Venice, Liverpool, Porto Alegre, Folkestone… Why Biennial?

As the world’s oldest (and revolutionary) biennale opens its doors again this weekend in Venice, Tania Moore looks at the art festival format as a whole, and asks why we keep coming back for more…

You may have noticed that the artistic community is gearing up towards the 56th Venice Biennale: the curatorial concept has been dissected, artists have been announced, and arts professionals everywhere are packing their bags for the international exhibition, due to open this Saturday.

This biennial, an international stage for art since 1895, was revolutionary. Other biennials didn’t begin to crop up until the 20th century, and the 21st has since seen biennials erupting across cities in almost every country in the world. In 2011, the International Art Newspaper (Biennial or Bust, Ben Luke, June 2011, issue 225) quoted that there are around 300 global biennials (catalogued in depth by the Biennial Foundation).

The biennial — or triennial — as an artistic format is certainly popular, but the question must be raised: why do we need a multitude of biennials, what are their aims, and why do we keep on visiting? In short: why biennial?

Biennial festivals are widely credited for bringing internationally respected art, particularly contemporary art, to areas that wouldn’t otherwise have such access. The 2015 Venice Biennale will house work by Marlene Dumas, Steve McQueen, Bruce Nauman and Chris Ofili, amongst over 100 other artists in the central exhibition alone. Last year’s Folkestone Triennial, by comparison, brought the work of Andy Goldsworthy, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Yoko Ono and Pablo Bronstein to the public spaces of the town. Biennials can offer juxtapositions of established names and emerging artists that wouldn’t be found anywhere else: this alone attests to the influx of visitors they draw.

The motivation to visit a biennial seems clear to justify, but their aims can be more complex.

The last edition of the Venice Biennale in 2013 greeted over 465,000 visitors from all over the world. Folkestone Triennial predicted over 120,000 attendees for 2014. Many cities would not draw such impressive figures without the intervention of a biennial. Despite such statistics apparently proving this format’s popularity, their value is consistently brought into question.

Last year, Liverpool Biennial and Folkestone Triennial attempted to examine their own purpose at the International Biennial Summit and the Sculpture Question respectively. Participatory events such as these demonstrate the success biennials have when they address their own practices and engage with wider audiences, rather than merely importing art without consideration of its impact.

Despite a multitude of biennials, the format denies repetition by creating individual identities that are often implicitly tied to local culture. Successfully utilising the identity of the city can be manifested by appropriating their unique spaces. Folkestone Triennial exclusively commissions artists to create work for the public spaces of the town. Approximately one third of the sculptures become permanent, so new spaces are needed each time. The works in the first two triennials were predominantly located on the seafront, being obvious destinations.

However, as these spaces have been used up, other locations have been selected: thus liminal space becomes destination. This has drawn out lesser-known histories of the town, such as Jyll Bradley’s Green/Light (for M.R.) (2014): a light installation that stands on a previously abandoned gas works. Folkestone Triennial is a particular success story in considering its impact on place, but other biennials have at times failed to achieve this. Liverpool Biennial’s group exhibition in the Old Blind School in 2014 did not exploit the history that permeated the building. Instead, artworks seemed to have been placed randomly with futile connections to each other and their location.

Many biennials are staged simply to position a place as a destination. Despite the proven economic benefits of tourism (see the Economic Impact of the Liverpool Arts Regeneration Consortium (LARC) Final Report, September 2011), speakers at the conferences in both Liverpool and Folkestone problematised the issue of bringing in external visitors, placing them in opposition with a local public. Arts events are often criticised for being inaccessible to local audiences; whether through high entrance fees, using unintelligible art-speak or by failing to address local culture adequately.

Many biennials strive towards addressing their locality through specific activities aimed at local audiences. At the International Biennial Summit, Curator Monica Hoff described the activities of the Mercosul Biennial in Brazil, based in Porto Alegre, which has enlisted over 2,000 mediators to work with the 400,000 students that visit each time: an unquestionably valuable task that directly affects local groups. She described her biennial as a “political organism” rather than an exhibition. A poignant intervention brought about by the fifth Marrakech Biennial in 2014 was a sound installation in taxis, which encouraged discussion between driver and passenger.

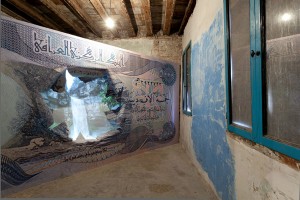

Each biennial that emerges adopts a slightly different approach, therefore overcoming potential repetition. Although the Venice Biennale’s model of national pavilions has been criticised for being outdated, it does prove to be valuable for promoting international art. In 2011, Iraq showcased a pavilion at the Venice Biennale for the first time since 1976, which was criticized for presenting artists living outside of Iraq. Organisers argued that this was due to logistical constraints due to the political situation in the country. The criticism was answered, however, in the pavilion’s next, critically acclaimed exhibition Welcome to Iraq. The presentation directed a spotlight onto a country that had for so long been denied international acknowledgment of its culture.

This is only one example that demonstrates the political situation that many cultures have to overcome to partake in or stage a biennial. The 2013 Istanbul Biennial was reduced and moved out of the planned public spaces and into existing galleries due to protests at the prime minister’s regime. When considering that a biennial’s aim is to reclaim abandoned spaces and bring art to non-art audiences, this was a disappointing development. The biennial can be a fragile model.

The value of the biennial is consistently brought into question because many of its positive effects are unquantifiable. Many funding bodies therefore struggle to justify backing them. Biennials are often denied public money; instead organisers have to look to private funders. Speakers at the International Biennial Summit stated that they are continually answering the question: ‘Is it locally relevant? Is it globally important?’ These questions are difficult to answer, particularly for new institutions.

So: why biennial? As Maria Hlavajova, Director of BAK, states: “The question remains unanswered, if not, unanswerable.” With new biennials continually emerging and each adopting a different format, the question itself is as changeable as the exhibition model. But biennials continue to prove their worth in ever-changing ways, whether through bringing art to new audiences or artistic innovation to established ones. The defined aims of each particular case will impact on the type of art on offer and the criteria for success.

Tania Moore

This article has been specially commissioned for The Double Negative by Liverpool John Moores University and Arts Council England. Part of the collaborative #BeACritic campaign — see more here

Further reading: Dany Louise’s MPhil paper Destination Biennale! An examination of the interface between biennials of art and public policy within a neo-liberal context

The 56th Venice Biennale launches this Saturday 9 May and continues until 22 November 2015

Read all our biennial coverage here

Images from top: Green/Light (for M.R.), Jyll Bradley for the Folkestone Triennial (2014); Sir Peter Blake’s Dazzle Ferry for Liverpool Biennial, 14-18 NOW and Tate Liverpool (photo courtesy Mark McNulty, 2015); Iraq pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2011)