What Is Art School For?

As questions about contemporary art education abound — from the Houses of Parliament to artists’ studios — Liz Mitchell asked key art school representatives across the UK what they thought. The response was an unexpectedly impassioned debate, centred primarily on the concept of curiosity…

“You may think

That the Art College is very free and easy. But it is not.”

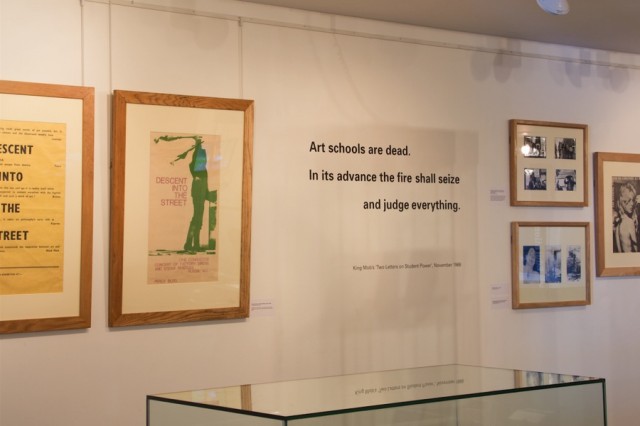

This statement was made nearly 50 years ago, by the Association of Members of Hornsey College of Art (1968). Earlier this year, it appeared in big vinyl lettering on a gallery wall at Manchester School of Art. I saw it in July, reviewing the exhibition We Want People Who Can Draw, and it has stayed with me ever since. The new academic year is just beginning at Manchester and with it, my second year teaching Contextualising Practice. The task is challenging and rewarding in equal measure; I am an art historian/curator by training, not a teacher or even an art practitioner. But since embarking on a part-time PhD three years ago, the art school has slowly seeped into my system. And with it, a question: what exactly is art school for?

We Want People Who Can Draw was organised by a small group of research students and lecturers. Its main audience was other students and lecturers. Its content included posters, pamphlets and ephemera that documented the unfolding of political activism in the art school during the 1960s and ‘70s. But the exhibition was not just a historical essay. Its curators were posing a challenge to the contemporary art school. In a world where education has become a product to be sold, where students are regarded as customers and learning is parcelled up into discrete units measured by commercial transferability, what kind of place has the art school become? And what is art education for?

In May 2013, a conference entitled Whats the point of art school? at Central Saint Martins (University of the Arts London) addressed some of these questions. In the panel discussion at the end of the day, Professor Ute Meta Bauer, Dean of Fine Art at the Royal College of Art, answered the question by suggesting that if you don’t need a degree then don’t spend the money on one. Go to free lectures (there are lots out there), club together with like-minded people and spend the tuition fee renting a studio instead. She talked about the critical importance of art education as a space for free thinking, for learning how to fail, how to ‘not-know’, where outcomes are not predetermined before you even begin. And how a culture of targets and recruitment drives and crippling tuition fees is killing this. A senior figure from the most prestigious art school in the country was advocating not going to art school. Provocative, but I’m not sure how helpful this is for the thousands of students enrolling this week.

In his introduction to 101 Things to Learn in Art School (2011), Kit White says: “Lessons learned in pursuit of art are lessons that pertain to almost everything we experience. Art is not separate from life; it is the very description of the lives we lead”. In the afore-mentioned Central Saint Martins panel, artist Bob and Roberta Smith described art as participation, association, creative thinking — essential qualities for a democratic society. But as art is systematically downgraded in schools (the Warwick Commission report this year revealed a 50% drop in GCSE numbers for Design and Technology and 25% in arts-related subjects since 2003) and tuition fees further narrow the field of opportunity, Smith argues, the art school runs the risk of becoming so elitist it loses its point.

25 years ago I opted for an ‘academic’ degree rather than art school. I compromised by doing History of Art, up the road at the ‘other’ university. A familiar story back then — you didn’t do art if you could get the grades in other subjects. I’ve worked around art and artists all my life, as a curator and writer. And now, in my 40s, I’ve finally done it — I’ve gone to art school. In some ways it does feel free and easy, especially after life in the nine-to-five working world. But the Hornsey students were right. It’s not. It’s deeply, seriously important, in ways that aren’t quantifiable by market measures. A student friend mentioned to me recently that he knew a guy who’d failed his art degree at Manchester, but who firmly believed that his art school experience continued to influence all his thoughts and actions. I’m not advocating failing your degree, but clearly, art school is about much more than something for your CV.

