“I’m just one ginormous teaching sausage…” The Big Interview: Rosalie Schweiker

Sausage versus mince, tarot card tutorials, bra exchanges and Art Deliveroo: Esme Boggis talks to artist and educator Rosalie Schweiker about making art that doesn’t look like art…

I met Rosalie Schweiker outside Freemason’s Hall on Great Queen Street in Central London. We were on a Royal College of Art field trip; me the student, Rosalie the guide.

Notoriously closed-off, yet now overtly ‘open’, the Freemason’s Grand Lodge seemed a fitting start to a day exploring transparency and to think about Rosalie’s artistic practice. Much of her work exists as ephemeral events, meetings and conversations which interrupt social and political structures. Activation days, bra workshops and community art cafes act as spaces for collaboration. Jokes are made, exchanges had, skills shared.

After walking silently through the gold-cladded hall and soaking up a strange sense of secrecy, we headed to the Mayday Rooms – a social activism archive and meeting space. We talked as a group about the agency of public and private information in relation to our morning visit. Rosalie’s work confronts issues surrounding socially engaged practice through making art that doesn’t look like art. There’s no sense of a performed openness, it’s real yet intangible, navigating its way through an object infested art world.

As the conversation drew to a close, Rosalie and I relocated to a bench outside, with cups of 3pm caffeine to keep us going. Breathing in the fresh open air felt good. I turned the sound recorder on.

The Double Negative: I thought it would be interesting to start by discussing the humour in your practice. How do you see humour functioning in your work?

Rosalie Schweiker: This makes me sound really shallow but, ultimately, I want people to have a good time. I have this slogan – ‘people over art’ – I always prioritise the people over the artwork. When I started studying on a theatre course, it was all about this Marina Abramović thing of lying on an ice block for 24 hours and then that makes the art. I don’t believe in suffering in any shape or form, and art shouldn’t contribute to that. I just can’t deal with this sort of seriousness and pretentiousness in the art world, and I know that sometimes makes me really anti-intellectual and ignorant and rude, but I just can’t deal with it. I’m not strictly pro-humour, but I just think it’s not really that serious.

I feel that humour can sometimes be seen as frivolous, but it acts as a great access point.

It’s also a nice way of getting criticality into the work, especially around yourself and your own position. If you’re able to make a joke about your own artwork, that’s a good thing.

I was reading about your projects, Hanging Low and UU Bra Exchange, and was wondering if you could talk a bit more about the reasoning behind using boobs and bras as subject matter?

In 2016, I was in a bra shop. I think it was Bravissimo or somewhere that was supposed to be for plus sizes, or whatever you want to call it, and I just couldn’t fit into anything. I just stood there, trying to get this fucking thing shut and thought this is exactly how I feel about the art world. Trying to get this thing on, to make my boobs not look like they have any gravity in them, that they’re these weightless things that I effortlessly carry around. The sales assistant was apologising to me and I was apologising to her and we both felt awful.

A week later, I got an e-mail from a curator in Germany, Juliane Schickedanz, who was asking me to do a solo show at the institution she had been interning at. I’d obviously been thinking a lot about bras and thought it would be amazing for the show. We set up the exhibition space as a show room so people could try them on in really big comfortable changing rooms [resulting in »DD+« exhibition at the Bielefelder Kunstverein].

There’s something really interesting about changing rooms and how you feel when you’re in that space. The lights, the mirrors, scrutinising your body – you know that people are probably feeling exactly the same in the next cubicle.

Yeah, and we had tea and coffee, and loads of space so you could go in to the changing rooms with other people. Alongside the show, there was an extensive events programme – meeting with psychologists, surgeons – and I was also working with Leonie Cronin, an artist and yoga teacher. We talked about how when I do a down dog, I’m basically suffocating myself because my boobs are in the way. So it’s about humour again, and what happens if your body doesn’t fit into these practices that are meant to be relaxing.

I always do this thing when I have to give a lecture and stand behind a lectern: I just lift my boobs up and put them on the lectern and say ‘ahhh, that’s more comfortable’ and then everybody laughs. I’m making that joke because I feel really vulnerable and insecure about my body. It’s not that my work is self-help either, it’s just about how you use the skills that you have as an artist to impact on systems that exist outside of the art world. I was trying to find a form for how art could be a mediator between these two different things, and then Brexit happened, and I was doing politics for a year and a half.

