Piet Mondrian: High Prophet of Modernism

A new exhibition at Madrid’s Reina Sofia puts Piet Mondrian’s contribution to a new art front and centre. Mike Pinnington explores his evolution from Dutch landscape painter to Modernist fulcrum, who perfected composition through colour and line…

To describe Piet Mondrian, the founding father of the De Stijl movement currently celebrated at the Reina Sofia, as a mover and shaker of modernism is something of an understatement. For starters, the pioneering abstract artist called numerous international centres of culture home; from Amsterdam he would move to Paris, then on to London and eventually New York. To the casual observer, it might seem as though Mondrian simply followed his nose, pitching up in cities on the basis of their renown any time he got itchy feet or, perhaps, these decisions were made with a kind of prescience. Both are romantic notions not entirely without foundation but, more often than not, Mondrian’s moves were born of practical necessity; either to avoid looming conflict or due to, as he saw it, a requirement for more fertile ground in the face of scant opportunities to explore progressive art and ideas.

His first significant move, from his home in the Netherlands to Paris in 1911, was one marked by personal and professional change. He left behind a fiancée and dropped the second ‘a’ from the original spelling of Mondriaan; a shedding of the life he had known and signal of intent. Proving this was more than superficial gesture, his work would also be subject to transformation. Prior to becoming a byword for and champion of abstraction, Mondrian had forged a successful commercial career as a figurative painter.

To chart his evolution and then revolution, we need look no further than Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque (also in Paris, the city of modernity, at this time). Their experiments in cubism – fragmenting and abstracting people and objects – astonished Mondrian, inspiring him to leave behind or rework realist paintings. One such work was The Tree A, completed in 1913, which he adapted so that all that was left of its trunk and branches was a network of lines. Fully embracing these new methodologies, he said “I want to come as close as possible to the truth, and abstract everything from that until I reach the foundation of things”.

In Paris, then, Mondrian took his first steps into a larger world, steps that would ultimately lead to his work being so widely recognised and celebrated today. Shortly after this profound awakening, however, a visit home to see his father in 1914 coincided with the outbreak of the First World War, forcing him to remain in the Netherlands. Despite this unforeseen extended period of exile, Mondrian found ways to continue his journey – at least stylistically if not literally. He met fellow Dutchmen Bart van der Leck and Theo van Doesburg in quick succession.

Both proved pivotal. Van der Leck’s use of vibrant, primary colours had an undeniable influence on Mondrian, while Van Doesburg brought greater focus still to his practice, eventually leading to their co-founding of the magazine, De Stijl (‘the style’), which shortly became a movement. In its pages, Mondrian explored his ideas on art, and if he had initially felt chastened by his unplanned home leave, it pushed and inspired him to develop new thinking. For him, cubism hadn’t gone far enough, and he argued that Picasso had failed to follow through on the abstract implications of his work.

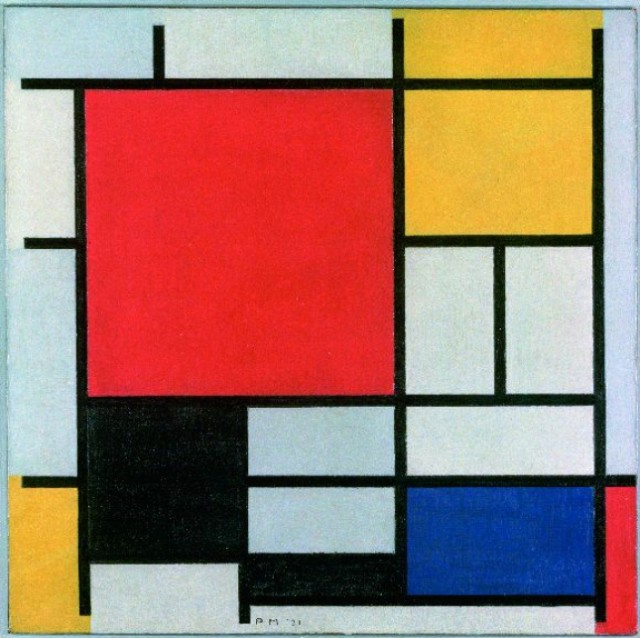

With the war over, by 1919 it was possible to return to Paris and to his home/studio at 26 Rue du Départ in the city’s Montparnasse district. It was here that Mondrian began to produce the paintings that we now most associate with his name, those strictly comprised of planes of red, yellow and blue against a grid of black and white (an ultimate invocation of his geometric abstraction that would come to be universally known as Neoplasticism). “Art is higher than reality”, he said, “and has no direct relation to reality. To approach the spiritual in art, one will make as little use as possible of reality, because reality is opposed to the spiritual. We find ourselves in the presence of an abstract art. Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man.”

