“Free speech my arse”: We Want People Who Can Draw — Reviewed

‘Nice rebellion, welcome in’: Liz Mitchell visits a provocative and timely exhibition challenging all those who care about the state of art education, now and in the future…

It’s quiet in the Special Collections Gallery at Manchester Metropolitan University on the day I visit. Tucked away on the third floor of the university library at All Saints, you must pass security guards, identity checks and rows of books and computer terminals to get here. All still, now that the summer holidays have begun. But a few short weeks ago, this place was buzzing. End of term exams and the Final Year Degree Show at the Art School just over the road. People unloading curious structures from rented vans, disobeying the no-smoking signs, giggling and fretting and shrieking on the street. Energy levels were off the clock.

A few weeks earlier, students staged a sit-in at the nearby Manchester Business School. A group calling themselves Free Education MCR occupied the Harold Hankins Building in a demonstration against further education cuts, rising tuition fees and the planned transformation of the building into a £50m hotel. A statement on their Facebook page read:

‘We know what the market does to education, and we know we need to fight it. We are occupying to reclaim space from the university’s corporate projects – and to use it to educate ourselves freely.’

This kind of protest is on the rise. Earlier this year, students occupied the London School of Economics, proposing a Free University of London, run by students, lecturers and workers. New independent art schools, such as Open School East in London and Islington Mill Art Academy in Salford, offer a collaborative, socially engaged and fee-free alternative to the perceived neoliberal market ethos of university art education. Similar projects are supported by high profile contemporary artists such as Matthew Darbyshire, Ed Atkins and Ryan Gander, himself a graduate of Manchester School of Art.

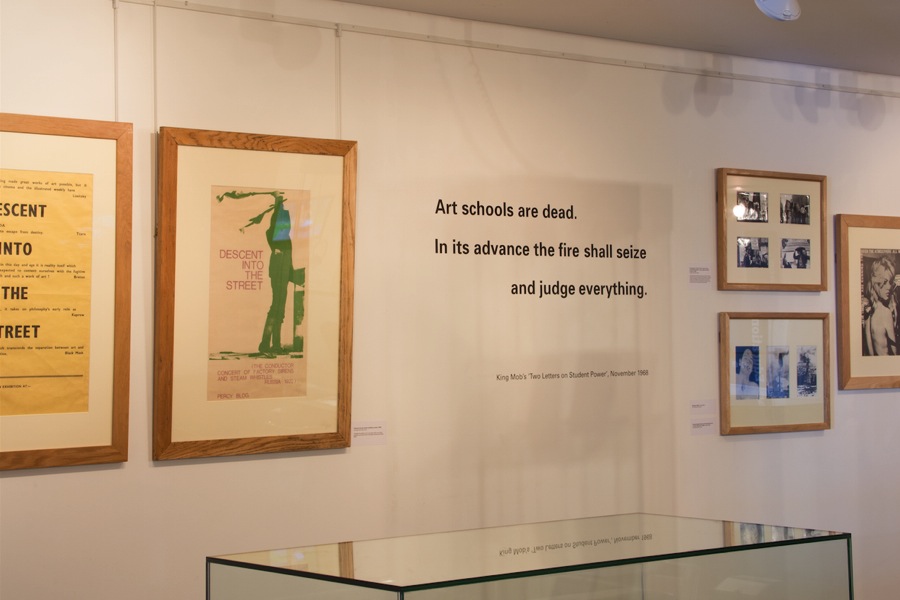

But today, all is quiet. Low level ambient lighting, the background shush of air conditioning. Glass cases containing an array of archive material – pamphlets, posters, photographs and magazines. On first impression, they are rather beautiful; clean typography, bold graphic design, crisp printing. There is also a whiff of archive nostalgia, in the soft black fuzziness of manually typewritten text, the yellowing of cheap paper now crisped with age. But don’t be fooled by the apparently benign atmosphere – this is a Trojan horse. Get a bit closer, read the typewriter’s words. This is a call to arms. A clue lies in the vinyl lettering on a far wall:

‘You may think that the Art College is very free and easy.

But it is not…’

We Want People Who Can Draw looks back at a critical moment in the history of the art school, a moment that feels remarkably relevant in the current climate. The 1960s was a period of significant structural change in British art education. Prompted by the recommendations of the 1960 Coldstream Report, that art schools become more ‘academic’, it coincided with wider cultural and societal shifts – the emergence of Conceptual Art, the mobilisation of anti-capitalist politics, and post-structuralist debates around the very concept of knowledge. From the mid-60s, the art school became a site of protest that directly challenged establishment authority, hierarchical power structures and gender discrimination. The exhibition documents the activities of this period through its communication media. Its content is passionate, outraged, idealistic – up close, its energy threatens to break out of the regulated spaces of display.

