“Visualising our horrors of dystopia” — Introducing: Mould Map Magazine

With issues taking the form of radioactive time-capsules about misinformation, or (most recently) exhibitions about terraforming, Jacob Charles Wilson’s love for Mould Map lies in its format-changing, “ugly”, and abrasive commentary…

It’s increasingly unlikely that in 30 years there will be many people left to look back on the mid-2010s, but assuming there are, perhaps with hindsight they’ll turn towards why our vision in 2016 was so blinkered, seemingly careering towards terrifying monolithic barbarism as progressive possibilities were denied and denigrated. They could point to the possible futures that existed. Of these, one is to terraform: to turn the massive productive efforts of the Anthropocene away from the production of waste for waste’s sake, and into reversing climate change; or even producing new habitable locales, regions, or planets themselves.

The notion of making worlds has underpinned Mould Map — a compendium of comic artists, illustrators, digital designers that, on its inception in 2010, was never really concerned with nerd and fandom. Co-publisher Leon Sadler tells me it has morphed over the five previous issues into a publication “more interested in wider social conversations we can have through goofy comics and ugly graphics”. Mould Map visualises our horrors of dystopia, the negotiation of life with neoliberalism, and speculative futures of gender.

I’ve been following Mould Map since Issue Three — the crowdfunded edition that redefined the magazine from a thin riso-print to a high gloss, high cost, and high desirability compendium. Issue Four, EuroZone SpeZial, published in 2015, seems particularly prescient, working over ideas surrounding the EU, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), Investor State Dispute Settlement (IDSD), and counter-cultural anti-nuclear movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. This year’s Issue Five, Black Box (pictured, below), looks at stealth, misinformation, and obscurity; rather than a bound magazine, it’s presented as loose leaves tied together with rubber bands, occupying a space somewhere between Shibari rope bondage and Cordura combat gear.

Mould Map is a robust refusal of a single style, that assimilates sci-fi aesthetic with a glitchy present, wrapped in a radioactive, lurid design, and which looks like it could survive an inevitable nuclear winter long after the quiet pastel-hued lifestyle mags perish. My enjoyment of Mould Map is in the fact that it’s abrasive, and it resists reading. It’s not only hard to find a copy (they sell out fast), but the act of actually turning the pages, crammed with text and imagery which rarely follow a chronological narrative, demands that readers and viewers return, preferably with a microscope or x-ray scanner.

For the sixth Issue, entitled Terraformers, Nottingham-based designers and editors Hugh Frost and Sadler, in true fashion, broke the book format to curate an overwhelming physical exhibition in Nottingham University’s Bonington Gallery (pictured, top). With their own backgrounds in small-press comics and illustration, Frost and Sadler are well-placed to organise such an enormous event. Together, they run Landfill Editions, which publishes Mould Map, as well as single issues mainly from UK-based artists, but with some from Europe and the US.

The exhibition presented the work of over 50 new and previously featured practitioners, that goes beyond simply illustration to incorporate archive material, computer games, 3D design and sound works. These include installations by Lando, whose single line illustrations of pyramids above desert landscapes draws on the 1970’s visions of decayed galactic civilisations. For Terraformers, he uses a museum-style vitrine to display ceramic tablets and Penguin books-style pamphlets that describe ancient lizard-people and mushroom parasites.

Kitty Clark presented a videogame navigated using a handheld roller ball mouse; a terrible controller particularly for first-person games such as this. It’s a small detail, an anachronistic throwback to the mid-2000s, one that made me smile, and a reminder of how far even in 10 years we’ve come in our understanding of computer-human interaction.

Jacob Ciocci (pictured, above) showed FREEDOM ISN’T FREE/I’M NOT CRAZY, IN AN INSTITUTION, SOCIETY IS CRAZY, IN AN INSTITUTION (2016), a video on a desktop monitor that fills the room with ominous music, over footage of wind farms being destroyed in storms, as Minion and Barney The Dinosaur inflatables careen down streets in high winds. It’s tacky; it’s also the boring dystopia that we live in.

