The Big Interview: Joanna Moorhead On Leonora Carrington

Who better to talk about Surrealist painter Leonora Carrington than her cousin, the Guardian’s Joanna Moorhead? Here, Deborah Laing asks the writer about Carrington’s rich and turbulent life, her relationships, and her legacy…

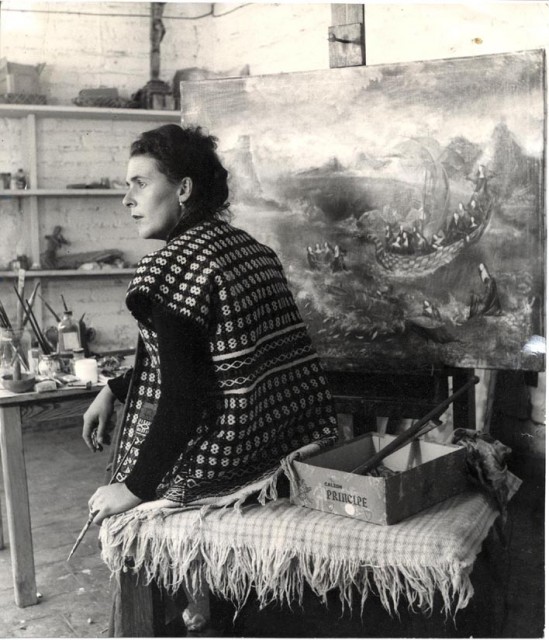

Leonora Carrington, surrealist artist and writer, grew up in a gothic mansion, ran off with Max Ernst and took an epic journey away from a pre-destined debutante existence. With pure determination, she made her way through Europe between World Wars. Young women of her class were often sent to finishing schools in Europe; in Italy, Carrington visited Florence where her love of art developed. But it was in the UK that she fell in love for the first time.

I spoke to Carrington’s cousin, Guardian writer and co-author of Surreal Friends, Joanna Moorhead, about all of these things in addition to her opinions on the artist’s politics and legacy…

The Double Negative: In your article Leonora and Me (the Guardian, January 2007), you describe Leonora Carrington’s time in the UK growing up and indicate that Europe was a turning point in her life. Would you agree?

Joanna Moorhead: At that period in time, wealthy families were educated at home. She had brothers who had already left for boarding school. Leonora until the age of 11 had a governess; she was sent to two boarding schools and was expelled from both. At 15, she went accompanied travelling, to Florence then Paris. This was a big moment in her life: her family was able to support her travels even through the 1930’s economic depression. Young ladies were expected to travel as part of their debutante training. It turned out that the training taught her to become her own woman.

How did the experience of being allowed to travel and pursue her love of art change her?

In her early teenage years, there was a sense of growing dissatisfaction because of the life that was ahead of her; the ‘toff’ or upper-class life didn’t appeal to her. She always knew she was going to get away; everything that happened during and directly after her breakdown suggested she needed to get out, to escape it.

So, in your view, did her class restrict or free her from her status?

Yes and no: yes because she found it a restrictive life, living in a narrow community, not just narrow because of class and expectation though; Leonora was not an aristocrat so was able to form a critical opinion of privilege. My Great Aunt Maurie [Leonora's mother] was adopted and her husband was originally a stationmaster. It was only later, through textiles, that the family made money. They were the ‘nouveau riche’ trying to be what a rich family should be.

You mention Crookhey Hall in Lancashire where she grew up, a grand mansion in a small country village. When you eventually met Leonora for the first time a few years ago in Mexico City, did she talk about the past?

By the time I met Leonora she was an old lady, it left a big mark on her imagination, her memory of it was fading. Understandably, she talked more about her present; it’s through her paintings — particularly her early ones — that the past is captured. I’ve been to Crookhey Hall and seen it for myself. It is dark and huge, foreboding, a heavy house, for myself it’s rather overbearing with a very gothic feeling. At 13, she moved to a house in Silverdale called Hazelnut Hall, a very different house: airy, bright and open, with a view over the sea.

Which of the paintings in her vast body of work depicts Crookhey and the Hazlewood Mansions?

There are a lot of snatches or views of Crookhey in Night Nursery, and Hazelwood in Green Tea. The landscape of Green Tea is very much the landscape of Hazelwood — clipped hedges and preened trees. A self-portrait depicting her in a domestic interior is The Inn Of the Dawn Horse, painted in 1942; I travelled to New York to see that painting but it was also shown in the UK in 2009 in the Angels of Anarchy exhibition in Manchester. That is a really an important painting — it’s who she is. It is accessible to the public because a lot of her painting is very complicated with overlays of aspects of her life.

Once she became a painter in the mid-1930s, she was also in close contact with the surrealist art collector Edward James. How much did patronage play a part in her success?