That was when we first met wasn’t it? When you came to teach at School of the Damned. The posters you made for Britain is not an Island were incredible. I was posting them all around Bristol and I bought them to Wales just before the referendum vote –

That’s dangerous.

I know. I kept making my (then) boyfriend stop his car so I could stick them on the Vote Leave signs. Could you talk a bit about the project, Britain is not an Island, and how it’s progressed and evolved into other political projects?

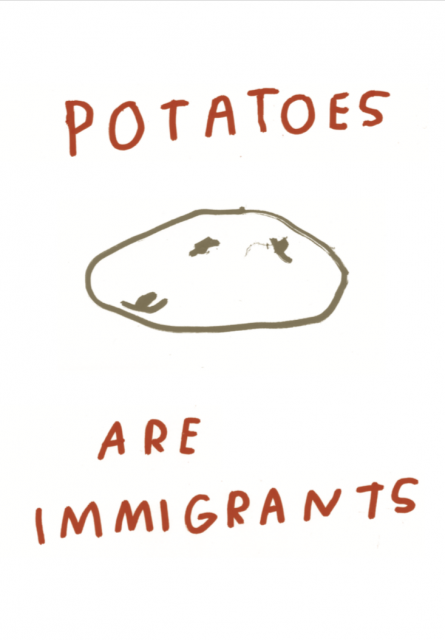

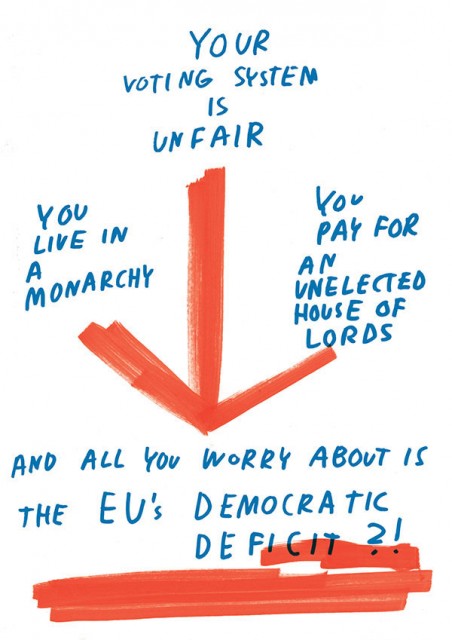

Yeah, so this project was never really supposed to be anything, but the remain campaign was really shit. It was pretty clear to me that it was going to be leave right from the start. I had this huge amount of existential fear and panic and a feeling that I had to do something. I met up with artist, Kathrin Böhm, and Mia Frostner, a graphic designer, and we decided just to make some funny slogans. It started as a few posters, and then grew into a campaign called Keep it Complex.

After the referendum, we did some crowdfunding so we could hold activation days. We did a whole weekend in different venues trying to bring people together to kind of speed date them, to say here’s a politician, here’s an artist, here’s a designer – just trying to form a space where people could create an infrastructure through mutual interests. Keep it Complex is now run by five women. It’s not funded, it’s quite unstructured, it’s quite informal, there’s lots of things wrong with it, but it’s a group of people that just want to do something. It’s about having a focus point of somehow being present with politics in the arts, as artists, as cultural workers.

It seems really responsive to whatever may be happening politically.

Yeah, there’s not the capacity in the group to be doing stuff like policy setting. There’re other groups who do that so much better – it’s much more about using the skills of designers or art people to do something. It has its up and downs, but it’s a good vehicle for meeting other people who are involved in politics.

Going back to the posters, it was so refreshing to see a different political aesthetic.

That’s the genius of Mia the Graphic Designer. I drew some stuff and asked her to turn it into graphic design. She said we should leave it as was with the handwriting. It’s really different because you don’t get those aesthetics in Leftish politics. Leftish politics aesthetics always have the too small type font, red and black, and nobody can really see what it’s about.

Would you say your work is a form of activism?

