“Bewilderingly kaleidoscopic”: Cécile B. Evans @ Tate Liverpool — Reviewed

Luke Healey finds a series of bewilderingly kaleidoscopic, emotive encounters between the human and the machinic at Tate Liverpool…

Describing Sprung a Leak, her new commission for Tate Liverpool, Belgian-American artist Cécile B. Evans notes that the work is her “first play in 12 years”. Evans is known for her video works exploring the emotional resonances of digital culture, but her origins as a practitioner are in theatre. The title of this work is lifted from The Two Noble Kinsmen, a Jacobean tragicomedy attributed to William Shakespeare and John Fletcher. Sprung a Leak contains an ensemble cast of characters, a script, and a three-act narrative full of love, death and crisis.

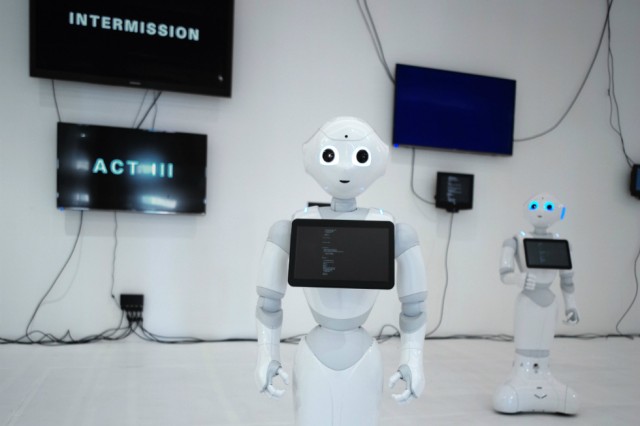

On entering the ground-floor gallery space in which it is housed, however, two things immediately mark this play as unusual. Firstly, there is no designated start time; no waiting for spectators to file in before the performance begins; no spatial separation between audience and cast. Secondly, there are the performers themselves: they are, scanning from stage right to left, a trio of monitors containing slowly-moving images of pole-dancing women, a pair of roving anthropomorphic robots, a CGI beauty blogger named Liberty who passes through a separate series of wall-mounted screens, and a small robot dog in a metal pen. Evans voices all the parts, but otherwise absents herself from the action, outsourcing the performance to these digital proxies.

Sprung a Leak’s plot is loosely based on the bizarre story of Marina Joyce: a popular British vlogger whose YouTube activity over the summer of 2016 led some of her followers – and a subsequent horde of online clickbait outlets – to hypothesise that she had been kidnapped by ISIS. Suspicious irregularities in the relevant clips include Joyce’s apparently disconnected attitude, the bars on her bedroom window, the bruises on the backs of her arms, and an ambiguous passage in which she can be seen to whisper “help me”.

Though the claim that Joyce was in any kind of danger has been roundly rebuffed, this fan theory led to the hashtag #SaveMarinaJoyce becoming a world-wide trending topic on Twitter, demonstrating the tendency of social media platforms to propagate what behavioural researchers have labelled “emotional contagion”. In Sprung a Leak, Joyce is transformed into Liberty, who dies at a pool party and is reanimated in the form of a status update. C Plot, the dog, falls in love with her; the remaining two robots, A Plot and B Plot, worry about C Plot and mourn Liberty. The three pole-dancers, known as Users 1, 2 and 3, constitute what Evans calls a “chorus”.

At various moments of emotional climax, a fountain in the centre of the room erupts. There are also tangential strands to the proceedings, which play out on the same monitors that Liberty occasionally inhabits. These relate to the NASA headquarters at Cape Canaveral, close to where Evans grew up, and more specifically to its recent privatisation at the hands of Elon Musk’s SpaceX company.

If this all sounds bewilderingly kaleidoscopic, it is. Evans has usefully provided visitors with a brief plot synopsis next to the gallery entrance, and notes that the whole piece can be fully appreciated in “about three cycles”. Even allowing for a full afternoon’s viewing, however, there is plenty here to wrong-foot or distract the spectator. The script – which can be viewed in draft form in a Google Doc shared on Evans’ website – is impressionistic, meandering through verbose or jargony passages and then busting into sudden panicked expletives. The disconnect of voice from performer – at no point do any of these “actors” move their mouths while delivering their lines – impedes an easy reading of who is talking when.

Most of all, it’s difficult to get away from the fundamental uncanniness of the robots Evans has employed: watching A Plot and B Plot use their gesturally-precise hands to signal anguish is a queasy experience; as I leave the gallery, a small crowd have gathered around C Plot, who has just woken up from a charging session, and are cooing over him. Members of the University of Liverpool-based robotics team, with whom Evans collaborated on this production, note that the humanoid robots used here were developed specifically with sociality in mind: the “Pepper” model, developed by Aldebaran Robotics and Japanese multinational SoftBank, can use its on-board camera to read facial expressions, and is used to provide customer service in SoftBank Mobile stores across Japan. For the viewer unfamiliar with Japanese mobile phone shops, the first thing that needs to be negotiated here – and it’s entirely possible that these negotiations will remain unresolved over the course of the visit – is the strange sense of social being that these robots exude.

A comparison that comes to mind in this respect is with the work of Ed Atkins. He and Evans evidently share an interest in collaborating with teams of technological experts to realise projects, but appear equally interested in interrogating certain social aspects of the technological processes they engage. In Performance Capture, Atkins’ project for the 2015 Manchester International Festival, the artist put his team of motion-capture animation experts on full display by bringing their studio into the gallery space; turning an ongoing labour into a kind of performance.

While Atkins’ collaborative partners had a professional interest in seeing to it that the project played out as smoothly as possible, the artist was keen to direct viewers towards the sweat and tears that underpins so much “disembodied” digital production. Likewise, Evans has set out in this project not just to deliver a narrative which speaks to the complex emotional landscape of online existence, but in addition, to do so by staging a series of strange and unpredictable emotive encounters between the human and the machinic. This applies as much to the viewer as to the gallery invigilators, who have been specifically instructed to treat A Plot and B Plot as if they were human performers.

More so than many artists drawn aesthetically to the kinds of slick digital interfaces on display here, Evans is an artist who is invested in interrogating the social, political and affective resonances of her chosen materials, and Sprung a Leak marks a turning point with regards to the scale and ambition of this ongoing critical project.

Luke Healey

See Cécile B. Evans at Tate Liverpool, ground floor Wolfson Gallery, from now until 19 March 2017 — FREE

Images: Cécile B. Evans: Sprung a Leak 2016, at Tate Liverpool. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Emanuel Layr, Vienna