“Art schools remind us of what powerful civic aspiration looks like”

“Research and practice, history and memory, urban space and politics”: John Beck and Matthew Cornford outline the initiating factors, aims, influences and processes that went in to their current Bluecoat exhibition, The Art Schools of North West England…

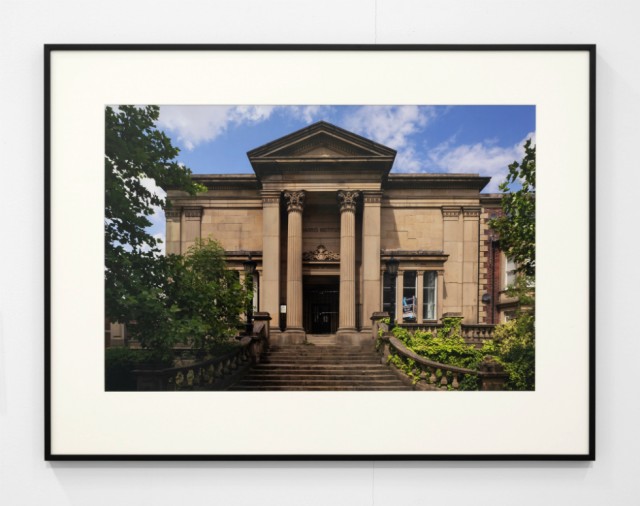

John Beck and Matthew Cornford started tracking down and photographing the sites of British art schools a few years ago, prompted by the discovery that the college they both attended back in the early 1980s was disused and up for sale. What started as a relatively unorganised assessment of where art schools used to be and what happened to them has turned into a determined project to document all of them. Their most recent work is currently on show at Bluecoat in Liverpool.

John Beck: In the 1960s there were over 150 art schools in England alone and the idea of ‘art school’ was commonplace enough for the term to signify not just a place of study but an almost subcultural set of attitudes and practices. Most of the art schools, many of which were built to meet the needs of industry in the 19th century but which became, through various economic and sociological transformations, increasingly out of step with educational policy, have been amalgamated into larger institutions, repurposed, abandoned, and in some cases, demolished.

Seeking out the sites of art schools is partly a simple act of retrieval – unlike more famous schools or universities, there is no readily available coherent and consistent account that tells the story of all the British art schools and how they were used. Aside from this cataloguing process, though, the gathering of information and the photographs of the sites has become a multifaceted form of investigation into a number of related areas, all of which are linked by the presence of the art school building (or its absence).

Finding the art school has involved an exploration of the towns and cities in which they are situated, and the current use of the site has often spoken directly about where we are now. Sometimes the old buildings are in gentrified (or optimistically wannabe gentrified) parts of town, repurposed as the ubiquitous luxury flats. More often, they are in sometimes massively under-resourced and commercially abandoned town centres, part of the sold off or closed down civic infrastructure in towns that once thought having a local art school was a good idea (and good business).

So, the bigger narrative includes urban planning (or not planning), education policy, patterns of de-industrialisation, ‘redevelopment’, property speculation and revanchist raids on public space, and the place of the arts in society. Are the art schools heritage, history, resources or ruins? Are they just bits of an old order that is no longer relevant, or are they markers of a lost utopian moment where state-funded arts education could take root and help shape towns and cities all over the country? Were they dreary training colleges for factory fodder or a means of escape for the aspirational but educationally challenged working class? The responses will differ depending on where and when the focus is placed, but the reason for wanting to document the whole lot of art schools is to try and get to the bottom of some of these questions.

Although we didn’t design the project in this way, the opportunity to produce an exhibition in Liverpool allowed us to focus on one of the most important art school regions. As the epicentre of the first industrial revolution, the North West generated the wealth to build art schools and the workforce to be trained in them. Many of the art and technical schools were grand, arrogant cathedrals to industry and capture something of the strange spirit of the times – an outgrowth of both working class aspiration and business class confidence. A recent book by James Moore, on art institutions in Lancashire during the long nineteenth century, High Culture and Tall Chimneys, tells the story in some detail and helped sharpen our understanding of how it all started.

Matthew Cornford: The core of the project is photographing the sites. In terms of the form of the images – size, format, composition, style, colour or black and white – I don’t recall looking at any one artist or photographer or genre in advance of beginning the art school project. The very first photograph of a former art school building I took was Great Yarmouth College of Art and Design, which I visited in Spring 2009. This was the art school John and I went to back in the 1980s and at that point there was little sense that this would turn into a larger project. The photographs are all shot on 35mm film, with a hand-held camera fitted with a 50mm lens. The first series, which become the basis for our article The Art School in Ruins (2012), were all shot on a small lightweight digital camera set to auto with an autofocus zoom lens. The distorted perspective on the buildings was subsequently corrected in Photoshop.

Following the interest in our book, The Art School and the Culture Shed (2014) and the offer from the Bluecoat of a solo exhibition, I thought more seriously about the technical and formal aspects of the photographs. The decisions that lead to the framed work in the exhibition are complex and based on a number of practical and formal considerations. I have inevitably drawn on my past experience working with David Cross (as Cornford & Cross) in producing photographs of our site-specific installations, a number of which were architectural in scale, outdoors and often rooted in specific regional contexts, works such as New Holland (1997) Jerusalem (1999), and Utopia (1999).