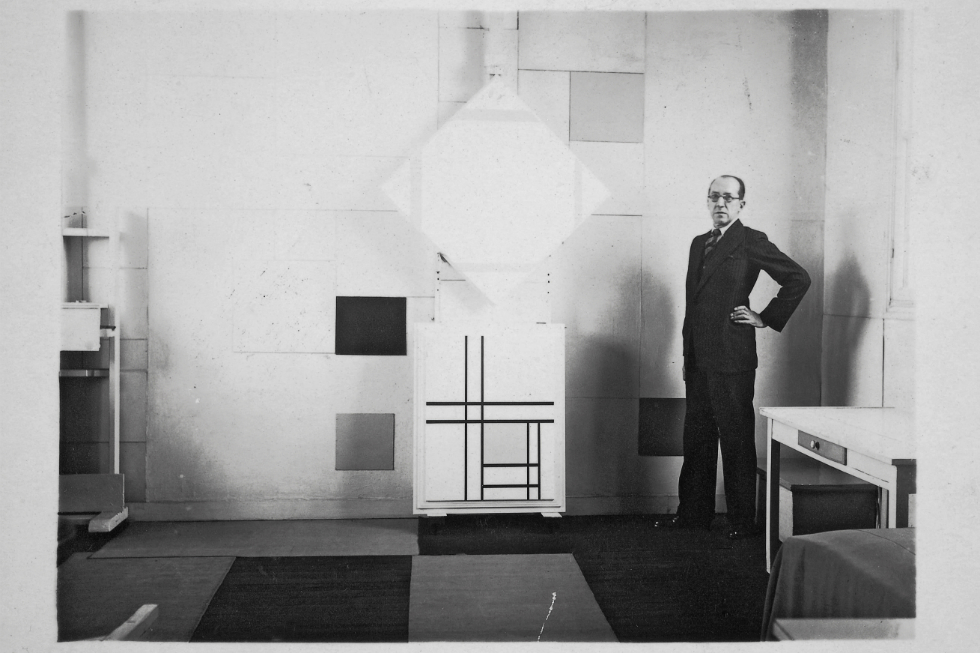

His art seeped into and transformed his studio, making of it a three dimensional artwork in which he placed moveable colour panels over the walls. Art historian Yve-Alain Bois described Mondrian’s studio as “an experimental expansion of the work and the condition for its accomplishment.” His friend and regular visitor Maude van Loon said “The front door was nothing special; just a wooden door. Between the front door and the studio there was a little vestibule and a dark corridor. Then you went through his door and suddenly there was a marvellous white studio with a colour plane here and there. It was like stepping into paradise…”

Following another move to a new studio in Paris in 1936, however, a failure of geopolitics once again intervened. This time the threat of the impending Second World War led Mondrian to enquire among his contacts about a move to London. Though not insignificant, his stay there proved brief (1938-1940), with Germany’s further encroachment into Europe causing him to curtail his time at Belsize Park in a studio near his friend and admirer Ben Nicholson. His subsequent move to New York would be the last great adventure for the pioneering artist; now in his late 60s, Mondrian still had time to embrace another movement, as he welcomed the influence of jazz, boogie-woogie in-particular, into his practice.

The genre lent its name – and syncopated rhythms – to his final works: Broadway Boogie Woogie of 1942-43, and, in the year of his death, the never-to-be-completed Victory Boogie Woogie (1944). The paintings, with their bustling colour and suggestions of traffic on New York’s streets, signalled there was more to come from Mondrian, an artist whose influence continues to echo and inspire today – in the worlds of art, design, and popular culture.

Mike Pinnington

Mondrian and De Stijl continues at Reina Sofia in Madrid until 1 March

Further Reading: The New Art The New Life: Piet Mondrian Examined

Images: Mondrian in his Paris studio in 1933 with Lozenge Composition with Four Yellow Lines, 1933 and Composition with Double Lines and Yellow, 1933. Photo by Charles Karsten; Piet Mondrian, The Tree A c.1913; Piet Mondrian No. VI/Composition No. II 1920