In reviewing We Want People Who Can Draw, I emailed the exhibition’s curators, along with a few friends and colleagues, to ask them: what do you think art school is for? This rather casually asked question sparked an unexpectedly impassioned debate, one that centred primarily on the concept of curiosity.

The dictionary defines curiosity as “a strong desire to know or learn something”. But this isn’t really good enough. Curiosity feels more like a kind of momentary stoppage caused by unexpected observation. Being curious is a state applicable to both subject and object — I am curious to know more about this curious thing. But it is easily dismissed; when quizzed as to why we ask particular questions, we might answer: “Oh, just curious”, as if it doesn’t matter. Professor in Art Education and Art History at the University of North Texas (USA), Tyson E Lewis, argues that ‘just’ is a way of disavowing this stoppage, what he describes as the appearance of “a surplus in the field of the sensible”. The curious is something that doesn’t quite fit; curiosity is our recognition of this. French philosopher Jacques Rancière describes curiosity in terms of looking where you are not meant to look, and asking questions that are not your questions. This is paying attention to the moment of stoppage, and following it up. It is curiosity as not knowing your place — or maybe knowing it very well but choosing not to stay in it. Which locates it as a potentially transformative state of being. Following Rancière, Simon Faulkner, Senior Lecturer in Art History at Manchester School of Art, described his ideal of the art school as:

“…a place where the relationship between learning and its effects is not predetermined. Art school education should be something through which new questions are asked and new possibilities are opened up, including questions about how art education might be experienced and what it is meant to do.”

So maybe art school is not ‘just’ about being curious, but about understanding the implications and responsibilities of curiosity. About becoming attentive to those moments of disruption that shift the parameters of what is reasonable or even possible. Juan Cruz, Dean of the School of Fine Art at the Royal College of Art (London), describes his job as: “helping students to gain some sense of their own criticality and agency… to acknowledge and exploit the fact that they are cognisant beings capable of making decisions and susceptible to wondering about where that capacity comes from.”

Cruz is also a participant in The Autonomy Project, a European partnership of art institutions set up to develop and critique the concept of autonomy in contemporary artistic and curatorial practice. Autonomy is a key concept in the production of art. Once it meant the conscious separation of art and the artist from the social conditions within which work is produced. Art that was self-referential, free-floating, released from the concerns of everyday life — modernist art. The Autonomy Project doesn’t mean it like this. We live in a world now where it can be argued that all action, all meaning exists only within the social, political, cultural and economic conditions which make it possible. In this context, art is always already mired in the ideologies from which it emerges. This, in part, lay behind the protests of the 1960s and ‘70s. Art should be about society, of society, within society.

The Autonomy Project thus seeks a different understanding of what an autonomous art practice might look like. It seeks a way of producing socially engaged art, an art that does something whilst recognising that it doesn’t do it from ‘the outside’. Art that is also aware of the way in which everything we do is co-opted, re-interpreted and assimilated back into the society that produces it. Which is how the bad girls and boys of contemporary art command the highest prices in our novelty-craving, market-driven world. Jeroen Boomgard, another contributor to The Autonomy Project, describes the purpose of art education as making students aware of this contradictory demand to obey by disobeying:

“This awareness cannot be attained by teaching them to ‘do their own thing’ but by teaching them to ‘do their thing’ in relation to the specific ways in which art is instrumentalised at any given time and the specific ways in which it is supposed to refuse this very instrumentalisation.”

