at these pictures now, because there are no cars in the streets – the streets are totally bereft of cars; it’s unthinkable today. Also, by the way, properties around there are so beautiful – people give their high teeth to live in places like that!”

While it’s true that the facades of those old town houses in Toxteth are beautiful, as somebody who has lived there, what lies behind them rarely fulfils the promise of the exterior. McCullin understands the irony in the fact those houses used to be inhabited by the city’s well off – and very well off – only for them to become part of what amounted to a ghettoization of communities. Was it important for him to show the conditions in which those people were living, I ask. And, on a practical level, how did they react to his being there?

“There was always a divide between the North and the South, and that created a great deal of suspicion, but I never had that feeling,” he says. “I would roam all over this country – and the other city I had strong connections with photographically was Bradford. They were both impoverished cities, and that’s what made me interested in them, because I didn’t think it was fair that the people in the North of England, who did all the hard work, the nasty work – y’know, why should they be forgotten and pushed aside? That was my interest – in coming to photograph the have and the have nots.”

This was no patronising mercy mission, with McCullin cast as saviour, however. Born into a working-class family in London, he himself grew up in poverty, and his photographs are motivated by an urge to report realities to those who might not otherwise seek them out. His is a career forged in not allowing people to look away – whatever the subject matter.

With the world every bit as much in turmoil now as then, what is it like to see his work in galleries and museums, when it was shot primarily as photojournalism? “I don’t have anywhere else to show [it]. If magazines and newspapers decline to show any interest in what’s going on in the world today – as they do – you know, you have television news which, once again, doesn’t really cover the world at large.”

Audibly annoyed, McCullin’s point is that “these institutions are run by monetary factors – if you wanna gather world news, you have to have people on the other side of the world working with you, and a lot of people, a lot of proprietors, are not actually engaging far enough and deep enough in the world news. So, you’re getting only a skimming. You look at your newspapers, you don’t really see any more real stories and features about the lives of others.”

It’s a pretty damning take, but equally, quite difficult to argue with. From this indictment on the state of things, I ask how he would find his subjects, back then, and what he makes of the photographs they led to. “I was always digging deep in places where people had no interest. But I had an interest in it because I was getting these extraordinary pictures, which have become more extraordinary – not because of me as a photographer, it’s time that’s made them extraordinary, because they become part of our history really.”

His modesty is matched by his generosity as, in the very next breath, he points out that “I’m not the only one who did it by the way, there’s two brilliant photographers, Graham Smith and Chris Killip, who come from the North of England, they did some great work.” Then, after a short pause: “It doesn’t need a Southerner to come up and trespass on somebody else’s territory, which they know better than me.”

Although passionate about social issues, McCullin is perhaps known best for his iconic war photography (which will, of course, also feature at Tate Liverpool). I ask him whether he views the results of shooting in a conflict zone differently to those made in the relative safety of towns and cities in the UK. “I see them [the photographs] all as war, actually, because social poverty is war, and it has to be stopped and it has to be addressed, you know. A lot of young people write to me and say ‘I want to be a war photographer’ and I say well, you don’t have to get on a plane and go to somebody else’s country, there are wars going on in this country – social wars and wars of poverty, and stuff like that, homeless people, all that’s a war in itself.”

Asked many times about how he deals with what he has witnessed as a photographer, here, he is equally pragmatic: “It’s all very depressing, I know that, but it’s something that’s probably always going to happen. There’s no shortage of material for a photographer.”

Presently working on landscapes – “I travel all over the place to do landscape” – he remains active in the field. Turning 84 later this year, I’m interested in what keeps him going. “My motivation is based on my love of photography,” he says. Acknowledging he’s not getting any younger, however, he continues: “I actually feel every day is a new challenge – and at my age, it’s a greater challenge than other people’s, because I don’t have time left on my side.”

And why landscape, why now? “Landscape is my last vested interest in my photographic life, because I live in it, and it’s also incredibly important because it’s under threat, you know?”

But, he says, “climbing up hills with my equipment is quite tough for me, and my feet have had it, my legs have had it, and I’m battling against the physical landscape itself against my physical self… My days are sometimes not long enough, but they’re too long for my energy to last, so I’m in a Catch-22 situation, really.”

Tentatively, I ask whether the age factor finds its way into his work. “Of course it does,” he replies forthrightly. “All my thoughts find [their] way into the work. My work is based on my thoughts and my moods and the way I perceive things, and how I consume these subjects in my thoughts, so, in the end there’s a huge deal of psychology that goes into what motivates my interest in the subjects I’m choosing to work with at the moment.”

All of which leads me to wonder whether or not McCullin sees photography as an artform, as many – including myself – do. “I see it as photography,” is the answer. He affirms this by saying that he feels “there’s no need to climb up to another level. You know, I use a camera, which has a piece of glass on the front of it, and I use the chemistry behind it, in the shape of the film and the emulsion.”

And, for him, here lies the key difference: “The materials are set in cement almost, whereas with art you can use any form of material you want; but in photography you’re obliged to use these bits and pieces, you know? That’s the way it is.

“I’ve never seen photography as an art form,” he continues. “I can see how some people would like to align it with art; we draw on the past from art, from paintings we’ve seen and the compositions of paintings, and other people’s work and that, but I mean; I’m gonna hold out on the art thing there, I strictly believe photography is photography, and it doesn’t need to be fancied up – do you know what I mean?”

The interview is coming to a close – McCullin is tired. He tells me he has a busy day ahead of him in London, having also travelled to and from Liverpool the day before. But I have to ask one final question: which photographers have informed McCullin’s career, and to whom he always returns. Enthusiasm takes hold. “There are many photographers – too many to mention – but Cartier-Bresson was an extraordinary man, and there was a man called Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Steichen. These early giants in photography were the people who inspired and drove me forward.”

But, it seems, it is in the doing, and the alchemical magic of the darkroom, that he is most captivated: “When you look at a negative, when you pull it out and you look at it, the excitement is so amazing and wonderful – it’s a thing that makes you wanna do it again and again and again and again, and I’ve been doing this for sixty years and I’m never bored with looking at a roll of film when I pull it out of the development – I still process my own film and make my own prints.”

As if to demonstrate this, McCullin tells me. “You know, I spend hours and hours in the darkroom, you will find all the prints at the exhibition will be made by me, and I have in my collection 10,000 prints I’ve made, and 60,000 negatives, so that alone tells you that I’ve not been an idle creature. Oh, and by the way, there’s 20,000 colour transferences to go with that if that’s not enough, and I’m making prints every week now.

“I’m in a hurry – time is not on my side. I’m 84 in October, so there’s a panic in me to kind of, you know, not put the icing on the cake, but to finish the cake itself.”

Mike Pinnington

Don McCullin is at Tate Liverpool 16 September 2020 – 9 May 2021

Images from top: Don McCullin in exhibition at Tate Britain © Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood); Don McCullin Liverpool 8 1961 Tate Purchased 2012 © Don McCullin; Don McCullin Homeless Irishman, Spitalfields, London 1970 Tate © Don McCullin; Don McCullin Liverpool 8 Neighbourhood, Liverpool circa 1970 © Don McCullin; Don McCullin Liverpool c. 1970 © Don McCullin