The Art Of Drag: Sasha Velour’s Smoke & Mirrors

“Drag as a state of being.” Verity Reid dives into the visual art inflected world of Sasha Velour, and finds inspiration and non-binary lifestyles in the time of modernism…

The prophetic light-bulb moment in the making of Sasha Velour’s experimental one-woman drag show first materialised on stage, mid-impromptu performance. A twenty-minute hybrid of sporadic lip-synching, silent costume changes and spontaneous queer history titbits – backdropped by the falling apart of her signature high-tech video-projected set – that would become the accidental blueprint for Smoke & Mirrors. Inspired by catastrophe, the souvenir pamphlet elaborates, she envisaged an entire spectacle in which, ‘the audience doesn’t know what’s been planned and what’s real: the audio crashes, cue cards are dropped, the curtain falls, the theatre burns down, the star collapses…’ Besides all of this, of course, is the part where the surprise entrance of a certain Miss ‘Rona sabotages the year of its debut, postponing touring – and life itself.

Casting our minds back to the pre-apocalyptic world, The New York Times described Smoke & Mirrors as “an expressionist performance-art illustration!” and, luckily for Liverpool audiences, the Empire Theatre was home to one of the final shows (just prior to the first lockdown in March, 2020). In thirteen radical acts of authentic self-expression, Velour depicts the story of her life; accompanied by an autobiographical playlist, a (non-malfunctioning) projector, and a lip-synching entourage of surrealistically stylised characters. The most avant-garde of which, are three dancing neoprene sculptures, a glammed-up Nosferatu and a flowering dogwood tree. And not forgetting the self-titled Sexy Ted Talk, in which she defines drag as a state of being that is: “to be seen and for our imagined selves to be seen.” One such self is Alexander Hedges Steinberg, a genderfluid visual artist based in Brooklyn, New York. The city where they founded NightGowns, the drag revue for thinking queens, and Velour: The Drag Magazine – or, ‘a love letter to the art that exists in (and is inspired by) the world of drag.’

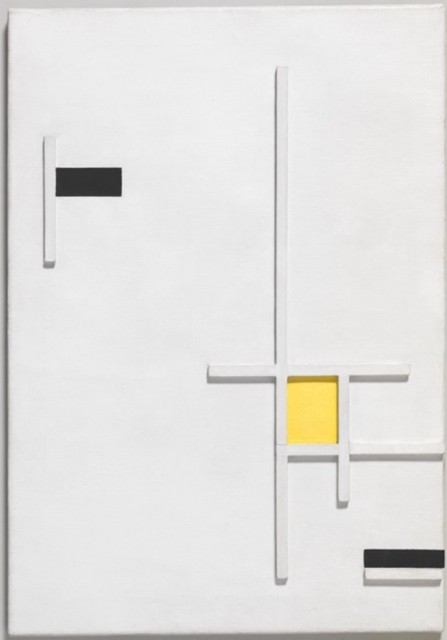

A favourite artwork of Sasha’s – Composition in Yellow, Black and White (1949) – appears superimposed over the canvas of her face in a TateShots documentary filmed in 2019, spotlighting LGBTQ+ icons of the artworld. In a conversation with queer creatives, Velour articulates that what she loves most about the work is that “its subject isn’t a human figure or someone with an identity, but colours and geometry”. Categories that, as a non-binary person, are sometimes far more reliable ones than ‘male’ or ‘female’. “In some ways,” she says, “I can see myself more in a square of yellow than I can in a drawing of a woman or a man.” The painter of said yellow square is Marlow Moss. A radical modernist artist who, one hundred years earlier, rearranged the letters of her former name (Marjorie Jewel Moss) in pursuit of one more befitting a gender-nonconforming nature and androgynous attire.

