The Scammers Become The Scammed: I Must First Apologise… — Reviewed

By mapping the contours of something so commonplace as a junk email, Orla Foster discovers, artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige remind us of the hidden depths that may be beneath the surface of any story…

There are few technological entities more maligned than the spam email. Long and rambling, sycophantic and immediately discarded, they nevertheless have held a long fascination for Beirut-based artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige. Having built up an archive of more than 4,000 junk emails, the pair decided to construct a “genealogy of online scamming” for I Must First Apologise…: an exhibition at Home art space (Manchester) which questions the motives behind the stories people tell about themselves, and the process by which those stories are transmitted across the internet to total strangers.

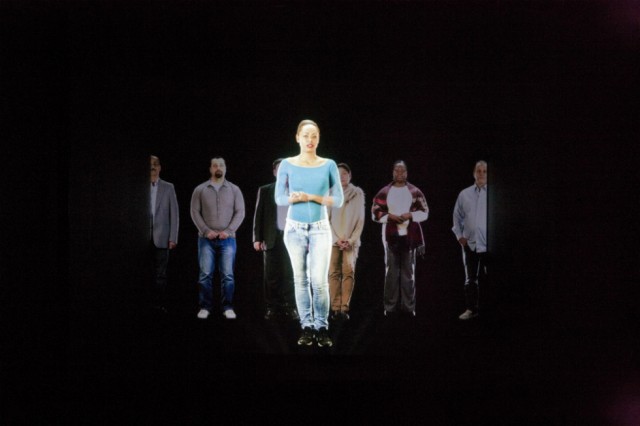

First among the works is The Rumour Of The World, a sprawling video installation made up of 38 different monologues. The room, illuminated solely by television screens, is a cacophony of different voices clamouring for attention; it’s only when you stand directly in front of a monitor, eye to eye with the speaker, that the noise fades out and you can finally hear the details of each individual story. Presented in this format, the hoax emails shift to become testimonies, with each speaker recounting what appear to be personal struggles and hardships. Nevertheless, they all end the same way: by asking for large sums of money.

In the next room, the source texts themselves are gathered for the visitor’s perusal, compiled in a vast white tome — this is the Scams Atlas. We are all familiar with the tone of such emails, to the point that we barely register the details. A butler in Mosul begs for money to leave Iraq following his employer’s death. A Hong Kong banker invites the recipient to register as next of kin of a dead aristocrat and become heir to his unclaimed fortunes. The tropes are so familiar that they often don’t even make it to the recipient, the emails marked as ‘trash’ before they can be opened. Yet these are still narratives which demand the reader to suspend their disbelief, if only for a moment. Packaging them as a volume, on paper as tissue-thin as the pages of a bible, gives them a timeworn quality, far surpassing their original worth.

Directly opposite, (De)synchronicity is a tableau of videos showing four different internet cafés in Lebanon. Actors flit between each site, supposedly constructing scams, yet never escaping the confines of their own surveillance-riddled, claustrophobic environment. The piece contradicts the idea of scammers having any mobility and presents them as being confined instead to their immediate surroundings. If online swindles can offer up an escape route, then this one is a cul-de-sac.

Meanwhile, The Trophy Room explores scamming’s strange offshoot: scam-baiting, the practice of wasting a scammer’s time by engaging in a prolonged dialogue with them. Simply by responding to the initial email, the scam-baiters enter into a bizarre relationship with the scammer, wherein the roles are reversed. No longer is the recipient a victim blindly offering up their bank details, but a negotiator, demanding constant ‘proof’ of the scammer’s veracity, and on very specific terms.

At its most extreme, this can involve the scammer performing rituals at the scam-baiter’s request, which if carried out are published as ‘trophies’, many of which are reproduced here. One scam-baiter, Nurse Nasty, posts a set of instructions urging the scammer to photograph himself in various pornographic poses. Another, under the alias Rumbero, triumphantly shares photos of his ‘pet’ crouching shirtless and surrounded by candles inside what is described as a ‘circle of power’. Copies of these exchanges are presented to the visitor on long scrolls in the gallery, almost as if they had been carefully passed down through the centuries.

