Endings And Beginnings Of A Nuclear Power Station: Power In The Land

Stephen Clarke charts the work and current exhibition of an unusual art collective; brought together by a shared interest in Wylfa Nuclear Power Station…

The closure of a nuclear power station was the starting point for the project Power in The Land. An ending became a beginning. This simple observation demarcates a distinct border between past and future, but prompts the question: Can a nuclear site truly come to an end, at least an end that is observable in the present? It is at this juncture that the differences between the limits of history and the infinity of time are apparent. If history is the record of past events relevant to man, then the event of the site’s ‘official’ closure may be observed. Time, however, is more elusive, something man attempts to measure, using the mechanics of the clock combined with the uncertainty of personal memory.

Reactor One at Wylfa Nuclear Power Station on the Island of Anglesey was shut down on 30 December 2015. The penultimate day in the calendar, and at the cusp of the New Year, this date symbolizes endings and beginnings. Living close to the site of the power station, artist Helen Grove-White recognized the significance of this moment for the inhabitants of the area and a wider population. In the year before power generation came to an end, she brought together a group of artists to explore the meaning of this event. Conscious of their combined identity, the 10 artists united as X–10.

In her essay Time will Tell, Ceri Jones identifies themes that pull the group together: camouflage and invisibility, radioactivity, the domestic, and materials. She pairs Helen with Annie Grove-White under the theme of “artists’ experiences”. Their pairing is significant. The closure of the Wylfa plant provokes an inevitable correspondence between Helen’s present life and Annie’s earlier life. For the sisters-in-law, their individual experience of this specific place has formed an inescapable imprint on their lives.

Pressing her body against the fences surrounding the nuclear power plant, Helen Grove-White’s presence is made physical through her working methods. She uses a printing process that sits at the beginning of photographic history: the cyanotype. Discovered by John Herschel in 1842, these blue prints of camera-less photography require contact with an object to leave an impression on paper. In 1843, the botanist Anna Atkins applied the cyanotype process to scientific purpose with the publication of her book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. Atkins referred to her subjects as “flowers of the sea”: an aesthetic phrasing that links the histories of science and art. Grove-White’s use of Herschel’s process re-enacts the earlier works by Atkins; science and art meet again, but this time, it is the imprint of technology rather than organic material that is pressed onto the sensitive surface of the photographic print. Grove-White’s cyanotypes record the impression of the perimeter security fencing. In these prints it is not the power station that is documented, but its physical boundaries.

Measurement is a fundamental component of science. Although history is not a science it relies upon the measuring of time. The closely related discipline of archaeology has to dig deeper than written documents and recorded memory, in many instances delving into periods before history — into pre-history. Geological time ventures even further back to the beginnings. The centuries of the known turn into the millennia of archaeology, and then into the incomprehensible billions of years that are the scope of geology.

To describe geological time, the 18th-century geologist James Hutton developed the philosophical concept of “deep time”: an undercurrent that lies beneath man’s experience. Ernest Rutherford, the father of nuclear physics, applied his principle of the “half-life period” (1907) to determine the age of rocks, thus providing some measurement of deep time. The physicist, Hans Geiger, working under the supervision of Rutherford, developed an instrument that provides an audible record of radiation and captures a moment of deep time (1911). What is heard from the Geiger counter indicates an ongoing process of radioactive decay that exists in a time frame beyond apparent physical change.

Sound artist Ant Dickinson adopts the Geiger counter as an emitter of noise. He replaces and manipulates its count of radioactivity in order to create a random and shifting composition. The peculiarity of the measure of radioactivity is that not only does it extend backwards in time to an undefined beginning, but it also reaches to an un-foreseeable future. In addition, geological time can be measured by the strata of the rock beds where layer upon layer of rock lie on top of each other. This process of over-lapping can lead to the appearance of distinct time periods but can also become a blurring of minute features. In a film by Tim Skinner, the power station melds into the surrounding landscape, seemingly consumed by the ground beneath, becoming yet another layer in the larger geomorphic time frame.