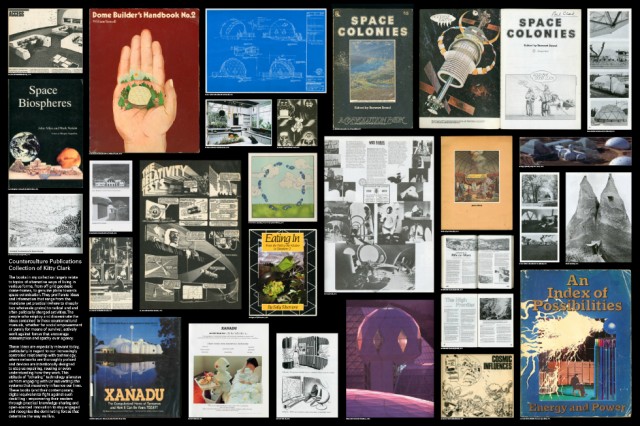

Secreted between the garish screens, I found sincerity in many of the works exhibited. Particularly, the archival material of the potential futures, which appear now so vibrant and optimistic alongside our own ironic projections. Alongside her videogame, Clark also showed the Counterculture Book Archive (pictured, below), a series of covers and articles from the utopian earth movements of the 1970s that espoused ecological harmony, through DIY projects and a return to nature. At the other end of the potential futures scale is Hui-Ying Kerr’s Bubble Economy Magazine Archive in Japan, which shows a decade of prosperity in Post-war, Post-occupation Japan; powered by the rapid and enormous growth of the electronics industry, and prompted the cultural imaginings of new humans. Lifestyle magazines grew around these cultures before, inevitably, the bubble of prosperity burst.

What’s clear is that the idea of the future has continually been presented and understood through publishing cultures. The concept of Terraformers itself resembles the design and aims of the British magazine Quest, or an issue of the radical ecological DIY magazine Whole Earth; drawing on hippy culture, late-‘60s technocratic solutions, and communist, feminist leanings. Given Frost and Sadler’s own backgrounds are in publishing, I wanted to find out why they decided that this issue should be an exhibition.

“Many of the artists whose comics and graphics we’ve published also work with sculpture, video, textiles or painting etc.”, they tell me; “works that don’t necessarily translate well or at all in print. Also, it’s been such a pleasure meeting people in the space. If they follow Mould Map, or have never heard of it, it’s just been a much more social project for us.

“On the downside, the longevity of a printed artefact is hard to replicate, which makes us quite concerned about documenting things properly, so we’ll be using photography, drone video footage and 3D scanning equipment to capture the show.”

The current state of the UK’s small-press and graphic design / illustration field couldn’t be better. In addition to the larger comic fairs showcasing Indie work, there are a multitude of smaller events and organisations that showcase it too: East London Comics and Art Festival, plus Artist Self-Publishers’ Fair, hosted at ICA London, and recently Safari Festival, run by Breakdown Press. I asked Frost about Mould Map’s position and plans for the future.

“It would be great to see better distribution networks for smaller presses with irregular publishing schedules, but it would be such an epic task”, he says. “Leon and I are hoping to start working on projects together for others as Mould Map Studio, applying our combined type and illustration approaches for social campaigns (e.g. public ownership of UK rail) cultural projects (gallery materials / catalogues) and ethical brands (e.g. those working with low impact materials and accountable supply chains et cetera). Those would be our dream collaborations.”

There’s something in the name, Mould Map, that describes its own future. Mould, a multitude of structures barely on the edges of life that spread across existing fertile, yet neglected, surfaces to extract further nutrients. Map, the object that, in the words of Baudrillard, precedes the territory as a simulacra, creating the very space it describes, and the only thing that remains when the real erodes. This exhibition looks back — not far, well within living memory — to see how people envisioned our own present. Through this, we can understand and reflect on how we see our future(s), and imagine how this will exist in a reciprocal relationship with future people. In the past year or so, the notion of terraforming has entered popular imagination through the words of Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX (discussed in a recent article on this website). In the coming decades, it will be worth looking back to Mould Map to remind us that world-making is difficult, and that even our best ideas decay over time.

Jacob Charles Wilson

Jacob saw Mould Map 6: TERRAFORMERS at The Bonington Gallery, Nottingham, 17 September–21 October 2016

Read more information about Mould Map and its publishing house, Landfill Editions