Monuments Should Not Be Trusted — Reviewed

A new exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary brings together the largest ever selection of Yugoslav art in the UK from the ‘golden years’ of the Socialist Federal Republic. What emerges, finds Bob Dickinson, is a witty, gripping and extreme picture of social change…

Taking its title from Dusan Makavejev’s 1958 banned satirical film in which a young woman finds herself attracted to a muscle-toned male socialist statue, Monuments Should Not Be Trusted re-evaluates art that addressed the changing conditions in Yugoslavia between the 1960s and the mid 1980s. Positioned as “non-aligned” by its leader, Joseph Broz Tito, this communist country was neither part of the Russian-dominated Warsaw Pact or the capitalist West. And so, for a while, egalitarian ideals co-existed with the first influx of mass consumerism under ‘market socialism’, gender equality rubbed shoulders with girlie mags, workers self-managed while students protested and a new approach to making art outside the gallery system emerged.

The breakaway from traditional styles like socialist modernism was exemplified by groups like OHO, by the late 1960s influenced by Art Povera and land art, seen here in films like White People (1970), where the artists wrap each other in tinfoil, blow bubbles in milk, pretend to be sheep by sticking wool to their naked skin, throw down flour and roll around in it, and then, in the final scenes, set off smoke bombs in a bleached landscape of snow and fog. The group merged into the land, in fact, setting up their own commune in rural Slovenia in 1971.

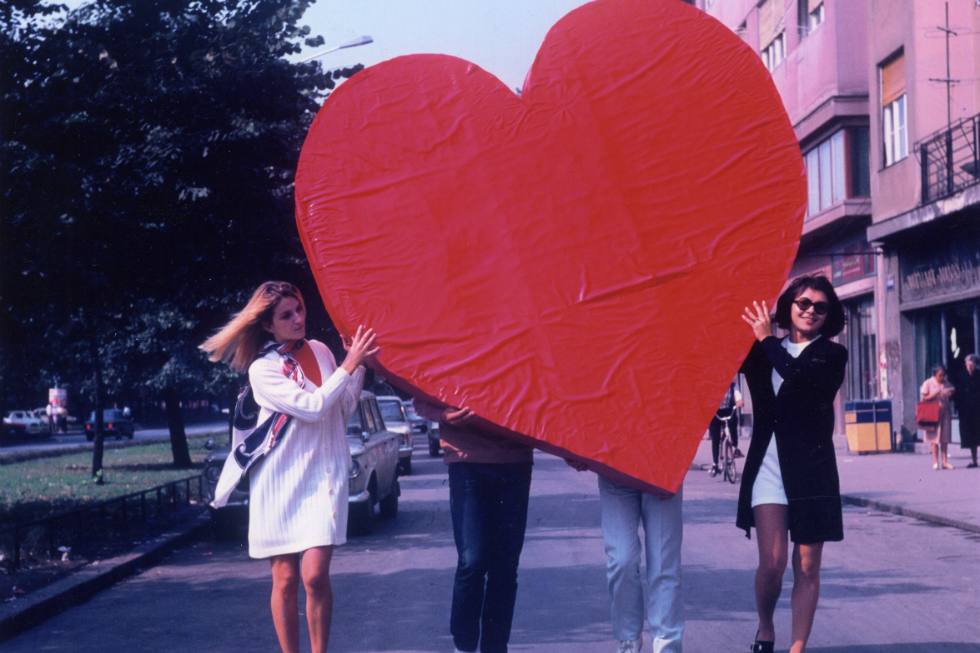

As elsewhere in Europe and the USA, Yugoslavia was convulsed at the end of the 1960s by student riots, witnessed in Belgrade by Zelimir Zilnik in his film June Turmoil (1968). The resulting provision of Student Cultural Centres (SKCs) to Yugoslavia’s bigger cities gave space for what was called the New Art Practice to emerge. Co-founder of the SKC in Novi Sad, Bogdanka Pozmanovic’s Action Heart Object (1970), is a film of her first performance in which she and others carry a giant, pink heart through the city centre, deliberately disturbing the evening rush hour.

One of Pozmanovic’s collaborators during the 1970s, Katalin Ladik, also became significant for performance. Olomontes/Lead Mining (1970) is a video showing one of her experimental explorations of folk-culture, featuring the artist playing a giant set of bagpipes and singing in her native Hungarian, distorting and testing her voice in a manner reminiscent of Cathy Berberian. Commenting on her relationship with the state, Ladik’s Identification, Action (1975) is a pair of photographs showing the artist standing on the steps of Akademie Der Bildenen Kunst, Vienna, first in front of, and in the companion photo, hidden behind, a giant draping Yugoslav flag.

Belgrade’s SKC was where Marina Abramovic and filmmaker Zoran Popovic made early work, seen in Lutz Becker’s Film Notes (1975), which includes early footage of Abramovic’s (subsequently influential) Art Must Be Beautiful, her facial appearance changing markedly with every stroke of the brush, fast and slow, brutal and gentle, combing and re-combing her hair. Nearby, there is a still photograph from Rhythm 5 (1974), where Abramovic lay down inside a burning symbol of state – a large star – before passing out due to a lack of oxygen, to her subsequent regret .

