‘The Invisible Hand’ Of Group Therapy: Mental Distress In A Digital Age

Helping hands, hands to hold, and being in the wrong hands: Deborah Laing finds a reoccurring theme in FACT’s new exhibition about metal distress that leads her into a simultaneously unsettling and empowering environment…

FACT’s new exhibition Group Therapy is all about creativity, energy and engagement: so much energy that even the language describing the artworks spoke volumes — words such as ‘superflex’ and phrases like ‘psychosis sensations’. Would FACT and visiting curator Vanessa Bartlett support the high energy levels I was promised — to lead me by the hand and challenge my perceptions of mental distress?

Entering the gallery on the ground level, I approached what looked like a therapy session: four chairs in a circle with multi-screen options. Titled Twelve (2015), each of the 12 people in Melanie Manchot’s film sequences are in recovery from substance misuse. As she explores their stories and disorders, she takes cares to prevent voyeuristic readings; faces are mostly invisible. Instead, there are repetitive images of hands — hands cutting daisies with scissors, writing on a board, cleaning a tile obsessively; a type of invisible hand, and a metaphor I found to reoccur throughout Group Therapy.

The sentence uttered by one male subject, “I woke up today”, lingered in my mind as I realised that mental distress causes inactivity and that something that seems so natural can become such a difficult act.

With the high level of technology present – including multi-channel video screens, smartphones and tablets – this show is not for the technophobe. Partitioned boxes and internal rooms are scattered randomly, and the negation between the artistic work, movement round the gallery and interpretation left open. This can make the gallery feel in a state of flux; the dialogue between the works developing inner worlds constantly changing as you walk around.

However, this is why Group Therapy is successful in what it sets out to achieve: using stimulating and immersive installations, provocative short films and experimental projects to directly address the experience of mental distress.

The vacuum cleaner’s Madlove experiment (2015) is a case in point: a space in FACT’s foyer where ‘going mad’ is optional. Madlove provides a surrealist environment with Magritte-style umbrellas on the ceiling cradling cloud-projected imagery. Sweet-smelling trellises and gazebos adorned with red plush materials suggest a boudoir; sulking places where the public could explore melancholic experiences.

The vacuum cleaner’s — aka artists, researchers and activists James Leadbitter and Hannah Hull — project is responsible for reconsidering the notion of the asylum and presents us with a responsive environment created by collaborating architects, multi-disciplinary experts and – especially important – the public. This positive act of reaching out reminded me of the film One Flew over the Cuckoos Nest (1975), particularly the stand off between Nurse Ratched’s insensitive view of therapy and the real recovery and hope that McMurphy represents.

Lauren Moffatt’s film Not Eye (2013), funded by the European Commission, is also intriguing. We are presented with a mature woman on a studio set. The visual planes give us an extra viewing dimension; so much so that I raise my hand as images float in front of my eyes, a truly cinematic experience. She relays her anxieties and anger, and her need to hide her face and her eyes from the power of the camera’s gaze. Wearing the 3D glasses provides you with another reading: can the author and onlooker of the subject be mutually compatible?

The train clips in the piece are of particular interest and reminded me of Chris Marker’s photography series Passengers (2011) about a city whose commuters appear trapped in a separate time zone, where unmoving eyes observe a space between time and place.

Kate Owens and Neeta Madahar’s Me and The Black Dog (2015) manages to be highly entertaining whilst carrying a serious message about melancholy. This film is narrated in a fragmented way, so that the central female character poetically describes her relationship and gives us mini scenarios relating to her depression from a young person’s perspective. The dog acts both as a metaphor and apparition. It plays on notions of the shaggy dog story and folklore, including that of mythology; black dogs acting as spiritual guardians and foreboders of death. Winston Churchill referred to his own black dog being a creative force, likewise former and present artists, too many to list.

It can be suggested that mental distress can have roots in the way society is structured; the tools of equilibrium that shroud a capitalist economy. For example, we can all opt in or out of buying a house, as long as the government adheres to low rates and full employment. Disequilibrium triggers panic measures and can cause real pain to some — including unemployment and eviction. The Financial Crisis by Superflex (2009) refers directly to this scenario. The large screen depicts a male figure with a reassuring manner; he asks us to close our eyes. His voice never wavering, the narrator talks us through the action of losing all our material possessions, in order to provide a mental image of how one might feel and cope if none of the material things we aspire to are available to us.

Not a pleasant experience, but one that may get you to think seriously about economic inequality and material loss, and the simultaneous feelings of powerlessness and low self-esteem.

