Artefacts, Anarchy & Evolution: Exploring The Serving Library

Currently installed at Tate Liverpool, and both a progression from the traditional public library and a mysterious hybrid of the Internet, Maisie Ridgway evaluates The Serving Library…

In recent years, artists and curators have been met with a challenge: the Internet. The embodiment of anarchy, a portal of free information that slapped the archive in the face the moment it reared its huge, random head. At birth, the Internet brought forth a non-directive, independent and explorative means of learning which, coupled with increasingly results-driven educational institutes, has since led curators and teachers alike to query their role, their methods and, most importantly, their authority.

So, when faced with what might as well be an infinite supply of universally accessible information, how does one present or control it? How can one forge an educational narrative when their own, specialised archives have been engulfed by the astounding content of the Internet? How do those who wish to educate claim back their authority without the power of revelation, now that discovery equates to apathy? Art and more specifically galleries are losing their audience to the Internet. They have two options: evolve or die.

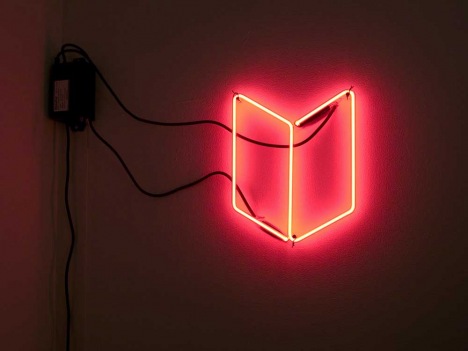

Through the founding of The Serving Library, Stuart Bailey, Angie Keefer and David Reinfort have, albeit reluctantly, undertaken the challenge of the former: evolution. The Serving Library is difficult to grasp. It consists of many disparate elements that developed separately and were then united under one umbrella. Put simply, The Serving Library is a progression from the traditional public library. It allows users to borrow and explore information through four main forms of publication: website, magazine, exhibition and public talks, or workshops. In this respect, The Serving Library appears to be a mysterious hybrid of the Internet and more traditional forms of organised information, like libraries or galleries.

Described as a ‘living document evolving around that which populates it’, The Serving Library undergoes constant transformation as it collects cultural artefacts from its temporary hosts. The aforesaid artefacts are then chosen to accompany or illustrate (or sometimes inspire) texts that form the bulk of the Library. Using their current residency at Tate Liverpool as an example, Bailey and Reinfort chose to present their collection within the skeleton of a former exhibition: an architectural structure built by Claude Parent in the Wolfson Gallery. In doing so, The Serving Library creates another layer of dialogue, as the space itself becomes a point of discussion and education.

Accordingly, it seems that much of The Serving Library’s growth and malleability lies in its lack of an enduring home, although this transience jars with the founders’ ultimate vision of a project that is “absolutely supposed to be permanent”.

Where the project succeeds is in offering a more dynamic and progressive educational option, that challenges the methods in which we currently learn, delivered through an interface that is more structured and selective than the Internet.

However, The Serving Library falls short in its use of an archival system. The archive descends from a place of established patriarchy whereby a ‘legitimate hermeneutic authority’, or archon, filters the archive at his disposition. Bailey, Keefer and Reinfort act as the autocratic archons that filter, control and order their archive according to their preference. Thus, despite the attempts of The Serving Library to award the exploration of the archive to the public, there are inevitable limitations when comparing The Serving Library to the Internet or considering it as a completely radical form of education.

Moreover, in seeking a permanent residence, the project engages in domiciliation, which establishes more firmly its archival status, although permanence could help the project realise its potential to found an alternative educational institution.

Bailey, Keefer and Reinfort do redeem themselves to some extent in their reluctance to fully embrace their archival power, as they refuse responsibility for the political and educational challenges that The Serving Library presents. Bailey asserts that the project “didn’t stem from a conscious ideology” and did not derive from “any sense of sitting down, saying what [they] decided to do, then realising that intention”. Their reluctance to play the ruler demonstrates a conscious or unconscious resistance to the dictatorial history of the archive.

Ultimately, The Serving Library seeks to find a balance between the freedom to explore information according to one’s whim, and the need for some direction in study. It presents itself, rather cautiously, as a possible format for the future of arts education and seems to unite both poles of the learning spectrum: anarchy and structure.

Maisie Ridgway

See The Serving Library at Tate Liverpool until 8 February 2015, free entry

Interested in archive theory? Read Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression