“I have achieved a lot in 18 months. And haven’t treated people like a cock.” In Profile: John Tueart (Part One)

In an all-embracing long read, Jordan Harrison-Twist’s interview with actor John Tueart assesses the long wait for the limelight – via meal deals and Beckett…

If we can write off egg butties, for Christ’s sake, and Irn Bru, and coated raisins –in fact, shave off the gristle so we are down to the real contenders (and stop posturing, nobody really wants coronation chicken), what remains for the meal deal is about five options per component – 125 possible combinations. In any case, each recombines into a disappointing hokum in the stomach, and after half an hour passes, it is back to the taupe man who taps the arm of his glasses with some cress on him, and the resignation, and the feeling that city life, at least for the days in which it seems to continue irrespective of one’s place in it, is more predictable than what one’s younger self thought it might be.

There is something in managing timetabling, in staid expectations that helps one feel useful. But it wasn’t always the case – before you were told your eyesight wasn’t good enough to be a pilot or that you should have taken Physics to land rovers on asteroids – that so much of work begins and ends with the plea: Thank you for your email […] I look forward to hearing from you soon.

Samuel Beckett’s plays are born (perhaps a better word would be reanimated) from the elliptical nature of work and death. In Quad (1981), his television play, four hooded, hunched figures walk in sequence, describing the same path diagonally about a square. There is an elusive beauty in such repetition – the spirit of mechanical assembly and disassembly. The procession is a sort of choreographed agonal gasp: players enter and reflect one another, distinguished only by their coloured robes; then they check out, and one lonely figure traverses the route in isolation. Overtime.

In his better known play Waiting for Godot (1953), Vladimir and Estragon use the same semi-distracted cross-talk as colleagues embroiled in the meal-deal conundrum, following a route laid out by the feet of Quad.

E: I asked you a question.

V: Ah!

E: Did you reply?

V: How’s the carrot?

E: It’s a carrot.

V: So much the better, so much the better. What was it you wanted to know?

E: I’ve forgotten.

Although Godot is commonly read as an allegory for purgatory, there are many moments as a spectator in which I feel as though I am transforming into some devastated tree trunk, or the horizon line obscured with clouds of sulphur. The play is quite alive, living, and those who populate the auditorium are transitioning into the seats that hold them, the props by the stage-side, the very landscape of the afterlife. When Vladimir stands at the front of the stage, surveying the audience – “that tree… that bog. There’s not a soul in sight!” – he encourages Estragon to find a place to hide amongst us – “you won’t? [Vladimir analyses the audience] well, I can understand that”. So the characters in Godot are alive in some ectoplasmic state, but they are confined and tethered to the stage, literally playing life; and reverberating through all of Vladimir and Estragon’s actions is the famous evocation, repeated many times throughout: all that exists is but a reinterpretation of something more original, over and again, ad thanatom, ad infinitum, nothing to be done.

There are those who protest when the eminent heroes of a genre are refurbished, but there is perhaps no more fitting a play for such treatment than Waiting for Godot. Dave Hanson’s postmodern production even chooses to repeat the verb and preposition in the title, and Waiting for Waiting for Godot (which is itself a repeat of the full title of Derek Jarman’s 1983 short film) found a publisher in Oberon Books in 2016, before being committed to the stage at St. James Theatre in London a month later, then in Manchester at 53two in April 2018. The play follows Ester and Val, two hapless understudies backstage at a performance of Beckett’s original, wondering if they will ever get their deserved opportunities to tread the boards. It is more obviously played for laughs – Beckett’s absurdity is achieved at the level of language necrosis, and the disintegration of syntactical sense; whereas Hanson’s is situational (with an extended scene of a method actor’s channeling of an ape). But its shallowness does allow Hanson to subvert Godot’s worked to death ethos into a dying to work one – a clever use of that Beckettian ellipse. The play occasionally dips into the original but has no pretensions of embodying oblivion in the same way: there is a death, which is contrived to flesh out the play’s emotional core, but it is used instead to pierce the jealousy, paranoia, and apathy that the rest of the play builds up – a call-to-action before the end.

Everyday he went to the same shop for a meal deal with a friend, and they would vent about work, which was for them a law firm, Keoghs. He had studied English at university in Birmingham, before training for six years to become a lawyer with the blessing of his parents. And he hated every minute of it from start to finish. He was scared to tell his supportive parents of his feelings – for what parent would want their child to shun a lucrative law job – but he did when the right offer came along, and the offer was acting: to play the lead in an old friend’s production in 2013. He is John Tueart, a writer and actor from Manchester whose play The Egoist debuted at this year’s Manchester Fringe Festival, and another of his, The Agency, earned a second stint.

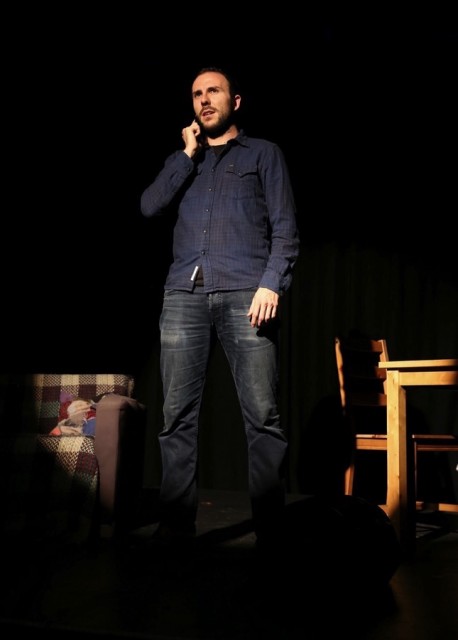

In a production of Waiting for Waiting for Godot in April (directed by Abey Bradbury), Tueart played Val – a character who we believe has some acting credo (because he believes he has some acting credo), but who we later learn is essentially a dilettante who covers his lacks with industry clichés dressed as wisdom. John played the part with a pathetic pomposity, popping his plosives as the audience filed into the space at the 53two theatre underneath the old Deansgate railway arches in the city centre. The venue, managed by Manchester Actors’ Platform, was perfectly suited for the play, as military-grade anti-damp fans, engaged in a losing battle with the Manchester climate, greet you upon entrance, and as you sit and watch the play, the distant rumble of Bolton- and Liverpool-bound trains can be heard overhead, as if the footsteps of the first choice for Vladimir and Estragon are hammering through the floorboards: a reminder of bigger fish.

