“Now people realise that there are not only white artists…” The Big Interview: Rasheed Araeen

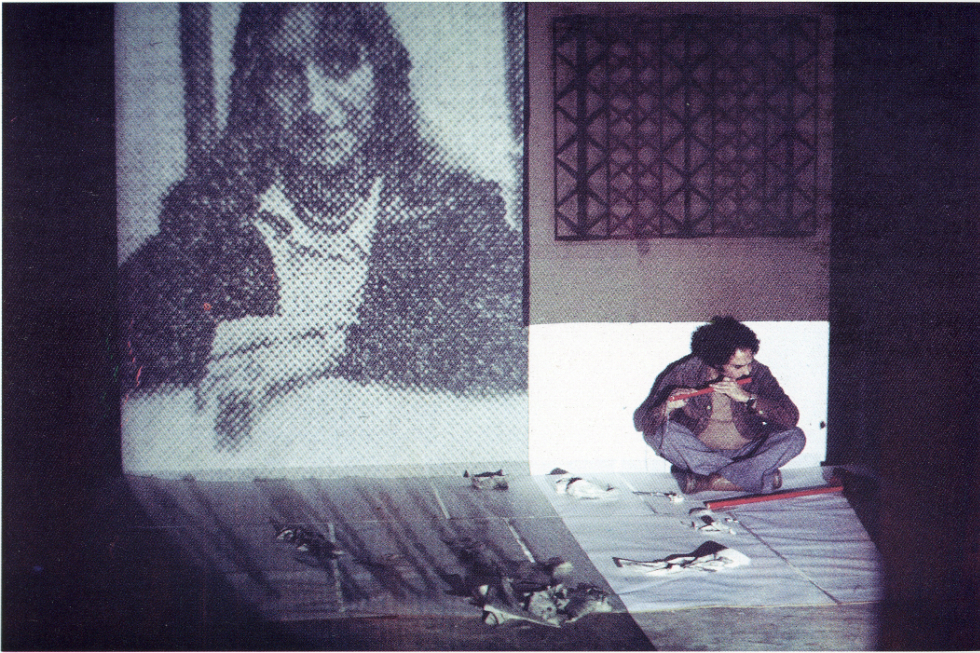

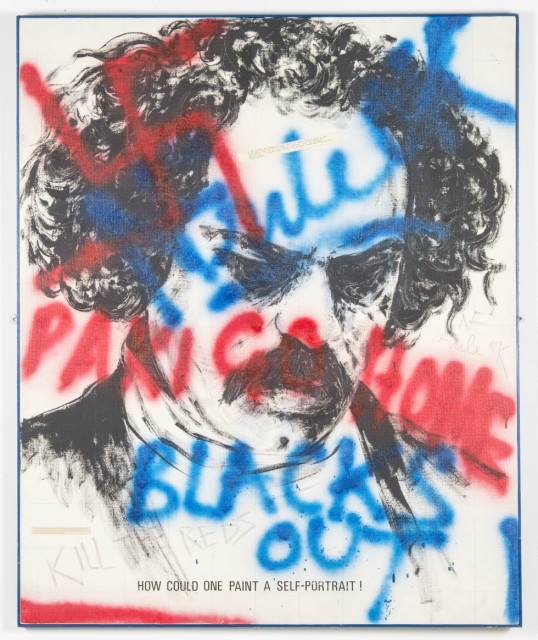

On the opening of Rasheed Araeen: A Retrospective, at BALTIC, Emma Sumner spoke to the artist, and took the opportunity to discuss global art history and what diversity in our national institutions should, and could, be…

A pioneer of minimalist sculpture in Britain, Rasheed Araeen received little recognition for his contributions to British art; his work often evaluated instead within the context of his non-Western background. As a direct result, Araeen was one of the first cultural practitioners to champion the need of artists of African, Latin American and Asian origins to be represented by British institutions, but despite recent efforts to increase diversity within our national institutions’ programming, mainstream art history continues to marginalise their work. In an interview with Apollo, Araeen stated: “The basic issue in Britain today is the legacy of its colonial past. While colonised countries got so-called independence, the occupiers never went through decolonisation.” A sign that, at 83, Araeen’s radical stance remains unshaken.