I can see why it would be seen as that, but I don’t identify as an activist. It’s the word that I find difficult. I think a lot of the activism I do is actually not doing things, so what’s the word for that? Pacifism? I think it’s more about what you choose not to engage with, so for me to not want to have an exhibition practice, that’s an activism, but it’s not visible as activism because it means that I’m just not visible. For two years now, I haven’t been flying, so whenever I get invited abroad, it means I have to do much more work here than I used to. That’s the small stuff which nobody really knows and that can be activism, but I don’t really have an agenda.

I was playing devil’s advocate a bit there.

It’s a good question. I just don’t really know.

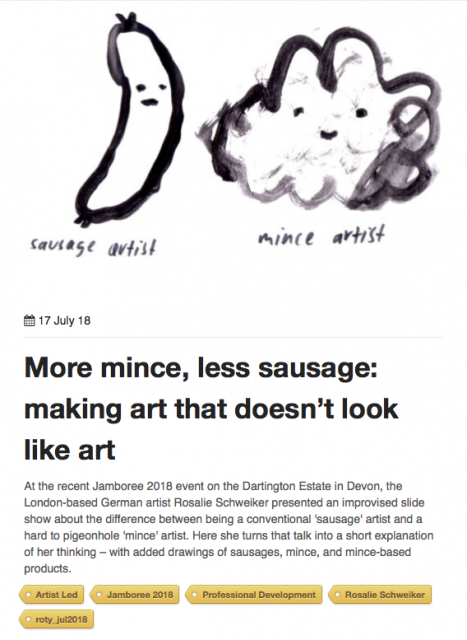

At what point did you realise you were a hard-to-describe ‘mince artist’? [As explained in Rosalie's popular article for a-n, as being the opposite of 'sausage artists', who 'make easily recognisable, tasty art sausages, like solo shows or performances from 6.15 to 7.30pm on a Friday evening'] As someone who didn’t want to contribute more objects to an already object-saturated art world?

I do enjoy objects, and my partner would probably say that I’m an object fascist because I really control what goes into our flat. I can spend two hours making a flower arrangement, and finding different little papier-mâché sculptures to put with it, which feels a bit 1950s housewife. It’s only been the last three years that my life has been in one flat, with actually earning money in some capacity. Before that, I was living out of a suitcase most of the time so making objects was never really something to consider. I also just don’t find exhibitions that interesting to make – it’s such a stress. You’re in the studio, and then you’re worrying, and then you have this private view, and then you have this thing that you made, and then everybody looks at it. That’s a completely different art world and I realise how far away I am from that.

I do still contribute objects because I make paper publications which are completely useless, and I’m constantly thinking why I’m not doing this online, because what kind of lunatic sits there in 2019 and photocopies fifty publications which takes them six hours and then two people see it. But I do get such an immense pleasure out of sitting there with scissors and glue and pens and making a publication.

I really wanted to ask you about the interview on the home page of your website, which talks about being a DIY or low-fi artist and people thinking it’s because you have no other choice, but, in fact, you’re consciously deciding to work in this way.

There’s always a question of whether it’s a mistake or not, and maybe it’s both. But I’m 33 now, and if I wanted to learn Photoshop I probably would have learnt it by now, wouldn’t I? The fact that I haven’t maybe means that I’m not ever going to do it. I don’t know, maybe I will. Every year I write it on my New Year’s resolution list.

Mine’s always InDesign…

Yeah, InDesign. It would be great if I could do that, but it’s more about accepting your limitations, I’m really pro-that. I recently went to this Sister Corita Kent exhibition which showed these massive screen prints, and after I left I was like ‘I wanna screenprint’. When I see really good art, it activates me. And most of the time it’s stuff that I feel is somehow possible for me to make, it’s not out of reach. If I see a Jeff Koons ginormous balloon thing, there’s no way in hell I’m ever going to produce that, so it just leaves me cold. It’s a different kind of artist isn’t it? It’s important to do that thing you connect with, and then if you connect with it, others will as well in a way that’s –

Because then there’s a sincerity in it?

Yeah, or just a practicality. Most people can’t be full time artists and maybe nobody should be. If we can’t incorporate it into our daily lives, then what’s the use of it? This outlook does make my work feel really bitty a lot of time. At the moment, I’m doing so many lectures and workshops and I just can feel myself becoming a person that I don’t want to be. You just talk so much and become so sure of your opinions, and if you do the job well you do need to educate people. It sounds very esoteric of me, but you lose that ability to listen because you’re constantly on this adrenaline. It feels like I’m talking out of my arse and that’s not a way to live your life. There should just be more non-verbal teaching, and I’ve managed to do it sometimes but at the moment it’s not really happening.

