In Profile: Stephen King

King of the silver screen? Nik Glover analyses the best-selling novelist’s many triumphs and disasters in book-to-film adaptations, via his relationships with George A. Romero, Stanley Kubrick, Brian De Palma and the rest…

Everyone remembers the sight of Jack Nicholson, wild-eyed and panting, desperately trying to twist a rusted valve in the bowels of the Overlook Hotel, straining every sinew as the pressure gauge on the hotel’s giant old boiler passes into the yellow, into the red, and beyond. Everyone remembers the explosion. Everyone remembers the vision of the hotel collapsing into itself like a wedding cake; Kubrick’s grand allusion to the House of Usher.

Except nobody does. Because when Stanley Kubrick decided to adapt Stephen King’s big-selling third novel The Shining (1980), he took a very Kubrick-esque approach and filleted large chunks of the plot, playing down the overtly supernatural inspiration for Jack Torrance’s descent into madness and re-writing dialogue on the hop, often minutes before filming, leading the movie in entirely different directions to its source material. Few, other than King, would argue that King’s own attempt at filming his novel (for a 1997 miniseries) is an improvement on Kubrick’s masterfully unsettling picture.

From the off, King hated the results, vocally criticising the director for making a picture that played down the pure evil of the Overlook, and for miscasting Jack Nicholson. Speaking to Rolling Stone in 2014, King explained his most recent opinion on the movie:

‘The book is hot, and the movie is cold, the book ends in fire, and the movie in ice. In the book, there’s an actual arc where you see this guy trying to be good, and little by little he moves over to this place where he’s crazy. And as far as I was concerned, when I saw the movie, Jack was crazy from the first scene. I had to keep my mouth shut at the time. It was a screening, and Nicholson was there. But I’m thinking to myself the minute he’s on the screen, ‘Oh, I know this guy. I’ve seen him in five motorcycle movies, where Jack Nicholson played the same part. And it’s so misogynistic.’’

Nothing about King’s experience is unique to the movie adaptation cycle, if we’re to believe various jobbing, albeit highly successful movie writers. Anyone who has read Neil Gaiman’s hilarious The Goldfish Pool will have witnessed the frustration of a talented, self-confident young writer having his work chopped and changed, bastardised and butchered to within an inch of similitude. The Universal horror division of the early 20th Century made two stabs at adapting Edgar Allen Poe’s The Black Cat, neither of which is in any way related to the story. They did the same to The Raven. Fortunately for him, Poe wasn’t around to watch it happen. Why they did it is perfectly straightforward — Horror audiences had heard of Poe, they revered him, so they would go along to see a Universal adaptation of his work. Kubrick picked The Shining out of a pile of fiction, seeing something he would work with.

Today, its author has become the equal of Poe, at least in contemporary notoriety. A hugely flexible writer, the movies shot based on his stories or treatments have included straight horror, prison drama and coming-of-age yarns. More of his novels, short stories and treatments have been adapted into movies than any other modern writer, although there has been a notable drop-off in new adaptations of previously un-filmed works in recent years. Long in gestation has been The Dark Tower series, while the 2013 remake of Carrie did nothing to dim the lustre of Brian De Palma’s shrieking 1976 classic. If King had a cinematic golden period, it was roughly from the release of that movie up to 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption, with honorable mentions for later adaptations The Green Mile (1999) and The Mist (2007) by Frank Darabont, also of Shawshank.

As a newly published author, King appreciated De Palma’s work on Carrie. He praised the artistic integrity the director brought to his story, and its style. De Palma was counted among the New Hollywood field of young, auteur filmmakers that also included Martin Scorcese, Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich, but had lagged behind them in terms of box office pull. Despite respected efforts like Sisters (1973), he had seen close friends including Steven Spielberg step up to a new height of financial success, originating the Summer blockbuster spectacular with Jaws (1975). Carrie didn’t cost a lot to make, and it scored two Academy Award nominations as well as box-office success. The novel climbed up the bestseller lists after the film’s release, rather than the other way around, as would become familiar to its author.

De Palma’s bloody smash cleared the way for King’s second novel Salem’s Lot to be made into a miniseries by Tobe Hooper (not quite fresh off 1974’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) who made a very respectable fist at re-creating King’s vision of a small-town vampire infestation led by the animalistic Kurt Barlow. King considered Hooper to be a genius after his work on Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but would later experience the opposite side of Hooper’s ‘genius’ when the director, somewhat less in demand by this point, made The Mangler in the mid-nineties. While Carrie pulled in critical and commercial acclaim, his novels began to multiply in the bestseller lists.