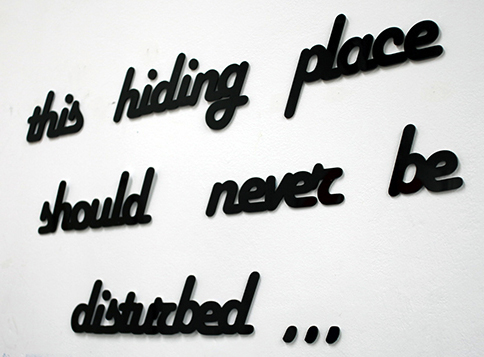

The artefacts of archaeological time are more tangible; made by man, their reality is grounded by the link to our ancestors. Although archaeology has a narrower scope than the deep time of geology, its future projection is less determinable. How will the distant descendants of present-day archaeologists interpret the remains of Wylfa? Teresa Paiva (pictured, above) addresses this question by referencing Finland’s underground storage facility for nuclear waste. Onkalo, the subject of the film Into Eternity (2010), is intended to remain sealed and undisturbed for one hundred thousand years whilst its contents decay. She utilizes the film’s cautionary warning: “This hiding place should never be disturbed”. Archaeological time is projected into a future. Paiva’s copper modular forms are continually re-constructed at each location where the work is displayed. The act of re-interpretation continually shifts possible meanings for these objects, mirroring the speculative process of the archaeologist in relation to the products of antiquity.

The archaeological process is a feature of the work of Robin Tarbet who has taken casts from around the site of Wylfa nuclear power station. Similar to the plaster casts that are made of the relics of ancient cultures, as well as suggesting the fossil collecting of palaeontology, Tarbet’s concrete samples are evidence for the audience to interpret. The artist’s impressions are pulled from the time and place but their meaning is left at the site.

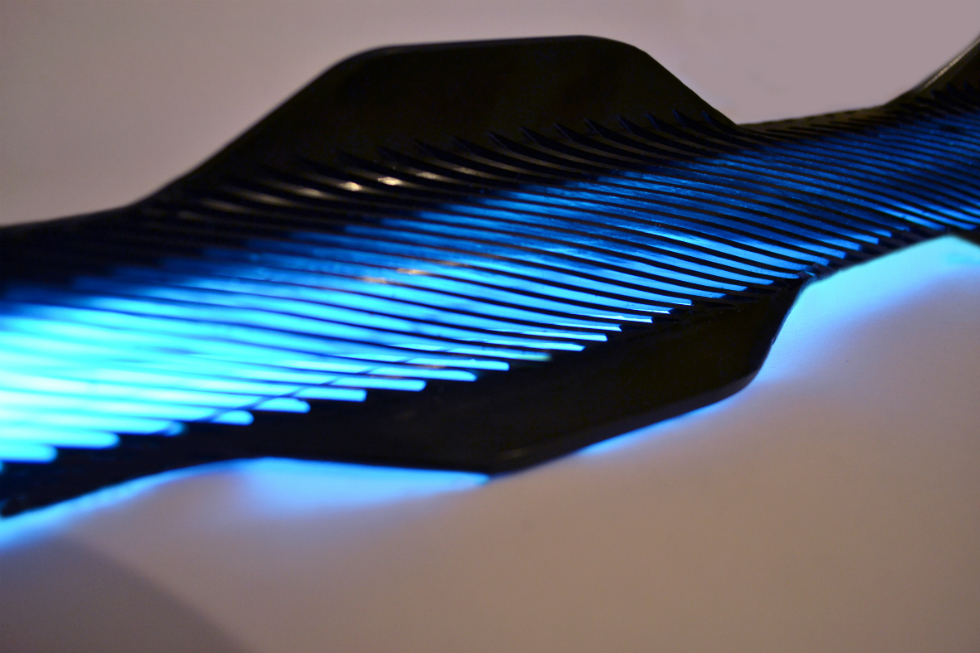

The artefacts made by Jessica Lloyd-Jones (main image, top) are more recognizable. The slim, finned objects are replicas of Magnox fuel elements. At the core of each piece are slithers of illumination from blue xenon and purple krypton light sources. The aesthetic is modern, bearing a kinship to the neon light sculptures of minimalist Dan Flavin, and so ties advanced engineering of the 1960s to its contemporary in avant-garde art.

