Rust And Bone – Reviewed

DW Mault finds beauty and truth in the existentialism of Rust And Bone…

It seems a perfect time to be discussing the death of Anglo-Saxon narrative cinema, the morning after the announcement of George Lucas selling Lucas Films to the highest bidder. In the 1970s, films a la Jacques Audiard were getting made in Hollywood: films made for and by adults. As opposed to garish action set pieces coalesced together in the hope of selling action figures and some Happy Meals. Films that questioned existential dilemmas: love, sex, death, etc. After the two pronged, double whammy of Star Wars and Jaws, those days were over.

So we look elsewhere, we look as ever to France. So way back, Cinema Francais has always been obsessed with overlooked American cinema; a cinema that attacks our senses, annihilates our sense of good taste and allows us to wallow in the excesses of beasts like effervescent humanity. Hence Jacques Audiard … A man who has done what the numerous English rock ‘n roll bands of the 60s did: sold America’s great idea back to itself as a fresh original genesis story that will be lapped up and acclaimed to the heavens.

One thinks that Jacques Audiard is a man out of time; he makes ungeneric genre films, he shows us opportunists’ malfeasance that exist within internalised testatory fables … and yet he’s an audience pleaser. Anglo-Saxon audiences flock to his films because they are starved of cinema, as opposed to movies or flicks. His films dare you to attempt to eat popcorn, because when you’re there, in the centre of a universe that he has created uniquely for you, you dare not attempt anything, unless it’s emotionally feeling for a bannister to cling on to for dear life.

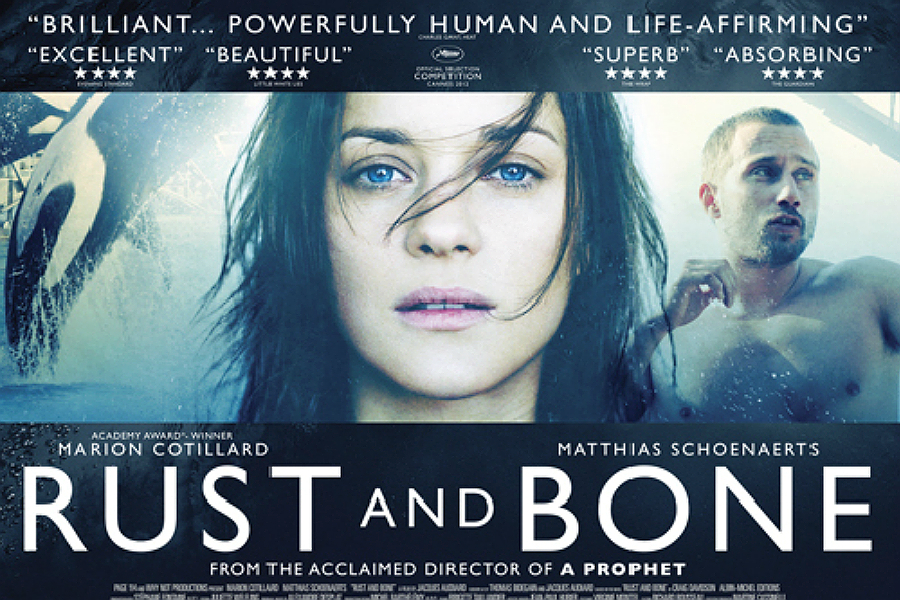

Rust And Bone is Audiard’s follow up to his award winning Un Prophète, and like most great cinema, when you read the plot (that anti-cinematic device that should be banished to wherever George Lucas will be retiring to) it feels/is laughably melodramatic (not in the Douglas Sirk way, more in the Hollyoaks way) and preposterous. A love story between a bare-knuckle street boxer and a woman who trains orca whales and loses her legs after a Seaworld accident. YES REALLY.

Adapted from a series of short stories from Canadian author Craig Davidson, Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), destitute and with his five year old son Sam (Armand Cerdue) in tow, turns up at his estranged sister’s in Antibes. She houses them in her grimy garage, he gets a job as a bouncer in the local nightclub and rescues Stephanie (Marion Cotillard), bloodied after a brawl. They don’t see each other again until after the accident; until after Stephanie has lost both legs to a killer whale. She calls him. He shows her no pity, and from there a relationship develops.

Audiard focuses on the burgeoning relationship between Ali and Stephanie and how positions of power twist, turn and ultimately, change forever. He uses the device of paralleling two characters. One the agreeable societal outlaw, the other the sensitive damaged soul — as Ali, involved in illegal street fighting and surveillance crime, compromises his relationships with Stephanie, his son and his sister. All the while Stephanie begins to find her new identity and gets released back into her life.

Rust And Bone sees the birth of a superstar in the name of Matthias Schoenaerts, who astounded anyone who saw his career-defining role in the Oscar Nominated, Belgian masterpiece, Bullhead. Again he does everything and nothing, like all supreme actors he tells you everything you need to know about his character through a zen-like stillness. A damaged power-keg of a hurt devil-dog-man, who can just about look after himself, let alone a child. Yet his relationship with Sam is believably tough and tender. Dreams became reality when you saw the duo interviewed on the red carpet in Cannes. Armand Cerdue on his shoulders, Schoenaerts was overly protective of the young actor who was fighting sleep all the while trying to take in the experience that is Cannes.

As for Marion Cotillard, she shows the unearned privilege that soars towards and passes arrogance that beauty lies within. The anger and self hatred that lies within that place and says why me, having been chosen with this element that I never asked for, which means I will have to put up with the attention of unwanted idiot men forever and a day – until I lose my legs, of course. Her ultimate empowerment is the moment she discovers the freedom her accident has given her (mentally and sexually) and she has what’s left of her legs tattooed with ‘Droite and Gauche’.

Rust and Bone is corporeal, it shows how nature destroys with one hand after giving with the other. It’s about the delicate body and our arrogance, about control and losing control, and how that is a gift to be accepted with grace. It’s about self denial, self destruction and self hatred, and ultimately it’s about sex and the nature of how we need it and don’t need it. How we want it when we think we don’t, and how we don’t want it when we do. Of course these are all contradictions, like the horrid, messy experience that is existence. Existence that is made immediate and visceral when chosen to fight alone no more.

Another example of Audiard’s total skill (with what Francois Truffaut called ‘the language of cinema’) is his song choices. Who would have thought he could turn Katy Perry’s Fireworks into an explosion of pure emotion? Also you have to love a film that uses Evidently Chickentown.

Since Cannes and LFF there has been a backlash at this film, which I don’t understand, but says a lot about the nature of contemporary Anglo-Saxon film criticism. A world that acclaims the fake pornographic emotion of Beasts Of The Southern Wild but accuses Rust And Bone of being manipulative. Another example of cinema making us take sides. Well I know what side I’m on, do you?

D W Mault

Rust And Bone is screening at FACT from November 2nd and was reviewed at The London Film Festival