By non-verbal do you mean activity-based learning?

Yeah, just doing stuff. That was the idea with the field trip today.

How long have you been doing tarot card readings?

For a long time. I don’t do them as much now as I’m teaching a lot more, but it’s a good little side hustle. I found myself having loads of conversations with people then not being able to charge them for it, so if you read tarot, it’s basically charging for a tutorial and you get to have really interesting chats with people. It’s a way to have a social practice and a product. I’ve also taught loads of other artists and other people so it’s something that’s shareable in an easy way.

Tarot reading seems really useful, utilising conversations with others. It really comes back to the whole thing about artists, especially artists working with social engagement, having to find different ways to sustain themselves. It’s turning a conversation into work.

It is work. I was in Blackpool at the time, working on a different project, and there was an amazing tarot card reader in the indoor market and she charged £5. The tarot cards that I use were drawn together with Jo Waterhouse, so they’re not really proper tarot cards, they’ve got nothing to do with actual tarot. I find card reading very similar to the skills that you have when you’re a teacher or when you’re doing social practice. You’re training yourself up to read humans better.

I was looking at your Instagram the other day and saw a note that you have stuck to your computer of Yes’s and No’s for 2019 – what’s an Art Deliveroo workshop?

I’ve been doing these terms and conditions for a few years, I can’t really enforce them, but I still do it. This one came out of a few occasions at the end of last year when, for example, I went up to Manchester for a workshop with a gallery and nobody came and it felt so shallow. Some galleries don’t really care what you do, just that something happens.

So, this is the Deliveroo thing. I feel like I’m driving around on my bicycle and I’ve got a complete workshop on my back. I can just turn up, do two hours and we have a good time and then I go again, but there’s no engagement. The institution outsources their social engagement to me, they don’t have to take anything on board which is developed. It’s just like you’re an absolute zero hours, easily bookable, no economic security worker which is what Deliveroo drivers do. It’s really not fulfilling. For me it’s just a phrase that describes this workshop culture.

Although, I was doing this one with South London Gallery which was amazing. I worked with these kids for just over half a year, we talked, they criticised me, I criticised them. There’s feedback.

You’ve actually had the time to establish a relationship.

Yeah, I know their names! That’s major.

And that’s where that real long-term engagement comes from, not a kind of drop-in drop-out, organisations filling a gap. What ratio of mince to sausage are you feeling right now?

I feel like I’m just one ginormous teaching sausage. That a-n article was so interesting because I would never have thought about publishing it myself. I did it as a presentation at Jamboree [artist-led festival] because it was my go-to, five minute talk. You know how you have your repertoire of jokes that you make in your profession because you know that joke works – it was one of them. I’ve had so many emails about this article from, I’d say, 99.9% women of a certain age who really identify with this shit. I’m happy that I provided a metaphor that you can use to justify what you’re doing, but I’m also scared that this seems to be such a structural issue. There’re very few men who understand what it’s about and women, you just say it, and you don’t need to explain it, they just feel it.

That article spoke so many truths for me, yet it’s so playful. So many artists don’t say what it’s actually like, or just don’t engage with those questions.

I think the one major skill I have is not knowing that I should be afraid of this. It comes with my practice not being formed in the traditional way. Why would you be afraid to say what you feel? So much in the art world is about saving face and pretending to know what you’re doing through a smokescreen of bullshit. Nobody really knows what they’re doing.

I saw my friend San Keller give a lecture recently and one of the students asked him in the Q&A what art means to him. He was just like: ‘It’s my job.’ I just thought, you’re a fucking genius. With all the drawbacks, with all the pleasure of it, it is a job. Art isn’t part of my identity and now I find that easy to say. You do have this weird kind of freedom with being an artist, but it comes with basically having no effect. If you really cared about politics then you would put yourself up for an election, but as an artist, you are constantly hovering. I really don’t believe in art as this thing which is going to save the world.

Esme Boggis

Feature image photo credit: Sophie Mallet

All other images courtesy Rosalie Schweiker