“What is he looking at?” John Stezaker’s Untitled 1978-9

The celebrated collage artist makes a trap for the gaze, finds Mike Pinnington; epitomising the pleasure of looking. But just what — or who — is he looking at?

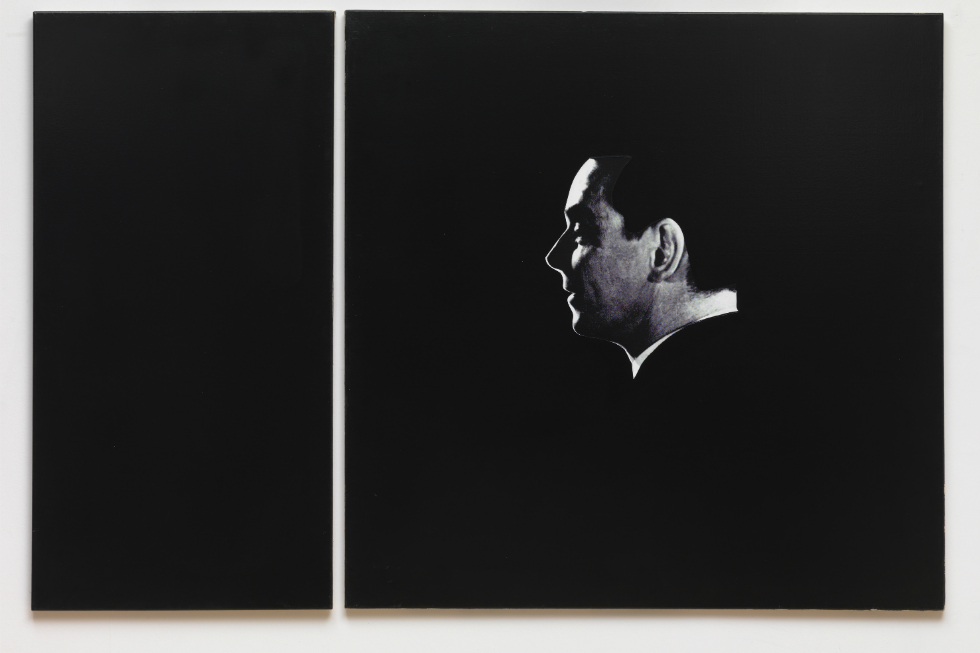

What is he looking at, the man in John Stezaker’s silkscreen work in the second floor Constellations display at Tate Liverpool? A lover, friends; simply the view from his apartment window perhaps? The expression on his face seems affable, amused. Beyond this, however, we are reduced to guesswork; the picture (like a jigsaw puzzle with an important piece missing) feels tantalisingly incomplete. In much the same way that our mystery man’s head is isolated against the black monochrome of the canvas, Stezaker leaves us hanging, with more questions than answers, denying us narrative closure.

There is also the fact that the work is presented in two parts. This device, creating what the artist has described as “a trap for the gaze”, eschews any final destination for the man’s line of sight, meaning the inquisitive are going to have to work for their answers.

Certainly, there are enough clues for curiosity to be piqued, and the display caption provides numerous breadcrumb-like leads. It tells us, for example, that the source material for this image was “an Italian magazine that used photographs and a comic-strip format to present romantic stories”.

So, what’s missing from that second panel that may have been in the original?

That this character has been appropriated from romance certainly supports the idea that the object of the gaze is indeed a lover – or a potential one, at least. In denying us narrative convention – seeing what he sees – we are also being asked to think about why that might be, meaning that Stezaker’s “trap for the gaze” doubles as a space in which to draw our own conclusions. It’s safe to assume I think that, in the original story, the object of his affection would have been a woman; the viewer encouraged to see her, vicariously, through our romantic lead’s eyes.

This gentle provocation by way of open question from Stezaker recalls film theorist Laura Mulvey’s ground-breaking theories around the “male gaze” (Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema 1975), related to what Freud called “scopophilia”, or the pleasure of looking. In engaging with a narrative, she argued, we develop a relationship with what we are watching, taking “a pleasure in looking” split between the active male character and the passive female, on screen merely to satisfy the role of object of desire. Stezaker, a student of the Freudian philosopher Richard Wollheim while at London’s Slade School of Fine Art in the 60s, had made similar observations.

Interviewed by Michael Bracewell for Frieze magazine’s March 2005 issue, speaking about his early career, Stezaker said that a key question for him to resolve was “how can you be an artist in a culture of images?” Of course, he wasn’t the first artist coming to terms with multimedia. Before him, Francis Bacon responded by focusing on depicting psychology and the human condition, often working from photographs and film stills. Maria Lassnig, meanwhile (who rarely drew inspiration from existing imagery), used the canvas to expose what a camera couldn’t – how (and what) she literally felt, and Ella Kruglyanskaya, whose work is often laced with visual puns and inferences, creating a wry ironic distance, often playfully satirizes gendered expectations to challenge conventions of (female) representation.

It is hard to imagine Stezaker’s question going away; far from it. In an era where access to images is only a click of the mouse away, today’s artists – Kruglyanskaya included – wrestle with its implications, which continue to blur, adapt and multiply with successive generations of new media. The response in the hands of artists, only some of which I’ve discussed here, continues to fascinate.

Mike Pinnington

This essay is taken from Tate Liverpool’s new seasonal publication Compass. Available for £1, exclusively at Tate Liverpool, it features articles and essays exploring exhibitions on each floor of the gallery. Find out more information about Compass here

John Stezaker, born 1949 Untitled 1978-9. Silkscreen and acrylic paint on 2 canvases 1220 x 1865 mm. Purchased 2012. © John Stezaker. Image courtesy Tate. This work forms part of the free Constellations displays on the first and second floors of Tate Liverpool: Highlights from the Nation’s Collection of Modern Art (ongoing)