Slow Violence: Madiha Aijaz at

Nelson Library

Amid government cuts and ambivalence, Jacob Bolton finds hope and the means to keep public spaces alive in a new presentation of Madiha Aijaz’s work…

Nelson library is busy. At the computers there are tradespeople hunting cheap tools off eBay, students feeling the weight of the Friday afternoon, mums navigating universal credit mazes. Their kids play between the aisles of books, hundreds of which are in Urdu and Polish. There’s a group of women knitting in a side-room, and a display for children’s events coming up that month. It’s animated, is what I’m saying – public space getting well-used.

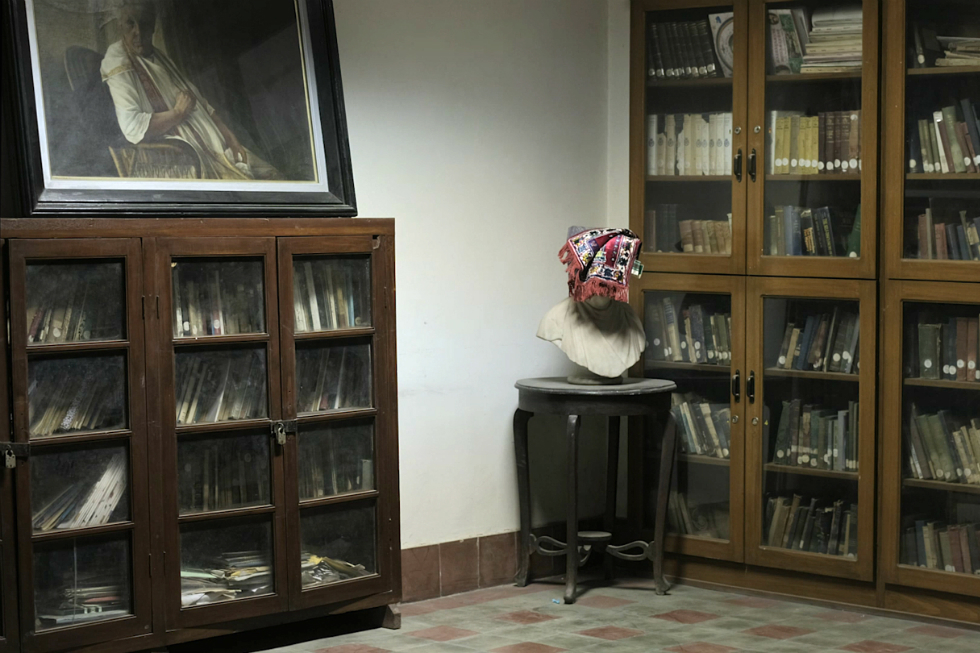

Also here, scattered throughout the building, are Madiha Aijaz’s photos and films. They were selected by In-Situ, and Mums 2 Mums, a parent’s network based in Nelson who between them share a vast number of languages, the area’s linguistic richness nourished by years upon years of migration during Lancashire’s explosive industrialisation. One wall of the library is lined with The Librarians: low-lit portraits of linguists of dying languages. They are photographed in their space, at ease, commanding the air around them, yet there’s also a sense of defeat, of the photo being not just a portrait but an act carried out in preparation of a memoriam: they are embodied knowledge, and when they go so will the keys to unlock the poetry traditions they have dedicated their lives to. A short film upstairs (nestled next to the microfilm archives and books on the witch trials of nearby Pendle) looks at the theosophical society in decline, cut with shots of children pouring into a school, making new knowledge, their own language.

The centrepiece, These Silences Are All The Words (2017–18), is comprised of librarians’ conversations: they chat about who is coming into the library later that day, they mistranslate and laugh about it, they lament the slow death of their languages and how Urdu TV presenters are beginning to use the English phrase ‘viewers’, mispronounced as ‘weavers’. The shots are long, reflective and enchanting – dust passing through sunbeams falling onto piles of books, the view of the traffic through a window, a plant taking root in the cracked concrete outside.

The violence of colonialism and postcolonialism comes both fast and slow. The fast violence is that of displacement, occupation and destabilisation, and it’s the more visible of the two. Infamously, Karachi is no stranger to it: following the partition in 1948, in which British India was split into India and Pakistan, the city became a major site of conflict. Waves of unrest followed, including the 1972 language riots (which some date as the start of Karachi’s ‘Three Decades of Violence’), in which the Urdu-speaking population was left alienated and angry following a government bill to establish Sindhi as the sole official language of the province. Words, and people’s right to use them, cut deep in Karachi.

The slower kind of violence is the long-term systemic violence of negating a culture, eroding a language, neglecting civic and social infrastructure to let it stagnate and fall apart. “There is no town planning”, one of the librarians remarks on Karachi’s rapid construction after years of unrest, “burgeoning cities lose their sense of humanity”. This kind of violence is very difficult to see. Aijaz manages to show it though, through looking at what is missing, what is becoming empty, unused, neglected – the cracks in the concrete, the rooms full of books with the lights left switched off, the fading health of the librarians carrying languages that are dwindling with them.

Aijaz’s work demonstrates that the starvation of sites of public knowledge amounts to state violence. This slow violence can also be seen in the UK right now, with libraries left to rot under austerity. In 2016 Lancashire County Council announced it would close 20 of its 73 branches. Last year the library budget was cut by a further 10%, double the national average. Councils are obliged to provide a baseline library service, yet no funding is ring-fenced for them. A 30,000-strong petition to allocate dedicated funding was rejected last year, on the basis of “giving greater funding flexibility to local authorities”, in which “flexibility” translates to offloading the accountability of cuts to desperately strapped councils. What’s at stake here, and what Aijaz’s work really gets at, is the ongoing loss of public space and the loss of public knowledge, knowledge as commons, a civic fabric that we are all, incidentally, both ‘weavers’ and ‘viewers’ of.

Situating the work in Nelson library acts as a quiet protest against these brutal cuts, a calm but firm call to use public spaces, keep them alive. The shots of the dust in the libraries falling into neglect feel almost prophetic here, showing what may become of the space if it doesn’t survive. Maybe it’s the silence of these scenes that gave the work its title, the only ‘words’ that can carry the quiet devastation of willful decay, the slow violence of disinvestment.

We won’t ever know for sure: earlier this year, Madiha suffered a cardiac arrest, aged 38. It was unexpected. In 2018, we had spent a couple days together walking around in the sun in Liverpool after working on the installation of her work at Open Eye Gallery, and we kept in touch. For what it’s worth, I want to share that she was a truly wonderful person, who cared a great deal, and who always had the right words.

Jacob Bolton

Jacob saw Madiha Aijaz presented by In-Situ at Nelson Library as part of the Liverpool Biennial Touring Programme

Images, from top: Madiha Aijaz: Memorial for the Lost Pages (film still, 2018); These Silences Are All The Words (2017–18)