He bought her painting but didn’t pay her bills, unlike with Dali who was also on his books. He liked her and was impressed,; paintings that he bought for a few hundred dollars he made thousands of pound on later on. He invested well in Leonora. His friendship, for her, was more important than the money. They bonded in Mexico, they had a lot in common, both not quite fitting: they were both eccentric and did not fit in with the aristocratic attitude to other cultures.

Was she a generous and open painter, do you think?

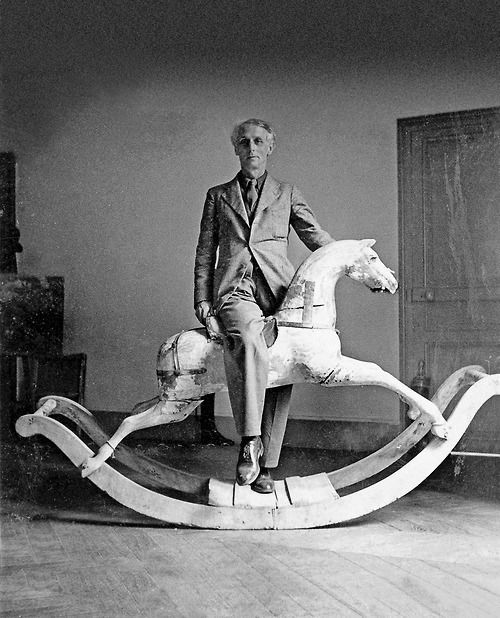

Her paintings are also very truthful, often revealing her inner thoughts on alchemy, mythology, and mystical creatures from her Celtic heritage. The Inn of the Dawn Horse is more straightforward to read: the rocking horse pictured to the right of the painting reoccurs in her life, and my own father remembered the nursery. Also, her and Max Ernst bought a rocking horse when they were in Paris and there’s a photograph of Max Ernst on it. The horse that’s running free beyond the window was her alter ego.

It’s an exiting painting and is a reminder that she can escape at any time, from the painting and from the confines of her class. Her big thing is canvas, borders, the edges, connections — not just a foot in this world but an outer world mirroring the grey areas of life.

Her love affair with Max Ernst — who was seen as a ‘degenerate’ artist in Germany — was relatively short-lived, between 1935 and 1938. Two opposing opinions could be that Ernst’s romantic interest may have either encouraged her awakening as an artist, or alternatively contributed to her short-term mental decline. Which do you think it was?

My understanding of it is the first breakdown occurred in Paris, and then Spain when she fled France. She was taken away to Santander to the sanatorium where terrible things happened to her. The breakdown was definitely triggered by Max Ernst’s imprisonment; taken away by the Vichy French, his absence and the experience was too painful.

Before that awful day, everything Leonora experienced in France with Ernst was beautiful, particularly during 1937: she refers to it as the “honeymoon” of her life. She felt bad when she left the farmhouse they had lived in, and I think she regreted that, but she had to — she was very frightened and young.

How much of the 20-year-old Leonora was aware of the politics at home and in Europe by 1937 — a very turbulent decade?

Ernst was no friend of the Nazi regime. His first Jewish wife whom he lived with in Germany before feeing to Paris died later in a Nazi concentration camp. The war was a real danger in Leonora’s life, the dangers and horrors of it. She was particularly aware in Lisbon; by then she was with her first husband who had helped her from being placed in yet another clinic in Switzerland, a Mexican by the name of Renalto Leduc. Max was already there with Peggy Guggenheim, his third wife, after being saved from a prison camp by friends. At this time, Portugal was neutral, but in 1941 there were real fears that Franco was going to take over and the Nazis would arrive. Nobody knew how it was going to go.

What do you feel is her lasting legacy?

Surrealism in its moment through the ’40s was male dominated. Most people, if you ask them to name surrealist painters, will say Dali, Magritte, Miro, Duchamp (all by the way exiled in New York in 1942). One of the important contributions Leonora made is that she took the idea of surrealism and gave it a female perspective, which makes her a feminist, in a way.

Personally, I know she would not of liked that description of her: she felt strongly that we are conflicting characters. There isn’t a straightforward way of interpreting her work, her instincts were feminist but she would of balked at the idea of a label. I would say that a lot of her attributes were female, and her strongest guiding principle was her instinct.

Deborah Laing

Don’t miss In Conversation About Leonora Carrington, Wednesday 29 April 2015, 6.30-8.30pm at Edge Hill University, FREE (advanced booking recommended). Join Joanna Moorhead as she discusses the life and work of Leonora with Francesco Manacorda, Artistic Director, Tate Liverpool

The Leonora Carrington exhibition continues at Tate Liverpool until 31 May 2015 — Adult £8.80 (without donation £8); concs £6.60 (without donation £6). Included in the ticket cost is entry into the Cathy Wilkes solo exhibition on the same floor

Surreal Friends is available in hardback from Lund Humphries publishing