Why Do Galleries Exist?

C. James Fagan wants to be stimulated by the things he sees in the gallery. But is that what the gallery is for? Here, he ponders the broader purposes and concerns of our contemporary art spaces and their fundamental relationships with us — the people who visit them…

Why do galleries exist? This may strike you as a strange question. For the majority of people reading this article, galleries form an ubiquitous part of their lives and even careers. For many, viewing art also forms an important element of their social and leisure time.

Naturally, the first and perhaps the most obvious answer is that galleries exist to show art, to display whatever they see fit. Fair enough; but it also matters who is attending the gallery. The question of why galleries exist is related to another, key question: Who do galleries exist for?

How can we begin to understand or investigate what is a complex relationship between people and institutions? For the purposes of this article, I am relying on my own experiences as an art viewer with an art degree who has worked at galleries in my hometown of Liverpool; using the microcosm of one city in order the understand the macrocosm of the UK art scene.

Liverpool has galleries within a 20 minute walk of each other that offer an enormous range of artistic practice — from Greek sculpture to the latest digital technology to live performance (though they could offer more of the latter). I haven’t always been aware of these places; it was when I made a decision to take an interest in art that I sought out the gallery space.

My actions may indicate one reason galleries exist: that they are places to discover art. First, I had to discover what was available to me: this was done by scanning through the ‘what’s on’ or the ‘culture’ sections of the local press. Reading these listings for the names and locations of my local galleries allowed my imagination to be caught by a provocative exhibition title or description.

One of the first galleries I visited would have been Tate Liverpool. I can’t recall, but I was probably aware of its reputation for art, though it wasn’t quite the mega-brand it is today. Inside the Tate, I discovered a wealth of modern and contemporary work — exposing me to Marcel Duchamp and Helen Chadwick. At this time, I was taking in the works as an experience, picking up contextual information as I went.

In addition to Tate, the Bluecoat was important to my gallery education: an exhibition and performance space, plus studios and book shops, dedicated to contemporary art and artists based in the wider area. Visiting a gallery like the Bluecoat exposed me to new artists and current trends. Here was the opportunity to learn more about art.

This was important for someone like me, who wasn’t taking a direct route in art (I spent years studying design before fine art). Galleries were a valuable resource — especially pre-broadband Internet – which also informed and encouraged me to seek out more galleries in Manchester and London. This is my experience, the experience of one person.

So why do other people go to galleries? I’ve touched upon the element of education, but one very important reason that people visit galleries, museums or any other cultural attraction is to see ‘stuff’. Of course, this stuff has to be brought to the attention of an audience – you can’t see some stuff if you don’t know there’s stuff to see.

I saw an example of this during a recent visit to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, where there were a large number of visitors. More than usual, many of these visitors had been drawn to the recently installed Paul Cummins and Tom Piper piece Poppies: Wave. No doubt attracted in part by the positive media coverage given to the Poppies’ original installation at the Tower of London.

Hopefully, once having seen the Poppies, those visitors then went on to see the other artworks in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Equally, it will be interesting to discover whether the Poppies have had the same effect in Liverpool; installed as they are currently outside St Georges Hall, next to the Walker Gallery and World Museum. Given this position, a work like the Poppies might see more appeal with an older demographic — who make up 17% of the art-going public – who’ll see the piece as part of more established institutions such as the Walker. Or, they may that see it as art, but rather are attracted to it due to the historic context, seeing it as a heritage project.

Using a special piece of art in this way as cultural tourism, one that may have some cultural significance or fame, is one way of attracting people into the gallery, whatever their level of interest is in art. This is a risk; it is uncertain that the audience will stay or return after the exhibition — which attracted them in the first place — has finished. We have to hope that the answer is yes, for that could lead to a change in viewing habits and see people engage in lesser known or challenging artworks.

Here is another possible reason why galleries exist: that they are beneficial to the cultural well-being of people. According to MHM Insights, 11% of visitors across the UK use galleries as a support for informal and formal studies, developing their understanding of art. Galleries often have to strike a delicate balance between curating crowd-pleasing exhibitions, and exhibitions which might appeal to a more dedicated art crowd. Even galleries whose remit is to show newer, more contemporary and previously unknown or unseen artworks and artists still have to attract as many viewers as they can.

