“It asserts that cinema retains the power to surprise…” In Profile: Irma Vep (1996)

With his latest psychological thriller, Personal Shopper (2016), debuting on Netflix UK recently, Mike Pinnington takes an opportunity to look back at French director Olivier Assayas’ 1996 breakout success: his ‘very meta’ Irma Vep…

If Olivier Assayas’ 1996 film Irma Vep was released today, it would most certainly be described by reviewers and critics as ‘very meta’, or, perhaps, intertextual (depending possibly on which of those two camps the writer fell into). In 1996, however, it is safe to presume that the term ‘self-reflexivity’ figured pretty universally. Whatever linguistic parlances you prefer, the fact is that Irma Vep is very meta indeed. Its title is drawn from Louis Feuillade’s seminal silent French serial Les Vampires (which appeared in ten parts between 1915 and ’16), about a gang of ruthless and cunning master criminals, terrorising night-time Paris and its citizens. Irma Vep (an anagram of Vampire, of course) is one of the serial’s central and – clad in a risqué skin-tight hooded body suit – most memorable, characters.

The remake of this touchstone of French cinema is proposed by director René Vidal (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud), envisioning Maggie Cheung (who plays herself) as its lead. A child of the nouvelle vague, it quickly becomes apparent that Vidal is a man out of time, a diminished, perhaps even spent, force. That the role is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who appeared in numerous films of the famed movement, including some of those by two of its figureheads, Truffaut and Godard, adds a particular frisson to proceedings. In the first instance, then, the film can be read as Assayas recognising, even paying homage to, those that had gone before him. Indeed, speaking about his casting of nouvelle vague actors such as Léaud, Assayas has said that “they are obviously actors of their generation that I respect. They have an approach to acting that is close to what I expect. Also”, he continued pointedly, “they don’t get much work in the French cinema these days”.

This is Assayas ruminating on some of the big conversations around French cinema at that time (many of which continue to this day, more than 20 years later), long after the legendary French journal Cahiers du Cinéma established film as the ‘seventh art’. Of course, such conversations cannot go on in isolation. In casting Cheung, a prominent figure of the then new cinema of Hong Kong, Assayas raises another question: in a globalised film industry, what is French cinema’s relationship to itself, its audiences at home? Additionally, what place does it occupy internationally? By extension, this speaks to what it means to make film under the looming shadow of the monolithic Hollywood machine, a shadow that casts itself so widely as to suggest that this alone is what constitutes Cinema with a capital ‘C’.

These conversations are at the very surface of dialogue between various characters – leading and otherwise. We hear from a journalist interviewing Cheung who speaks of his love of the balletic action sequences pioneered by John Woo, and his distaste for what he calls the navel-gazing of his own country’s filmic output; Cheung and Zoé (Nathalie Richard), who works in wardrobe, discuss the relative merits (and lack thereof) of Hollywood action films such as Batman. Zoé bemoans remakes, too, yearning for more original, ‘personal’ films. That Cheung, who can’t speak French, is cast to star in a French film, deliciously highlights the rich ambiguities and ambivalences set in motion here; additionally, the French movie we see (incidentally, Irma Vep was the first of Assayas’ films to be distributed in Britain) happens mostly to be in English.

But paced and structured like a typical multiplex release, alongside the reflection and interrogation, there are also moments of great humour, drama and (unfulfilled) romance. Updating Irma Vep’s leotard of the 19th century Les Vampires leads Zoé to sourcing latex bondage gear from a sex shop. Zoé, who is rarely seen without a cigarette in her mouth, tries on the suit’s sealed mask, and billowing plumes of smoke emerge a fraction of a second later. It is thrilling, too. In one scene we follow Cheung back to her hotel room, where she is playing Sonic Youth. Either going full method or in a state of possession, she fully inhabits – or perhaps is inhabited by – Irma Vep, and embarks on a daring raid, in which she steals the jewellery of a fellow hotel guest. Finally, of course, everyone (Zoé and Vidal in particular) is in love with Cheung, whose magnetic presence and psycho-sexual alter-ego/persona makes her muse, subject, object and ‘other’.

Irma Vep can be enjoyed in manifold ways, then; it both masquerades as and is the (then) young director’s breakout success, while a surreal quality runs like a rich seam through Assayas’ Irma Vep as surely as it did the original. It is, however, in the end best understood as a probing film essay – albeit one with a familiar narrative structure. In the final moments of the film, cast and crew (including a replacement director drafted in for a frazzled Vidal) settle down to watch the roughs of the old director’s presumed latest flop. We are greeted instead by a great visual triumph for the maligned director (which I won’t attempt to describe in too much detail here). Frames of the movie have – in avant-garde fashion – been altered, scratched with a pin, producing a vibrant new visual take on Irma Vep and Les Vampires. It calls into question everything we have been told: about Vidal, about French cinema’s presumed state of ennui, and most importantly, it asserts that cinema retains the power to surprise, delight and to exceed expectations.

I also like to think that there is a message there, one beseeching us not to so quickly forget those who blazed a cinematic trail. With Vidal’s scratching of the film, is Assayas reminding us that one of the nouvelle vague’s central tenets was to emphasise narrative cinema’s artifice?

Mike Pinnington

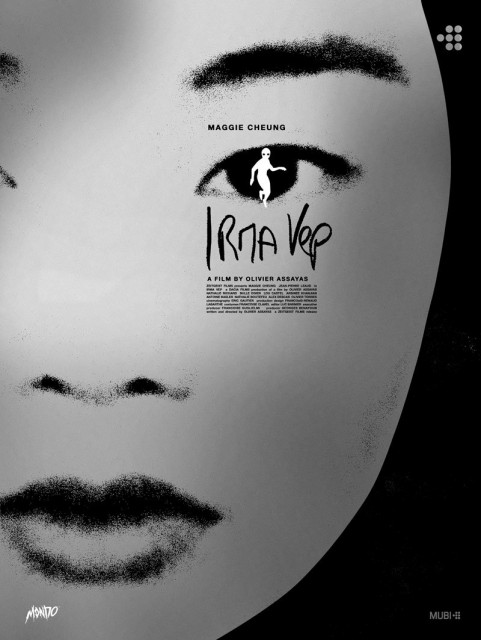

Images from top: Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep (1996) — still. Centre: Mondo poster designed by artist Sam Smith for Irma Vep and MUBI. Part of MUBI’s New Art for Timeless Cinema series

Olivier Assayas’ Irma Vep is available to watch on MUBI until Friday 5 January 2018, and Personal Shopper (2016) is available on Netflix UK now