But will they ever get the chance to step up, step out, into the limelight? For that, they must wait, and wait, for the opportunity. And when that moment comes we naturally respect (envy?) those who exchange the comfortable room beneath the stage for the trapeze above it, the pure pursuit of the art, whatever the risk.

“If you could say to me”, said John, when I met him at a pub close to 53two in Manchester, “that I would be able to sustain my life as an actor between now and the day I die, I would bite your hand off. But I’m a realist. I’m going to have something outside of the career of acting to keep myself afloat. I’m a qualified lawyer; I have the option of doing some consultancy or sitting at home doing some law work. This year I’ve not made much money at all, but I’ve got the earning potential of law right there – but… I just can’t face it.”

Tueart works on the bar at 53two when he isn’t taking roles, writing, or directing. He enjoys it: watching plays, meeting people in the industry, talking about theatre. It seems it must be stressed that there is a dignity in finding auxiliary work to maintain oneself as an artist, after the recent job-shaming of The Cosby Show actor Geoffrey Owens for working as a cashier at Trader Joe’s.

“We’re all just jobbing. Nobody is famous yet. Everyone is hustling. The majority of my work is word of mouth, I don’t have the luxury of cutting that line by being haughty or difficult. Even if it is unpaid or profit-share – I knew that going in. Go in, do your performance, see what happens. I just have to think I have achieved a lot in 18 months. And haven’t treated people like a cock.”

Tueart has recently appeared on television, in ITV’s Emmerdale, and in Victoria as the Speaker of the House, but the majority of his time has been spent finalising the scripts for his two plays at the Manchester Fringe Festival. His brand new play The Egoist enjoyed positive reviews in local press – earning Fringe nominations for Best Newcomer and Best Drama – and in it, Tueart takes one lead role and Sophie Giddens, the other. Wendy Patterson plays Maggie, Jake’s mother, and between the three characters, The Egoist steadily knits itself.

“My new piece is about a guy who moves away from home for work, and later moves back home after the death of his Dad, to check in on his Mum. He happens to have a chance encounter at a coffee shop he used to go to with a girl called Paige, and they strike up a relationship. It’s all about how their relationship develops. He is forced to confront his past, his relationship with his mother, with Paige. You don’t need much to create watchable, thrilling stories. You just need people.”

The son of ex-Manchester City and England footballer Dennis Tueart, John is honest about his upbringing. Acknowledging the good work of local actress Maxine Peake in striving for more acting opportunities for people from working class backgrounds, Tueart tells me he finds specific encouragement for representation in theatre to be condescending to an industry that should, but often does, do better. To some extent class is a consideration in The Egoist, too, but it manifests itself in the dog-eat-dog classroom environment of a high school. An interesting quirk is that the winners are often unaware of the collateral they leave trampled behind them, until such time perhaps when their own interests are aligned with those of their victims. It is a good script with strong performances from the two leads – Sophie plays the part of Paige as if with a splinter and so can flit between emotionally wise, and callow and haunted (the caprice of mourning) with great sensitivity; John’s Jake is more reserved, but in service of the sickening denouement – which I shall not spoil.

The first half takes a while to establish its environment, sometimes getting bogged down in tempting contemporary details such as Tinder, Love Island, Uber, and Loose Women – it so thoroughly populates the present day with its baubles that it flirts with becoming banal, and the well-written and well-performed social dynamics of the couple shrink away with the crumbs down the sofa cracks. A great lover of detail, Tueart explains to me one of the first characters he portrayed in an acting class: “I was performing a soldier suffering with PTSD, which I researched by looking at images of war. I was demonstrating the ticks he had, as well as his upright readiness – all a little bit too much. My teacher said it was a good portrayal, but to sit on it. To remove the conscious decision, the put-on, the exaggeration.” Where it counts, The Egoist does this, submerging the social plea at its core enough for its characters to flourish, and, after its stinging midpoint mood shift, to wither.

The subtext of the play has an added urgency in the wake of #MeToo: namely, how are otherwise good men enabled by their relationships to remove themselves from their actions? Jake’s loving, bereaved, mother sees only the image of Jake she wishes to, and with such unerring positive reinforcement, she lends her supportive hands to the construction of the dangerous egoist. The very best writing reaches out into the ramshackle village of seats before the stage, and draws you into the painful spasms of the characters before you; it expels you unawares, but marked by this hostile connection. The Egoist does this most effectively in the recognisable interactions between Jake and his Mum, at once prosaic and sweet and melancholy and silly, as those interactions are, but always in the service of the play’s refrain: the rules don’t apply to me. And beneath this always is Sophie’s broken performance as Paige – unable to give voice to the savagery of her repressed rage and bereavement. But when she does learn of Jake’s buried misdeeds, she finds the strength to cut through the roux of her all-rightness.

The climacteric has Paige cry “I trusted you”; and when she does, there is something in the utterance that swivels in the wound. It is not the trust she accents as failed and disgraced, but the you: you all, you Jake, the everyman, the good man, you.

Jordan Harrison-Twist