In his essay Layerings and Journeys, Steffan Jones-Hughes makes connections between technology and modern art. His story of this part of North Anglesey weaves together a register of people, events and dates. The narratives of historical times provide familiar coordinates. Generated by language as well as evidence, history permits a meaningful discourse. The project’s title, Power in the Land, directly refers to the power station in Anglesey, but could equally apply to the castles of North Wales that are a past manifestation of imposed authority.

In the film produced by Chris Oakley (pictured, above), these two periods of time meld as Wylfa, the power station next to the sea, takes the guise of a shimmering fortress. Oakley digitally manipulates his images to produce what appears as an illusion, or Fata Morgana. This very particular mirage, named after the sorceress Morgan le Fay, directs attention to a mythological Welsh past. Like the fairy castles created through the enchantment of Morgan, Wylfa projects its power in the landscape of this region. Oakley’s film invites these correspondences between the cultural and political histories, and the current mythologies of nuclear technology.

The work of Bridget Kennedy also moves between past and present. East of Wylfa, the copper ore of Parys Mountain has been mined since the Bronze Age. Its soil lacks life. Contamination from industry has an historical provenance. Taking the material product of this earlier industry, Kennedy has made a series of weavings with fine copper threads. History is implicitly recycled in these works as redundant copper is re-used, and its potential to contain the radiation of contemporary industry is alluded to.

Recycled history underpins the quilts made by Alana Tyson. As a Canadian artist she brings with her a tradition of the use of patchwork as a method of communication. Quilts carry messages in anti-nuclear protests as well as providing a comforting bedcover. The composite nature of the patchwork quilt incorporates fragments from other items of clothing, each with their own mnemonic residue. Tyson utilizes a domestic vocabulary of the quilt and the wooden-panelled door to reference history on the more personal scale of the home.

Human memory is a limited measure of time. Unlike time measured by geologists, archaeologists and historians, memories exist in a fluid and unstable state. Annie Grove-White’s experience of the perimeter security fence at Wylfa is not the physical boundary that her sister-in-law charts, but rather a psychic one that separates the time before Wylfa from the time after. The artist grew up close to the nuclear power station: it is part of her past; it is her beginning. Returning to this area and the memories of the early days of Wylfa, she collected the impressions that the plant’s arrival made on the local people. In contrast with the prints made by Helen Grove-White that connect photography with the physical sciences, Annie’s photographic work is related to anthropology. Her video pieces explore the short expanse of what a person experiences. Time becomes domesticated, tied to everyday usage.

Existing in a moment, the closure of Wylfa does not represent an ending, merely a coordinate in an expanding temporal field. Its overt importance is the stain it leaves; however, the underlying significance is the meaning that this event has upon our relationship to time. Essayist Ele Carpenter sites the work of X-10 within the Nuclear Anthropocene — one part of the geological epoch that began with man’s impact on the planet’s ecosystems and its geology.

Another measure of the eternal, the use of this concept demonstrates our habit of segmenting the universal so that our minds can comprehend it. Unlike science, art is less defined relying upon spillage — slipping between designates — so that geological time, archaeological time, historical time, and memory, interact. The response of the X-10 artists to the closure of the nuclear power station reaches beyond the immediate event to consider the extended meaning of this place.

Stephen Clarke is an artist, writer and lecturer based in the North West

X-10′s exhibition Power in The Land, at Bay Art Gallery, Cardiff Bay, runs until 17 March 2017. This forms part of an international tour

The book X-10 Power in The Land (2016), edited by Helen Grove-White and Annie Grove-White, includes essays by Ele Carpenter, Steffan Jones-Hughes, and Ceri Jones

Images, from top: Jessica Lloyd-Jones, Black Rod; Teresa Paiva; Chris Oakley, Fata Morgana; Power in The Land installation shot

Read Stephen Clarke’s An Archaeological Impulse: Robin Tarbet

See Stephen’s exhibition End of the Season at The Vallum Gallery, Institute of the Arts (University of Cumbria), Carlisle until 26 February 2017; and then at Weaver Hall, Northwich 18 March–19 July 2017. Read more about the show here