In terms of influences, I am familiar with the Düsseldorf School – Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Thomas Demand – but apart from the early street photographs by Thomas Struth I don’t feel much affinity or connect with their various projects (or the scale on which they can afford to produce the work!) which seem to be focused on questions about photography itself. More usefully, I was very familiar with of a number of artists associated with conceptual art who’d made work based on photographs of buildings. There seemed to be two approaches, firstly the (apparently) amateur or ‘disinterested’ photographer, photographs taken without specialist equipment often from street level and without much compositional consideration, for example Hans Haacke’s famous work on slum lords and the art world, Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971.

Secondly, artists producing photographs of a quality akin to professional commercial practitioners but uninterested in the expressive or established pictographic aspects of the medium, such as Ed Ruscha in his small books, like Thirty-Four Parking Lots in Los Angeles (1967), or Bernd and Hiller Becher, whose ‘new objectivity’ series of industrial archetypes are now part of the conceptual art canon. I was also aware of the New Topographics photographers – Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Nicholas Nixon, Stephen Shore and the Bechers, among others. All of these worked in black and white, except Stephen Shore, whose images often included atmospheric blue skies with plenty of clouds. I’d add to this list Aaron Siskind, best known as an abstract photographer, but who undertook a project to document every building designed by the architect Louis H. Sullivan. I came across a book on this project by chance in a bookshop closing down sale. Siskind included details of some of Sullivan’s buildings in his survey, something we decided to do with the art school project.

My aim for the Bluecoat (and other future shows) is to produce photographs that are matter of fact and straightforward, but that have enough presence to hold the viewer’s attention in the gallery space in terms of size and image quality. To achieve this I needed to learn more about architectural photography and learn how to use prime tilt-shift lenses, lenses that allow the photographer to control the perspective in-camera, removing or minimising the distortion you commonly see with photographs of buildings. This also meant an upgrade in photographic equipment and a steep learning curve in terms of my technical ability – a curve I’m still on.

After pondering the pros and cons of using a large-format film camera, I decided the technical challenges of the locations I’d be working in, busy town centres with lots of traffic, people walking by and narrow spaces between buildings, would make this option impractical and far too expensive. So, I’ve effectively duplicated/adopted the kit used by professional architectural photographers: sturdy tripod, full frame professional digital SLR camera, range of tilt/shift and zoom lenses and cable release. I also decided that the photographs would be shot in colour rather than black and white. Black and white seemed too nostalgic, too readily associated with the ‘stark austerity’ of the topographic school, 70s conceptual art and the darkroom.

With the Bluecoat show, I also started to look and think more consciously about making the images into a series, and whilst I have no say in the location or indeed what the type of building or site I’m going to photograph – it could be anything from a late Victorian Grade II listed civic palace to a carpark or modern housing estate – I could decide on what to exclude. As the focus of the project is the site or building, I aimed to exclude anything that would detract from this: cars, lorries, people, temporary hoardings, rubbish bags, banners, scaffolding, etc. This proved to be rather more difficult in reality, with some buildings needing to be revisited several times due to parked cars or scaffolding being in the way. The other key element was the weather and direction of sun light, I’d aimed to take most of the images during the summer months when I was away from teaching, which meant I had longer hours of daylight and general good weather, but looking for the optimum time of day for the shot was another factor in having to revisit a number of sites.

JB: The removal of the extraneous is intriguing because it seems like a flagrant break with the kind of documentary integrity that you might expect a project like this to defend – if you are determined to photograph the art school site whatever is there today, then surely you ought to photograph whatever is in front of the camera and not leave things out. That would make this about photography, though, and about those debates surrounding the ontological claims of the photograph’s indexicality. Despite the fact that photographers have always altered images before, during and after the picture is taken, the ethical commitment to the truth-telling capacity of the photographic image remains powerful and does, I would argue, need defending (though not here).

On the other hand, this is not really a project about photography as such, though it is important that each site is visited and photographed. It seems important that the photograph is the outcome of a process of research (finding the site) and of physical investigation – getting there, wandering around, finding a vantage point. The act of avoiding or removing signs of vehicles, people, and so on, does, though, make the photographs more than dumb records produced by a recording device and repositions them as compositions.

For me, anyway, the project allows for an ongoing conversation across a number of different concerns. These would include the function and usefulness of photography as a means of gathering information and identifying differences and similarities across times and spaces, but also, more generally, about the relation between research and practice, history and memory, urban space and politics. Laying out a series of images of art school buildings (mostly repurposed) and finding out what happened to those institutions also involves thinking about changing attitudes toward education and who pays for it; what the role of public buildings might be in town centres (indeed, what the role a town centre might be); how art and education have always been entwined with the economic fortunes and social aspirations of towns and cities.

The grand art school buildings of the North West also remind us of what powerful civic aspiration looks like. The art schools of the region were undoubtedly built to serve industry by providing trained workers, but they were also fuelled by the collectivist ambitions of the organised working class and sat side by side with other civic architecture – town halls, libraries, museums and galleries – intended to embody the cultural values as well as economic power of the town. Sure, there is a Foucauldian dimension to this, whereby imposing cultural institutions can be seen to inculcate bourgeois expectations of decorum and deference, but there is also room, we think, for a more emancipatory dimension to be given space. Reflecting on the past need not just be about a conservative mourning for what has been lost; it can also be a way of reflecting on what is – indeed, what has already been – possible. An art school in every town – what an absurd idea. And yet, there they are.

John Beck and Matthew Cornford’s exhibition The Art Schools of North West England continues at the Bluecoat until Sunday, 31 March. This Saturday they introduce discussion What Was Art School? (Bluecoat, 1-4pm), which seeks to explore the legacy and importance of art schools in British cultural life.

Main image, courtesy Rob Battersby