It begins politely enough, with a large printed broadside proclaiming ‘first things first’ in heavy black copy, the full height of the page. This is a manifesto, proposed by designers, photographers and students weary of the relentless push of consumer advertising. It calls for a socially engaged design practice that produces instruction manuals, educational aids and road signage, in place of the endless flogging of cat food, toothpaste, ‘roll-ons, pull-ons and slip-ons’. Self-published by Ken Garland in 1964, it was swiftly reproduced across art schools nationwide. A revised version was published in 1999, arguing that the situation had got worse, not better. And this is still a live document – read its current manifestation at firstthingsfirst2014.org.

Further in, the tone is more strident. There is a two-page typewritten statement by university art librarian Ron Hunt. Written for a 1968 art school demonstration in Trafalgar Square, this document is furious. Rogue lines of words zigzag across the page, slicing aggressively into the main text with statements such as: ‘free election of masters does not abolish masters and slaves’; and: ‘FORGET ALL YOU HAVE EVER LEARNED: BEGIN BY DREAMING’. In the main body of the thing, Hunt asks:

‘How many more vice-chancellors and principals are going to make speeches that welcome student rebellion, and give us the old gab about the higher education establishment being built on a tradition of free speech which is still upheld?…Free speech my arse.’

Ouch. I wonder if the newly appointed VC of Manchester Metropolitan University has visited this exhibition yet.

And this is the curious thing. On the one hand this is a serious historic exhibition, drawn from a number of important archives, including Manchester’s own. It documents the notorious art school sit-in at Hornsey College of Art, which resulted in the sacking and expulsion of staff and students. It includes pamphlets and statements from the Slade School and RCA women’s groups of the 1970s, following the revolutionary politics of ‘Second Wave’ feminism. It shows how early 20th century avant-garde art was mobilised for contemporary political ends. A poster advertises Descent into the Street, an exhibition of photographs of avant-garde artworks exhibited in the Physics Department of Newcastle University in 1966. In clean, san-serif font, it locates 1960s activism in a direct lineage from Russian Constructivism through Dada and Surrealism, with quotes from El Lissitzky, Tristan Tzara, Andre Breton and Allan Kaprow. The last is from Black Mask, a New York-based anarchist group:

‘We seek a form of action which transcends the separation between art and politics: it is the act of revolution.’

Black Mask, and similar groups such as the Parisian Situationist International and its British equivalent, King Mob, advocated the active disruption of everyday life. The exhibition’s title is a variation on a pun in a King Mob publication, Echo, in which the statement ‘We’re looking for people who like to draw’ was placed next to an image of a gun. Both Black Mask and King Mob adopted Valerie Solanas as their figurehead, after she shot Andy Warhol and art critic Mario Amaya in 1968.

And to this exhibition, located within the art school right now. Its main audience is the student and staff body. Are its curators (also students and staff) advocating the toppling of the establishment; the taking out of those deemed to have sold out? I don’t think so. But what they are doing, perhaps, is contesting ownership of a history of radicalism. Nowadays, artists are expected to be dangerous and unpredictable, it’s a commonplace of contemporary practice. As Grayson Perry put it in his Reith Lecture: ‘nice rebellion, welcome in’. There is no escaping the market. But, as one of the exhibition’s curators put it, these artefacts reflect moments when students and staff refused to accept the limitations of established experience:

‘The most radical thing they did was ask the questions that according to the given order of the art school were not meant to be their questions.’

Is this what the art school should be for then? To enable the framing of new questions, new possibilities, regardless of whether or not you have permission? To provide time that is not measured, quantified and allocated in market-bound units, but (as another member of staff put it) that enables you to go out and measure puddles and realise it is a valid occupation? Maybe even an important one? These are the kinds of questions We Want People Who Can Draw provokes.

You don’t need to be a member of the Library to visit Special Collections. But you do have to approach the security guards and ask them to let you in. The tension between content and venue in this exhibition is perhaps one of the most interesting things about it. But it would be a shame if this prevented people from seeing what seems to me a most provocative and timely challenge to all those who care about the state of art education, now and in the future.

Liz Mitchell

See We Want People Who Can Draw: Instruction and Dissent in the British Art School at Manchester Metropolitan University, Special Collections Gallery, until Friday 31 July 2015

Gallery open Monday -Friday 10am-4pm

Download the exhibition catalogue free of charge here

All images courtesy of David Penny and Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections, apart from the second image down, which was taken from the Free Education MCR Facebook page

This article has been commissioned by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network North West (CVAN NW), as part of a regional critical writing development programme, supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England — see more here #writecritical