Group Therapy continuously attempts to empower, occasionally encouraging us to contemplate what would happen if mental health support was not there; the invisible hand withdrawing government funds from vital resources. Feeling supported isn’t just about money; it is about emotional support too. Being able to hold a parent’s hand, experiencing friendship and love, holding the hand of a boyfriend… These are experiences we grow up to expect.

Linguistically, we make up adjectives that describe people who support others — a ‘ hired hand’, a ‘helping hand’ — statements that are implicit as well as explicit. We learn to adjust verbs, such as when asked to ‘raise your hand’: these are commands that initiate our need to gain attention but used in the ‘wrong hands’ can render us robotic and unquestioning, like the afore-mentioned Nurse Ratched.

FACT supports the campaigning organisation Mental Awareness and actively promotes creative exchange with therapeutic possibilities through digital art; this is a venue with a conscience, both locally and globally. For example, in the gallery you can play with mobile app In Hand, an anti-psychology programme on preventative measures designed for young people. It picks up negative thoughts then feeds back with positive reinforcements, rather than determining where the negative thoughts originate.

In Hand is available to download and is backed by Mersey Care and app agency Red Ninja. Likewise, the health and well-being initiatives that FACT are commited to is continued in an archive in an upstairs gallery; a ‘helping hand’ providing support and technology to veterans and for those who at some stage in their lives found the invisible hand withdrawn, rendering them homeless or in a mental health hospital.

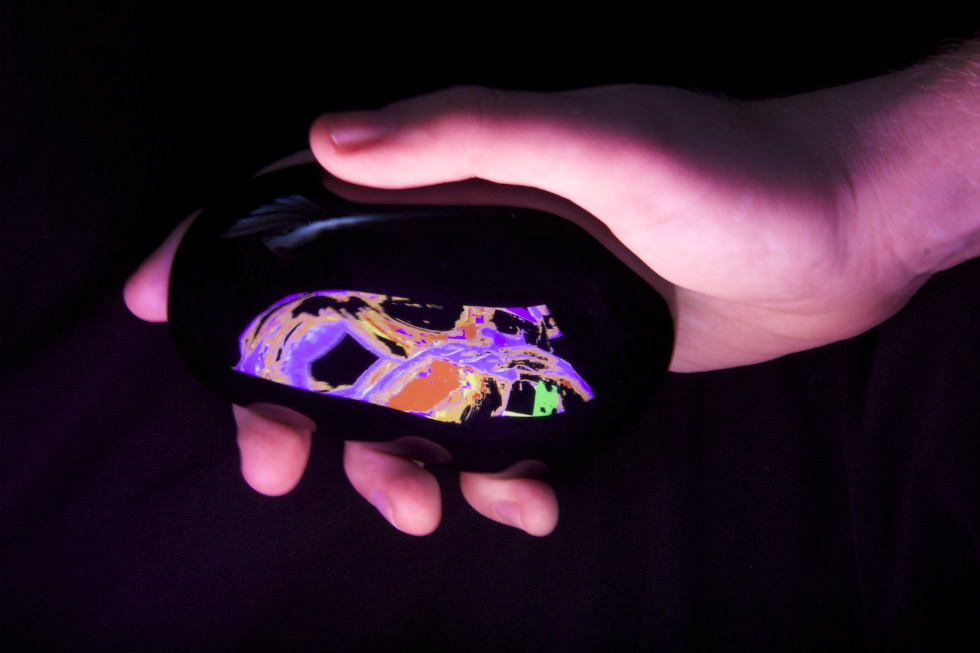

Also upstairs, a large installation Labyrinth Psychotica (2013) – an artist research project by Jennifer Kanary Nikolov(a) — guides you along a ‘single path that twists and turns towards a centre’; a few simple steps towards understanding the subjective experience of psychosis. It is a safe place that ensures our experience is without threat to our own anxieties.

Don’t let the warning signs put you off, unless you really do suffer from claustrophobia or have a history of anxiety attacks. Once again, my hands led the way; the corridors in the maze are narrow, and the navigation difficult. Textures of the material-covered walls alternate; the senses, smells and disorientation are challenging. I begin to panic. I couldn’t find my way out, so ducked under the layers and out of the installation. Leaving, I realised that at one point the Labyrinth and the LED lasers had placed me in another world, cut off from everybody.

Overall, Group Therapy creates situations so that we may reflect on our own mental state, and goes a long way in challenging our perceptions of mental health. It presents us with unsettling situations and supportive, sensory environments that we can inhabit. Maybe you should visit the exhibition with a friend so that you have a hand to hold if needs be.

Deborah Laing

Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age, curated by Vanessa Bartlett and Mike Stubbs, continues at FACT Liverpool until 17 May 2015

Open Tuesday -Sunday, 11am-6pm, free entry