The Skewed Mirror Of Gretchen Bender

Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman were her peers, but little is known about multimedia artist Gretchen Bender. C. James Fagan visits a new retrospective at Tate Liverpool to explore Bender’s backlash against “immoral consumerism”…

Plato once put forward the concept of the Ideal Form: that within everything is contained the idea of an ‘ideal’ object. In the creation of say, a table, there is a ‘blueprint’ of a perfect table, or something that can be understood as a table, or ‘tableness’.

Bit of fuddle of Plato’s Theory of Forms, but could it be argued that this idea of an ideal form contained within everything created could motivate creative acts. That a pursuit of this ideal keeps the whole human race striving for the better table, the great masterpiece.

All fine when talking about creating or reworking things that physically exist, but what happens when an ideal is based on a fiction? Given we live in the age of mechanical reproduction, with images recreated, reproduced and existing in every corner of life. In print, on screens, on walls.

I’m, of course, referring to the ongoing fiction of advertising and other media. Mostly harmless, right? Just there to tell us we can buy cars, Coke, fridges and beer. Not that the product is the sole thing being sold here; we’re also being sold a lifestyle to go along with it. The message is simple: buy this and things will get better.

And it isn’t solely confined to advertising — film and TV works in a similar fashion. Would the rise of the coffee chain have happened without Friends making hanging out in coffee shops so appealing?

It’s this persuasive presence of media in our lives that is the concern of Gretchen Bender (1951-2004), whose work — alongside Transmitting Andy Warhol — is the new focus of Tate Liverpool’s fourth floor. Along with Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman, Bender was part of a generation that attempted to address the mass media’s use of images to influence, by using the same techniques to subvert and critique the collective consensus, or some would say, hallucination. To make art that would act as a ‘skewed mirror’, as opposed to Warhol’s more celebratory and robotic appropriation of mass media.

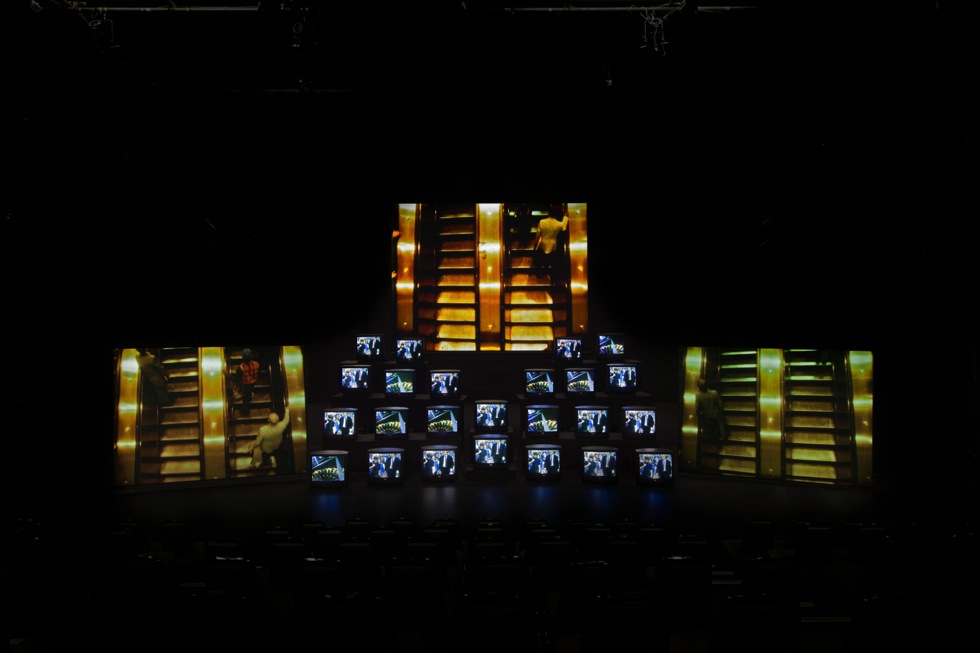

Bender’s huge Total Recall (1987, pictured) installation at Tate takes films, commercials and corporate idents and throws them across 24 TVs and three projector screens. The idea is to bombard the spectator with these images, in a manner similar to the Ludovico technique from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Would it be right to consider Bender’s work as aversion therapy?

Total Recall is there to encourage the viewer to react critically to mass produced images. Like constantly photocopying a picture, eventually the flaws within the original become enlarged, more noticeable and harder to ignore. Bender is engaging in a process which will change the passive nature in which we take in information. This is not merely to say that we allow these images to spill into a liminal mental space, but it is an attempt to re-address the dynamic between spectator and spectacle.

In his essay Ways of Seeing, John Berger describes the viewer as being trapped in a kind of stasis. Within the media world, each advert presents a possible future that is better and brighter than this moment, and is always just ahead. Adverts pass us on the way to this future, leaving the viewer behind. This is the language of the advert, the glamour of the promise, and the illusion of narrative. This was the source which Bender was attempting to use to create a new language, a new set of symbols created from the pre-existing system, but free from the meanings of what Bender termed “immoral consumerism”. A language which would allow the viewer to think critically about the images beamed to them everyday.

Which leads me to an issue I have with Bender’s work: had she selected the right method of broadcast? Can bombarding people already oversaturated with imagery affect them, or does it lead to apathy being piled on apathy? This maybe an unfair critique, as Total Recall was created on the cusp of 24-hour news television and long before YouTube. Before anyone could catch, edit, or repeat films of their own making.

I also have to ask: are the confines of a gallery space the proper venue for this piece? It would seem that its natural home should be outside, or within the media landscape. Where it could be transmitted — a subliminal message to get across Bender’s concept of a new critical language to a wider audience. It feels like the potential of the work can never be reached. Not that this takes away from the experience of Total Recall, the pure experience of being within that layering of sound and vision.

Gretchen Bender’s work still retains real relevance, as the issues she and the other artists of the ‘Pictures Generation’ have yet to be answered; their work swallowed up by the complete world domination of the internet and subsequent insidious reach of social media.

The core question is: will we see artists like Bender emerge from and find the ‘truth’ within the digital domain?

C. James Fagan

Catch the new Gretchen Bender exhibition at Tate Liverpool until 8 February 2015 — tickets include entry into Transmitting Andy Warhol – £8/6