By the time King began work on Creepshow (1982), he’d had 10 bestsellers, and his personal life was a poorly-disguised mess. A self-diagnosed alcoholic and heavy abuser of cocaine, he would stay up all night drinking and getting strung out, writing two books at a time, getting out of bed early to make breakfast and pack his kids off to school before falling back into the same spiral.

As a young man, King was cursed (or blessed, depending how you look at it) with an inbuilt dread of failure. He would overwork himself to the point of exhaustion, turning to stimulants to prolong his waking hours, to maintain the inner voice that spouted a thick fog of content to be shaped into screenwriting, stories and novels. As he felt himself failing as a writer, he would hit the bottle, and the attendant stress it put on his family life only multiplied his neuroses. In one of his earliest on-screen interviews, for Playboy in 1983, he described the failing early years:

‘The more miserable and inadequate I felt about what I saw as my failure as a writer, the more I’d try to escape into a bottle, which would only exacerbate the domestic stress and make me even more depressed… I’d lie awake at night seeing myself at 50, my hair graying, my jowls thickening, a network of whiskey-ruptured capillaries spiderwebbing across my nose — drinker’s tattoos, we call them in Maine — with a dusty trunkful of unpublished novels rotting in the basement, teaching high school English for the rest of my life and getting off what few literary rocks I had left by advising the student newspaper or maybe teaching a creative writing course…

‘Even though I was only in my mid-20s and rationally realized that there was plenty of time and opportunity ahead, that pressure to break through in my work was building into a kind of psychic crescendo.’

George A. Romero first met King in the run-up to Salem’s Lot, with the idea that the horror icon would direct that for Warner Bros. An established horror icon, Romero was keen to film The Stand, while King pushed The Dead Zone (later to be directed by David Cronenberg in 1983). Romero picked The Stand as his preference, but its post-apocalyptic setting and hefty production cost led them to announce that, to scare up the investment they knew they would need, they would first produce Creepshow, to be written for the screen by King.

Creepshow is a live action compendium piece in the style of The Crypt of Terror, the long-running comic book series which introduced short, horrific stories under a loose overarching framing device, and of which King was an early devotee.

These shorts, themselves influenced by radio serials such as Suspense, were self-enclosed, schlocky little shockers sometimes poorly disguised as morality tales. The stories were incredibly popular following World War II, shifting big numbers and spawning dozens of titles, appealing to the novel post-war social creation: the teenager. The perceived fallout from newly-minted ‘teenage delinquents’ reading these kind of violent and nihilistic comics eventually led to the Comics Code Authority being founded, and the industry finding itself shackled by a new, moralistic code of conduct. At roughly the same time that Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror and Strange Tales were corrupting young minds, the portmanteau horror movie was taking its first steps. Dead of Night (1945) is an Ealing curio, a masterfully tense collection of stories as narrated by the ever-so-posh inhabitants of an English country cottage, who have been visited by a mysterious stranger who claims to be suffering from amnesia. Over the years, many other studios would attempt portmanteau horror, but none with the artistic flair, wit and commitment of Ealing.

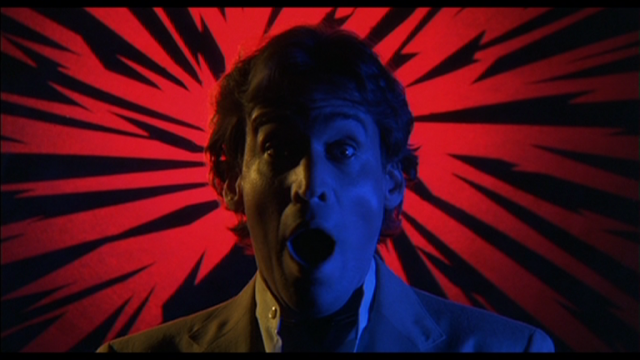

Many portmanteau tales concern a flawed central character who encounters a supernatural or macabre situation and is consumed by it, a motif that would inhabit a selection of King’s most well-known stories, and which would become something of an albatross for him. Creepshow is King paying homage to his early influences, even going so far as to appear himself in The Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill, the pulpy story of a man menaced by a plant-like alien.

When judged against the strongest King adaptations (and more than one can claim to be among the best films ever made in any genre) Creepshow is a minor curio. It’s worth catching to see the man himself getting the chance to inhabit one of his own stories, in a loving homage to the kind of stories that played a formative part in making him the monster he is.

Nik Glover

Cheap Thrills Presents Creepshow (1982) at A Small Cinema, Liverpool, 7-10pm, Thursday 28 January 2016 — £4/5