The trophies themselves, presented in sleek glass displays, are like digital relics, tokens of revenge against the robbery that might have been committed in their place. Yet for all the vigilante intentions behind each trophy, the effect is incredibly sinister; a web of manipulation and duplicity that simply couldn’t have existed prior to the internet. How is it possible to drive another person to carry out your every whim, without ever stepping out from the anonymity of a computer screen?

This catalogue of humiliations recasts the scammers as gullible clowns readily beaten at their own game. Yet this is obviously not always the case — people still fall for online hoaxes and are cheated out of a lot of money as a result. How exactly does it work? In a piece titled Fidel, one of the actors featured in The Rumour Of The World talks the viewer through the process of scamming as a professional vocation. This time it is not simply a choreographed performance, but a candid account drawn from his own experience.

Fidel explains that scammers are prepared to employ any means possible to track down their victim, regardless of the language they speak or where they live, and will travel across continents to orchestrate each step of their plan. “Every move will have to keep the victim in suspense,” he reflects. “It’s another kind of movie.”

It’s interesting that Fidel uses the word ‘movie’, as a major theme of the exhibition is that of fiction and distinguishing between the varying truths that can be projected about the same subject. Just as Fidel talks about the scammers questioning the reality of their targets, we are also left trying to piece together the conflicting narratives in the gallery. The fact that we see some of the actors appear in more than one video can disorientate the viewer, muddying our grasp on what is real and what is constructed. When are the speakers accounting for their own experience, and when are they simply characters reciting their lines?

The videos compiled in It’s All Real are, as the title suggests, more revealing; in particular, Omar And Younes, a short film portrait in which two young men talk about their experiences growing up as undocumented immigrants in Syria and Lebanon. Both have African fathers, and reflect on how this has, at times, made them feel like outsiders in the Middle East, a status further compounded by not holding the correct paperwork. It’s a highly personal account, with both men sharing anecdotes about their families, holding up childhood photographs to the camera to explain their significance and focusing on small, idiosyncratic memories. For one snapshot, Omar smiles as he recalls deliberately popping his eyes open, in a conscious effort to avoid blinking.

As with the chorus of narrators in The Rumour Of The World, the subjects both gaze intently into the lens, as if they are defying the viewer to pick holes in their story. Yet this time, the experiences being related are true. There is no superlative language, and no supplicatory footnote asking for cash. Instead, each admits to feeling trapped within the borders of their respective neighbourhoods, with nothing to do and no way of escaping. They do not attempt to coax strangers to help them, nor do they have a cross-continental network of accomplices to collaborate with.

This piece is more typical of Hadjithomas and Joreige’s earlier output, which tends to focus on the disorientation of living in post-war Beirut, as well as the desire to use personal images to reconstruct a city in the wake of destruction (one 2003 work, Lasting Images, is a three minute reel of film footage shot by Joreige’s uncle prior to his abduction during the civil war). Even so, Omar and Younes’ stories can still only be accessed through the filter of the artists, making them, paradoxically, just remote to us as those detailed in the junk emails.

The overarching theme of I Must First Apologise…, then, is that of interpretation; the disorientating nature of online correspondence, and the compulsion to put a human face, or simply a mask, on the unknown. By mapping the contours of something so commonplace as a junk email, the artists remind us of the hidden depths that may be beneath the surface of any story, while acknowledging that, ultimately, the ‘truth’ remains out of our grasp.

Orla Foster

This article has been commissioned by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network North West (CVAN NW), as part of a regional critical writing development programme funded by Arts Council England — see more here #writecritical

See Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige: I Must First Apologise… at Home, Manchester, from now until Sun 1 Nov 2015

Images, from top to bottom: The Trophy Room; A Letter Can Always Reach; Fidel. Courtesy the artists and Home