Holy Motors – Un Film de Leos Carax

DW Mault finds himself very much at home in the strange and wonderful world of Leos Carax…

Cinema is a home for dreamers, misfits and deadbeats. It’s been 13 long years but Alex Christophe Dupont; perhaps the last of la France profonde is back with a carrion call for cinema in all its majesty. To describe Holy Motors is to somewhat do it a disservice, like art that reaches and tries to sustain, it dies a little when attempting to put it into words (that anti-cinematic device) what you have experienced when leaving the cinema.

Alex Christophe Dupont isn’t his nom de cinema; that would be Leos Carax: an anagram of his first name ‘Alex’, and ‘Oscar’, a reference to the Academy Awards. It can also be read as Le Oscar à X – in English, the Oscar goes to X. As in all of his films, the protagonist is called Alex, and is usually played by Denis Lavant.

Like Godard and Truffaut before him, he was a Cahiers du Cinema critic before making films. He wrapped his first short while still in his teens and a feature-length debut of startling visual and formal maturity, Boy Meets Girl, before turning twenty-four. By the time Mauvais Sang (1986) appeared – a gorgeous, hip, bleeding heart mash-up of noir, sci-fi and boho romance from left of nowhere – his was the uncompromising face of a new French cinema.

It would be five years before Les Amants du Pont Neuf (at that point the most expensive French film ever made) took Carax’s doomed romanticism to operatic highs and cursed him as a Poète maudit, which kind of made his last feature Pola X a fait accompli. Premiered at Cannes and widely attacked, you felt Carax took the insults personally. I remember him at the press conference close to tears just asking to be left alone and to be able to make films.

At the best of times Carax is misunderstood, accused of arrogance; he is quite possibly the shyest man I’ve ever met who fights debilitating depression daily. Therefore, like many before, he escapes to cinema: that darkened room where we go to escape. Which leads us to Holy Motors: acclaimed and detested in equal measure when it was unveiled in Cannes this year.

It is, as with the rest of his oeuvre, steeped in cinema. Whether Griffiths, Cocteau, Muybridge or (don’t laugh) Avatar: Holy Motors is that form that leads us like Dante through a forest we have awoken in towards what we could never have expected. It’s alive with rambunctious cineaste energy, which takes us towards a future that makes us live and begin again and again.

Anglo-Saxon cinema has always struggled with poetry and form against what they prescribe for the world: narrative and superstructure. Introducing André Bazin’s Orson Welles: A Critical View in the late 70s, François Truffaut registered his opinion that “all the difficulties that Orson Welles has encountered with the box office… stem from the fact that he is a film poet. The Hollywood financiers (and, to be fair, the public throughout the world) accept beautiful prose — John Ford, Howard Hawks — or even poetic prose — Hitchcock, Roman Polanski — but have much more difficulty accepting pure poetry, fables, allegories, fairy tales.”

But anyone that understands cinema knows that poetry is cinema and cinema is poetry. Who cares for plot? To misquote CLR James: What do they know of plot who only plot know? Cinema is bigger than story, film is about image and feeling; moments that turn your world upside down. Repeat the mantra after me: “show don’t tell…” This is where Holy Motors comes in.

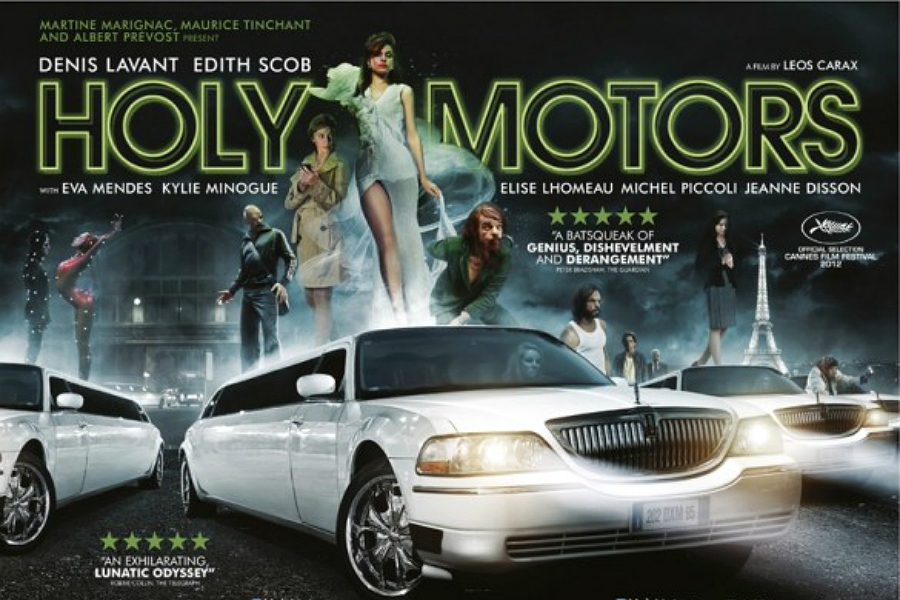

Holy Motors is cinema. It is travel, it is about the fundamental need to change and evolve. It’s about dreams/nightmares and the fear/need of the other that we do not know exists. A man (just like you) gets picked up by a gauche white stretch limousine. It’s driven by a middle aged woman played by Edith Scob: you know from Georges Franju’s Les Yeux Sans Visage. Does that mean anything? The man is called Oscar (natch) and will be taken to 9 appointments where he’ll play various roles.

What those roles are is unimportant for this piece, as you should discover them by osmosis and be shocked, surprised and driven stir crazy. Inbetween this you will question existence and reality vis a vis cinema and the roles we play in life; juxtaposed with the masks we force ourselves to wear.

All this and I haven’t even mentioned the reference to Pixar’s Cars among the ebbs and flows of this very special journey, or Kylie Minogue (she’s there for a short elegiac after-thought).

So go forth and see this experience, this piece of true cinema that takes us from forests of the mind and soul to garages of anthropomorphism to a life affirming intermission that involves churches, running and accordions. Not to mention the greatest physical actor since Chaplin: Denis Lavant. I’m going to go again and again and again… Repeat ad nauseam infinitum.

DW Mault

Holy Motors screens from September 28th