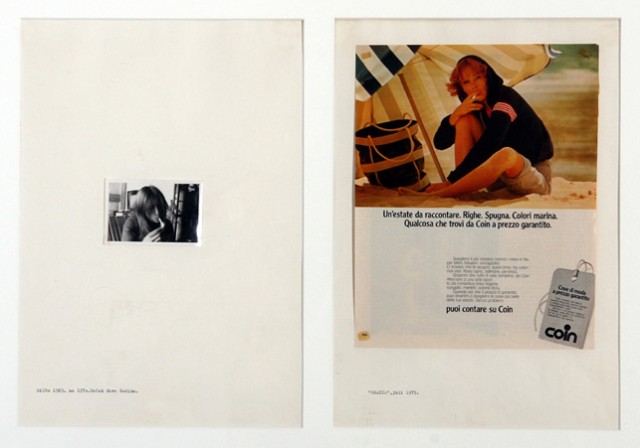

Some of the wittiest work on show reflects feminist responses to life in Yugoslavia. Zagreb-born Sanja Ivekovic’s Double Life (1975) is a photomontage in which images of the artist are carefully matched by posed models from fashion magazines. She does a similar ironic job returning to the subject of public monuments in Private-Public (Man’s Pictures Woman’s Pictures) (1981), in which a heroic female statue is surrounded by small photos of a young girl – the artist – dressed as a ballerina. In her video Personal Cuts (1982), Ivecovic snips holes in a stocking mask she is wearing, every cut cueing a flash of TV footage about Yugoslav history, directly introducing the personal into the political.

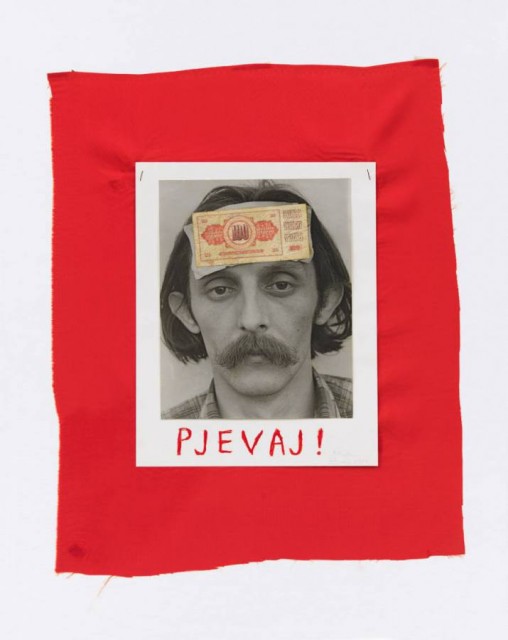

Much of what the New Art Practice produced was street-based, and apparently simple. Mladen Stilinovic’s short, sharp attacks on money and work are gripping. Sing! (1980) is a close-up photograph of the artist with a 100 dinar note pasted on to his forehead – a reference to the Balkan tradition of spitting on a banknote, sticking it to the head of a musician, and ordering them to perform. Much of Stilinovic’s work from this time uses socialist red, including the jokey, crayon pieces commenting on the emptiness of stock Communist party phraseology, such as Dead Bureaucracy Says to Another Dead Bureaucracy, You Are A Dead Bureaucracy (1980).

Pop culture becomes omnipresent in work from the 1980s, reflecting the impact of Yugoslavia’s punk and post-punk subcultures, particularly surrounding the Slovenian magazine Problemi and bands such as Borghesia, Lustmorder and Laibach, that emerged from it, all causing controversy for their use of transgressive and/or totalitarian imagery. The Youth Day Poster (1987), designed by the NSK/New Collectivism group, won a national competition that year, only to be banned when it was discovered the central image of a young, naked man carrying a torch and banner was appropriated from Nazi propaganda. Laibach continue to push extreme imagery beyond meaning, except, perhaps to the government of North Korea, where the band have recently toured.

While he lived, the presiding presence of Tito was for many a reassurance. Monuments Should Not Be Trusted features a collection of objects from Tito’s former Belgrade residence, now the Museum of Yugoslav History, including a series of carved batons used in athletic events from 1950s, sent to Tito by youth pioneers, trades unions, health professionals and teachers’ associations. There is even a bizarre sculpture made from a set of dentures, commissioned by the Alliance of Dentists of Yugoslavia in 1955.

But for others, Tito was an intrusion. Sanja Ivekovic’s Triangle (1979) combines four photos taken on the day of Tito’s visit to Zagreb. In one, the artist is sitting on a balcony, reading a book, and making “gestures as if masturbating”. Another shows what she should have been watching: Tito’s entourage. A third photo shows someone observing from the top of a nearby taller building. The fourth shows a policeman on the pavement below. During this artistic exercise, the policeman entered the building, knocked on the artist’s door and ordered “that the persons and objects are to be removed from the balcony.” Notions of privacy, surveillance, and ridicule for a culture based on a personality cult are all compressed into this work. We know what followed 12 years after Tito’s death in 1980: nationalism, federal breakup, genocidal violence, tragedy. This show brings to light the imagination let loose by what went before.

Bob Dickinson is a writer and broadcaster based in Manchester

See Monuments Should Not Be Trusted at Nottingham Contemporary from now until Friday 4 March 2016 — FREE

Galleries open Tue-Sat 10am-6pm; Sun 11am-5pm; Bank Holidays 10am-6pm

Dont miss: Unbribable Life: Art and Activism in former Yugoslavia and the UK (Protests, Plenums and the struggle for the commons) talk – 3 Mar 2016, 6.30-8.30pm (free, The Space). Hosted by Tuzla activist Damir Arsenijević and Artist Margareta Kern with contributions from DITA worker occupiers, ally Vanessa Vasić-Janeković and local activists Tom Unterrainer and Tony Simpson from the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation.

Plus Unbribable Life II: Art and Activism in former Yugoslavia and the UK (The Politics of the Art School: Study Day) – 4 Mar 2016, 1-6pm (free, The Space). Formatted around keywords, inviting past and present participants from the UK and Yugoslav contexts to discuss strategies and futures for their work in and across both contexts.

Images from top: Bogdanka Pozmanovic’s Action Heart Object (1970); Sanja Ivekovic’s Double Life (1975); Mladen Stilinovic’s Sing! (1980)