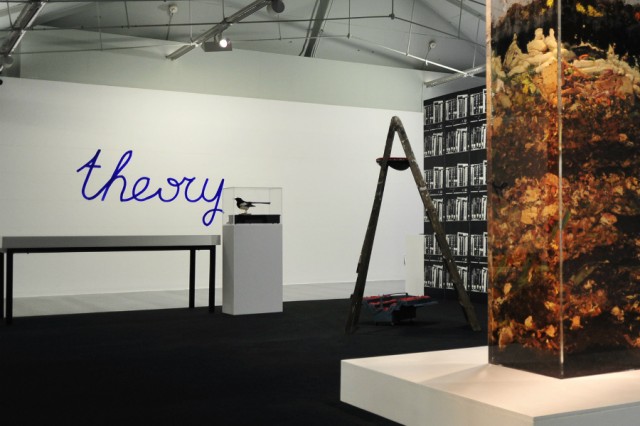

An example: Tate Liverpool’s current Works to Know By Heart season boasts a free Matisse show alongside a more challenging, paid exhibition about a future where all art has been destroyed (An Imagined Museum). Draw them in, then perhaps the audience will engage with much more. Ultimately, galleries exist to engage people with art, allowing and encouraging them to discover art independently.

Once they’re through the door, it is crucial to understand how people in galleries move and behave. Obviously, this changes from person to person and from gallery to gallery. I know from my own experiences, through working in various gallery front-of-house job roles, that the first few moments are spent orienting yourself, looking for clues to show which way to go. At this point, you might be looking for something novel to attract your attention, or that one artwork you’ve heard of or seen before.

How does this initial, welcoming conversation start? Is the duty of the gallery staff or layout, or even the artists, to guide visitors through the world of art? This start or introduction to the gallery may already exist in the form of wall texts or signage, though this will depend on which gallery you are visiting. Again, gallery interpretation is a tricky thing: display too much information and you take away the viewer’s ability to form their own views. Too little, or none at all, and you run the risk of stranding the visitor without a way of navigating themselves through the work on show. This is something that education and marketing departments in galleries lose sleep over.

The danger of interpretation is that you can create a cycle of navigation that goes: art > info panel > art > info panel. There is now a generation of gallery-goers who take part in a cycle of art, info panel, photo (or selfie). By creating this cycle, there is the argument that the gallery is imposing their influence, or an expected mode of behaviour, onto the visitor. Perhaps this isn’t as restrictive or as prescriptive as it seems.

Interpretation points us towards another reason why galleries exist: that they often act as a bridge between the known and the unknown. Though there are points where this fails. One such example was the Bluecoat’s recent Resource exhibition; despite showcasing interesting artworks by the likes of Ben Cain (pictured), Jack Brindley, Jonzo and Laurence Payot, it felt baffling and confusing overall. If an exhibition is a conversation, this felt like walking in halfway through.

Was a lack of interpretation the only reason for a sense of confusion while attending this exhibition? Well, it feels rude to point this out, as contemporary galleries like the Bluecoat exist in order to show examples of the nebulous and fractured nature of contemporary art. This, however, has coincided with a current trend in the UK for exhibitions where the person responsible for organising and delivering exhibitions, the curator, and their concerns, appear to have been imposed in the gallery.

The relationship between curator and artist can inadvertently create a fixed position of what art is, leaving the viewer outside of that conversation. It does make me think about a possible distinction between art viewers. That being, one group goes to see images and ‘stuff’ on the walls, while the other goes to see ‘ideas’… plus stuff on the walls.

Do galleries have a responsibility to engage with people? The short answer is, of course, yes. The primary reason galleries exist is to engage with the viewer, even if the number of viewers is small. There are always factors that affect audience numbers; for example, often artistic activity seems to drop over the summer. Or when a show has a short exhibition run or has a focus on a single discipline.

Often, it is the independent gallery that hosts these exhibitions, and they are not expected to attract huge numbers. Rather, these smaller galleries position themselves within the arts ecology to allow new artists to emerge and experiment along with their peers, providing many artists with the first steps from student to professional artist.

A tall order, maybe, but for art to have a presence in people’s lives it must be visible, available. Only through this availability will there be the possibility of generating more interest in art in many different forms, creating a familiarity. Attracting the five million adults who may not usually approach a gallery doesn’t mean galleries should pander to an idea of sheer popularity; once people are familiar with art in all its forms then they will be more willing to accept more challenging work.

However, I do feel that there remain some fundamental reasons for going out to see art that I haven’t yet mentioned. Speaking personally, I go to exhibitions because I want to learn more about art in whatever form it takes. Equally, I want to be stimulated and engaged by the things I see. The role our galleries play in this is to be open and free allowing everyone access to art, whether they like it or not. Ultimately, galleries only present work. The public’s presence makes it art.

C. James Fagan

This article has been commissioned by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network North West (CVAN NW), as part of a regional critical writing development programme funded by Arts Council England — see more here #writecritical

Images from top: Liverpool Biennial: Claude Parent exhibition at Tate Liverpool; Keywords exhibition at Tate Liverpool, Level four galleries; Poppies, St Georges Hall, Liverpool, photo courtesy James Maloney for the Liverpool Echo; An Imagined Museum exhibition at Tate Liverpool; Ben Cain, Group Work 3 (2015), Resource exhibition at the Bluecoat