“Abandoned and neglected memorials”: Mccoy Wynne’s The Other Self

![]()

In an essay by Julia García Hernández, photographers Stephen McCoy and Stephanie Wynne are seen to channel obsolete trig points and ruins in barren landscapes…

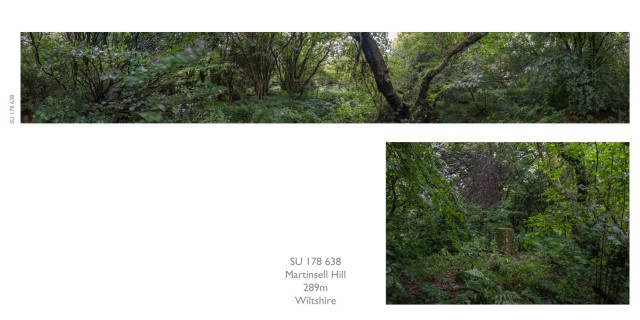

The project Triangulation is made up of two types of picture: a 360-degree, multiple frame, panoramic ‘view’ taken from a primary triangulation (or trig) point; and a single frame photograph of the concrete trig pillar. The dual worlds of the view and the material thing at its centre contrast not only in photographic form but also in the treatment of the subject: the view is determined by the position and height of the trig point on top of which a camera is placed; the pillar is a feature within a selected landscape scene.

Informing this project is the picturing of the American landscape, from 19th-century survey photography through to the man-altered landscapes of the New Topographics. (1) In The Rephotographic Survey Project of the late 1970s, Mark Klett and his team relocated the vantage points from which Timothy O’Sullivan, and other survey photographers, had recorded the American West.

Published in 1984 as Second View, it paired the same view one hundred years apart. Although rephotography features in earlier projects by McCoy Wynne, the repeat in Triangulation relates to the survey, rather than the image, since the project follows in the footsteps of the teams who measured and mapped Great Britain during the Retriangulation of Great Britain from 1936 to 1962. A camera and tripod replace the optical theodolite that would have been fixed into the top of the triangulation pillar.

![]()

McCoy Wynne’s ‘second view’ re-pictures the graphic of the Ordnance Survey map as a photographic, multi-directional view, visually connected to other triangulation points lying on the distant horizon. As an impossible view, it is as faithfully unreal as Ordnance Survey’s abstract landmass of lines and symbols. The addition to McCoy Wynne’s second view is the image of the solitary pillar. It is in the pairing of the view with the pillar that Triangulation can be understood, like Klett’s project, as both “science and art [that] somehow joins celebration and melancholy”. (2)

As mapping tools, trig points have been rendered obsolete, unable to fulfil their primary function by a new mapping technology. An unseen, and intangible, constellation of space-based satellites has usurped the network of land-based pillars. (3) Man is losing his material world. Acknowledging the consequence of this loss evokes a melancholy: “the object world […] is the other self of each of us, the alter ego without which we cannot be ourselves”. (4) As if to confirm Man’s dependency on the object world, the remaining trig points retain their alternate role as navigational landmarks and tangible stones for the hill and mountain walker. The concrete pillar, and its photograph, tether the view and locate the viewer; burrowed into the earth’s surface, more buried than revealed, the pillar acts as ballast to the view. And the view is a land without borders, traversing counties, and embracing a complete and varied British topography. (5)

The photographs of the view and the pillar invert our expectations. The view forms part of a catalogue of which a completed collection, from all 314 primary triangulation points, will visualise the entire land surface of Great Britain providing a visual survey. The man-made pillar, which could have been treated as a neutral typology, responds to its nomenclature. Exchanging the term ‘triangulation point’ for ‘pillar’ shifts the language from the mathematical and functional – and now obsolete – to the architectural and the romantic notion of the ruin. As ruins, the pillars are abandoned and neglected memorials within a sometimes barren, sometimes picturesque landscape.

Either one of the two photographers who make up the partnership of Stephen McCoy and Stephanie Wynne will set up the camera equipment to record the view. This part of Triangulation is determined by a procedure that is repeated at every location; 12 frames taken at 30-degree increments become a complete panorama. Having recorded the view, the photographers turn their cameras to its centre point. McCoy and Wynne take numerous pictures of the triangulation pillar – all at this stage possible partners to the view – in a process that occupies the most time on site. The dualities within the project extend to McCoy Wynne. This is a project of two pictures and two people, each taking co-ordinates from the other, each dependent on ‘the other self’.

Julia García Hernández (b.1970) studied the History of Design and the Visual Arts at Staffordshire University (BA, 1994), and Museum Studies at The Textile Conservation Centre, Winchester School of Art (MA, 2006). She is an independent writer and editor.

Triangulation was shown as part of the Northern Eye Festival Fringe in Colwyn Bay, 9–21 October 2017

See Stephanie Wynne at the Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool, as part of the Cultural Shifts project, until 22 December 2017

Notes:

1. The exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape showed in 1975 at the George Eastman House, Rochester, New York

2. Scientific American quoted in Klett, M. 1984. Second View: The Rephotographic Survey Project. USA: University of New Mexico Press

3. Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)

4. Susan Pearce, in Pearce, S. M. 1997. (ed.) Experiencing Material Culture in the Western World. London: Leicester University Press, p. 3

5. In The Panoramic Image the art historian Brandon Taylor explains that “the word ‘panorama’ conjoins the Greek meaning ‘all’ with ‘view’: the conjunction literally means something like ‘all-embracing view’ or ‘entire view’.” Published 1981 by The John Hansard Gallery, University of Southampton.

A version of this article first appeared in The Royal Photographic Society Contemporary Journal, No. 55, Spring 2014

Images, from top: Ditchling beacon, detail, and with panorama; Martinsell Hill with panorama. Feature image: Garnedd Ugain, detail. All courtesy the artists