Although Araeen had a deep-rooted interest in art from an early age, it was never a career that he planned to pursue, studying civil engineering at the University of Karachi, with a desire to become an engineer and an architect. But, in 1959, he realised that his mind was more inclined towards art and committed to pursuing it as a career, moving briefly to Paris. Inspired by British sculptors such as Anthony Caro and Phillip King, he settled in London in 1964.

The Double Negative: Your written work, and curatorial practice, has challenged the racism in art history that we sadly still see today. Although the work of Asian and African artists is creeping into the global art market, their presence is still missing from mainstream art history. How do you think this can change, and do you think it ever will?

Rasheed Araeen: You and me cannot do anything, the major institutions in Britain, if they take an interest and they change, they can do it, but they do not want to do it. Tate is a major institution in Britain, whatever Tate does, or does not do, is followed nationally, so the whole responsibility is with the Tate. I have been communicating with the Tate for the last 15 years with a proposal on how to change art history, but they would not implement it.

Do you think that major international collections acquiring your and other African/Asian artists’ works helps the situation, or do you think this is all part of the institutional need to become more diverse in their operations to help fulfil funding criteria and other governmental pressures?

Both. It does help, because it helps to discuss our diversity. Now people realise that in Britain that there are not only white artists, but there have also been artists from Africa and other cultures. But on the other hand, it was not because there was a change of view, they still have the same view, it was because Department of Culture’s government policy changed and they wanted cultural diversity and it became mandatory for the public institutions to follow. The instruction from the Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) was that if they wanted to get funding, they must follow their policy of cultural diversity and that’s how they began to acquire works from artists of other cultures.

As far as to the reason why they have acquired my work there is a secret subtext which I have not revealed to anybody. Because I can tell you, after what happened in London on 7/7, there was a big ‘hoo-harr’ about the Muslims in Britain and that they were not modern, were resisting modernity, that they were too traditionalist, and all this garbage was coming out from the prime minister as well as from the media. I got very angry, they were four individual criminals, why blame the whole Muslim community, so I wrote a letter to Tony Blair, giving an example of my work, explaining that this is what the Muslims have done in Britain. Why the establishment does not realise is not the fault of Muslims in Britain but the institutions which have been suppressing their contributions to mainstream modernism. I wrote a few letters and he would not answer me, but eventually, the correspondence went to DCMS, it was after that they contacted me to buy my work.

Do you think that, in a way, by writing that letter, you could say that you were the catalyst that brought about some of the changes that we have seen in our national institutions?

Could have been. Yes, maybe.

You talk about the 7/7 bombings and how the Muslim community is tarred by the crimes of four individuals, and perhaps in a similar way, your work has been conveniently slotted into Islamic art history, assuming, because of your background that this is what your work is about.

They tend to separate those artists that are not indigenously British, that means not white artists, there is a tendency to relate them to the culture they come from. It has been happening all the time, even in the ’50s when you have an artist from India – like Francis Souza – whose work was looked at in the context of their own culture rather than the modernity of their work.

And in turn, perhaps what was really influencing their work.

Yes, and we still have that problem now.

This exhibition is an important retrospective that spans your career interlinking all the elements that make up your practice and is touring to several European venues which is likely to bring your work to new audiences as it travels. Do you think that an exhibition like this will help to bring about a change in the trajectory of European art history?

It all depends on how this exhibition is received nationally. My feeling is that it will be ignored by the London press, by the London media, because the whole debate about art takes place in London. Until this work of mine enters the debate in London, nothing will happen, it will remain marginalised. The same way other cities in England are marginalised.

So, although BALTIC is a great institution, it is on the outskirts of that conversation, because the conversation is centralised to London which brings to the fore a separate issue of the London-centric British art scene.

The Van Abbemuseum first approached Tate with the touring proposal, and Tate said no. The BALTIC was the second institution they approached.

Do you continue to have regular conversations with organisations like Tate about how things could change?

I had for 15 years, but nothing happened so I said to them: “no, I do not want to talk to you anymore because you are wasting my time, but I do have other channels open to me”. People come to me for interviews, so my interviews are being published on different platforms, but I am not in touch with the mainstream art world anymore. I do not want to be, I’m fed up.

Emma Sumner

Rasheed Araeen: A Retrospective continues at BALTIC until 27 January

Images Courtesy the artist