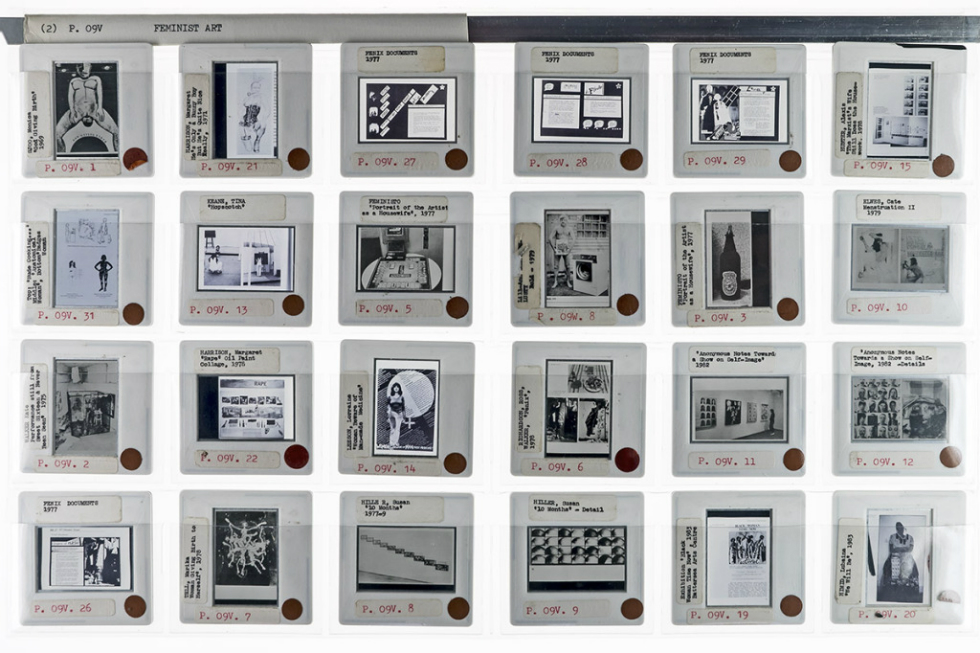

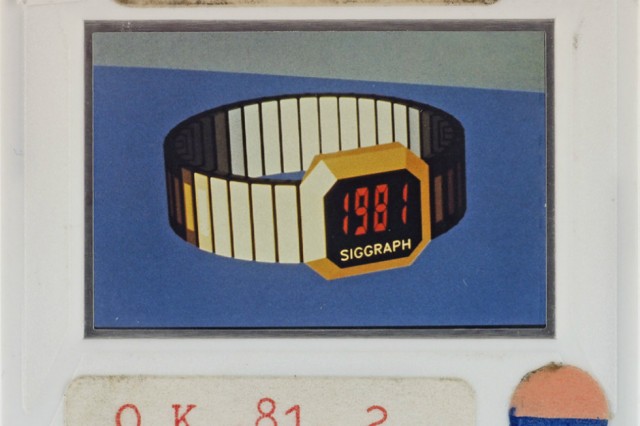

Towards the end of last term, I became involved in a project to save Manchester School of Art’s historic Visual Resources Centre. The Centre is home to a collection of over 300,000 slides, from lantern slides of drawing classes in 1910 to teaching aids from the ‘60s onwards, and the documentation of degree shows a decade ago. It is a visual and material history of British art education. But, as has happened in so many areas, it only took a few short years for the ubiquity of the digital to render it obsolete. So earlier this year the art school decided to digitise a small number of images (those for which the university owns the copyright) and dispose of the rest. After all, without the potential of income-generation, what possible use could it be?

In response, a small group of students set up a ‘participatory artwork’, making use of the very digital medium that had de-valued the collection, to explore different notions of value that it might yet embody. Adopt a Slide invited students, staff and anyone with an interest, to visit the collection, select just one slide and ‘adopt’ it, by means of creative response and writing, shared via a blog, pickaslide.wordpress.com. The response was immediate, impassioned and, on occasion, blunt in its condemnation of what one participant described as ‘the econometrics of the art school’:

“Walk the corridors of art schools up and down the Kingdom and you see one shiny Mac suite after another, distinguishable from each other only by their differing appeals to weary blandness… In this way, art schools have increasing needs for huge portico lettering, because once inside you can’t tell them from the business and enterprise academy.”

Contributions to the project ranged from the lyrical and reflective to the stridently political — and sometimes both. They reflect the diversity of the collection and its potential for sparking discussion and ideas. On the project blog, ‘computer art’ from 1981 sits alongside casts of Greek statuary from the 1900s; Nigerian figure painting, once filed under the heading of ‘Ethnic Art’, alongside Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ. Reader in Art Fionna Barber adopted a whole sheet of slides bearing images of feminist artworks by the likes of Monica Sjoo, Margaret Harrison and Lubaina Himid. In her accompanying text she reflects on her excitement at discovering these artists as a student, and how she later used these same images to give her own students a sense of how art practice might connect to a wider politics:

“The slides on this sheet speak to each other… And this multiplicity of images and the politics that impel them also evokes an important feature of feminist art practice in the 1970s and early ’80s. This was about strength and solidarity as part of a collective politics…”

Three months on, a ‘curious’ thing has happened. The diminutive analogue slide, with its transient, apparently worthless image thrown against a painted wall, has become a site of resistance. Resistance to the concept of value measured purely as market worth. Its very obsolescence, an odd combination of durability and vulnerability, opened up a range of unexpected possibilities and spaces for debate. This is exactly what art school should be doing, facilitating the chance encounter and proliferation of ideas. But in this case, the space opened up was one of challenge to the very institution that houses it.