![]()

Photographed wearing clothes otherwise found in the collective wardrobe of her male contemporaries, she struck an ambiguous figure; with cropped, slicked-back hair, a contemplative gaze and, seemingly, a perpetually half-smoked cigarette in hand. Just as unconventional, were the unorthodox double-lines that appeared in her paintings from 1931. A particular arrangement of things that perplexed the De Stijl movement of the time and its pioneer, Piet Mondrian. Sometime mentor to Moss, Mondrian wrote letters requesting explanations. Initially flummoxed by her theories, the master would soon be introducing the double-line into his own compositions. The pages of his sketchbooks illustrate that he had thought of vertical lines as masculine entities and horizontal ones, feminine; but what she was seeking – in both art and life – as her partner, Antoinette Nijhoff noted in a Stedelijk Museum exhibition catalogue from 1962, was: ‘a line which is not a line, which has neither beginning nor end and which, therefore, does not enclose anything but only indicates relations and offers unlimited opportunities for variation.’

In distinctly Sasha Velourian style (and for those as confused as Mondrian), here we peruse the bookshelf of queer theory in a brief intermission. Turning to page 67 of A Queer Little History of Art, art-historian and activist Alex Pilcher writes that: “A line has no gender. Neither does shape or colour. Gender does not reside in a hairstyle, a name or even a body.” What’s more, the body, outlines gender theorist Judith Butler, in Performative Acts and Gender Constitution, is not a “self-identical” or “factic” materiality, but one that “bears meaning and is fundamentally dramatic”. That is to say: “the body is not merely matter but a continual and incessant materialising of possibilities”, which are to be found in the “arbitrary relation between the stylised repetition of gendered acts through time.”

Speaking of drama and gendered acts through time, the seventh of Sasha’s theatrical performances encapsulates the unpretentious complexity of these ideas in a subversion of the classic turn-of-the-century magic trick – that is, in her words, “dripping with sexism”. Conjuring the ghosts of the vaudevillian illusionists who mystified early twentieth century spectators by distorting the lines of truth and artifice, she embodies both moustached magician and assistant in distress; sawing herself in two with the magic of modern technology. Truth always being at the heart of drag’s artifice, however, a twenty first century audience member can expect not to be fooled, rather delightfully enlightened. At the end of the number (the assistant having miraculously put her body back together), both characters transfigure into one: “I like to destroy any kind of binary that I create about myself”, Velour told Wussy mag.

The real magic of a traditional drag show, she reveals both on stage and in the text of the programme, is that “it’s an illusion, yes, but it’s the kind of illusion that pulls the curtain back on itself”. Behind which, the historically dimorphic categories of gender are revealed to be nothing more than the sleight of a patriarchal hand. The same hand that’s been drawing those binary lines for centuries – the ones that Marlow always knew how to draw better – and betwixt which, exists an infinite space wherein the creation of oneself, or one’s selves, becomes possible. And that, ladies and gentlemen and non-binary beings, is the art of drag. Quoted by memory from Nijhoff, Moss, too, admitted: “I am no painter, I don’t see form, I only see space, movement and light” for, she handwrote in the drafts of her unpublished manuscript entitled Abstract Art (in 1955), “Art is as – Life – forever in the state of Becoming.”

An homage to a square of luminous yellow paint, Smoke & Mirrors is an exhibition of abstract art come to life. The subject(s) of which being: the artist, herself. And in its grand finale, all of Sasha’s imagined selves follow her off-stage in a catwalk of co-existence – each one of them a charming projection of light occupying space beyond the lines of her body, its genetic makeup indistinguishable from that of their photonic colour palette. Though always slightly ajar, The House of Velour’s velvet drapes have yet to open again since the world’s stage began to fall apart; all of us abruptly ushered behind the curtain of human existence and confronted with ourselves. But perhaps, inspired by catastrophe, the future of society might resemble something closer to what Moss spent a lifetime looking for, and what Velour seems to have found in her moving masterpiece.

Verity Reid

This article is part of the series Next Chapter, a new writing project in partnership with Writing on the Wall, to nurture and publish new voices.

Images, from top: Sasha Velour, Smoke & Mirrors; Composition in Yellow, Black and White (1949), Marlow Moss; still of video footage directed by Samuel Douek for Tate Shots (2019)