Framing Adopt a Slide as an artwork was both a conceptual and political strategy. In another context, it might have been conceived of simply as a campaign. But it’s harder to interfere with the integrity of an artwork than it is to question the legitimacy of protest, particularly in the very place of art production. And anyway, as we know, protest is fine if it’s art. However, it was (and is) more than a cynical gesture. Another of the project collaborators described it thus:

“A set of instructions that sets a frame that then builds a thing…The ‘thing’ becomes something more than all the voices together. The art work frame makes us think of the ’thing’ in a poetic way. We approach it with an openness to feelings. A campaign has something it reacts against. An art work does not explicitly have an agenda although it can imply political views.”

In a world where anything can be art, perhaps it is the how and why and what of calling something art that is important. Of understanding what difference it makes. Is this what art school should be about? The development of openness to a state of being that can be world-changing but isn’t instrumentally so? We wanted to save the slide collection, but Adopt a Slide was not just a vehicle for doing so. There was a separate petition for that.

These arguments aren’t exactly new, as last summer’s We Want People Who Can Draw exhibition amply demonstrated. But they seem to have acquired a renewed urgency (the number of recent conferences, symposia, articles and blog posts on the art school subject attests to this — just Google it). Other questions arose from my correspondence with colleagues; important questions that aren’t directly addressed here but are woven throughout. Questions about the relationship between skill and intellect, about material and making and the body and the self. About if and how art education is or should be different to any other discipline. After all, if curiosity, openness and creative thinking are life skills, then surely we need them in every field of endeavour?

Responses to my question ranged from the theoretically complex to the deceptively simple, and it became very clear that what I had thought of as a fairly straightforward question is in fact complicated, conflicted and not likely to be resolved any time soon. Which is a good thing actually, as it opens up possibility. It has generated those experimental alternatives to the formal art school that the afore-mentioned Professor Bauer advocated — in the shape of independent, fee-free, peer-led initiatives such as the Islington Mill Art Academy (Salford), or School of the Damned (East London), although it seems to me these are more of a postgraduate than undergraduate phenomenon.

So it doesn’t let the university art school off the hook. The widespread reduction of British education to a market ethos poses a fundamental threat to the development of creative thinking per se. And this comes in two directions. At an institutional level, it is the continual and pervasive scrutiny of outputs; the breaking down of time into smaller and smaller discrete chunks; administrative structures that allow no room for flexibility. At the other end, it is the way a generation of schoolchildren and students are becoming habituated to the idea that education costs and that the only measure of success is ‘getting it right’. So that what’s in it for them has to be concrete, immediate, and worth the money. Of course students want to come out of higher education with skills and knowledge that will equip them to earn a living. But higher education should not be just about training for a job of work. It ought to be about flexing your wings, possibly for the first time, in a place where you have room to do so. It ought to be about seeing how that feels and where it takes you, about beginning to find out what you’re made of and what matters to you.

All rather nebulous-sounding, maybe, but it is this that makes people creative thinkers and problem solvers. And it’s not free and easy at all, it’s actually remarkably challenging. But this is what art school is really good at, and this is why it is not pointless, but more important than ever. We lose sight of this to the detriment of our whole society.

I don’t know what to do about tuition fees and administrative rigidity and ‘tick-box’ assessment criteria, other than to debate them, critique them, challenge them at every opportunity, as intelligently as possible. Meanwhile, I would urge new and returning students and their tutors — hell, everyone really — to take the advice of Hazel Jones, Senior Lecturer in Interactive Arts at Manchester School of Art. Go out and measure puddles and not know why you’re doing it. Beat a sheet of metal into a dome because it feels good and is really noisy. Pick just one image from 300,000 and wonder why you chose it. Pay attention to your curiosity. It matters.

Liz Mitchell

This article has been commissioned by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network North West (CVAN NW), as part of a regional critical writing development programme funded by Arts Council England — see more here #writecritical

With thanks to friends and colleagues at Manchester School of Art

Images, from top: Feminist art slide, from Manchester School of Art’s historic Visual Resources Centre; We Want People Who Can Draw exhibition; LJMU Fine Art MA visiting The Hepworth art gallery; Computer art slide, from Manchester School of Art’s Visual Resources Centre; Islington Mill, Salford