Conflict And Transformation: The International Biennial Association Summit

What do biennials do, how do they do it and why? Pete Goodbody attends a summit of experts and finds that the needs, hopes and expectations placed on our arts festivals are as complex as ever…

Biennial arts festivals are precarious things. They rely on the goodwill of their audiences and, in most cases, the willingness of public bodies to provide funding. But this creates a tension between artists and those who commission or curate art who want to push boundaries and funders on the other who tend to play safe.

This conflict was a recurring theme during the course of the discussions at the International Biennial Association Summit, held at the Bluecoat in Liverpool on Saturday. Here was an opportunity for representatives from Biennials and Triennials around the world to come together and share experiences of what they do, how they do it and why. It is part of an international dialogue where the sharing of ideas on the practice and experience of different arts festivals can help support each other. Thus, we heard presentations from nine Biennials around the world divided into three discrete panels.

The first panel looked at pedagogical models and work in the community. Here it quickly became apparent that it is not enough simply to put on an exhibition and hope people will come and see it. There needs to be a conversation with the audience. Nevenka Sivavec from the Ljubljana Biennial, Slovenia, explained how this Biennial changed from originally being prints only — because they were easy to send — to more public realm and performative work. In the 2011 edition, there were no prints at all, and the more performance-based show tended to lose a lot of the old audience; replaced with a new, younger crowd who responded well to community-based ideas.

In a remarkable parallel with Liverpool Biennial’s Anfield-based Homebaked project (2012), she told how they worked with a local catering school to set up a bakery installed in gallery space to bake “biennial biscuits”.

Monica Hoff talked about the educational experience of the Mercosul Biennial in Brazil (below) and how that branches out to inform artist projects, public programmes, and workshops. There are spectators and collaborators; a workforce that generates knowledge for itself and the city. It is seen as a public service. There are more than 10,000 teachers and 150,000 students involved in activities around their biennial. This model helps to remove the need to explain high art to the audience, because the audience is getting involved in the entire process.

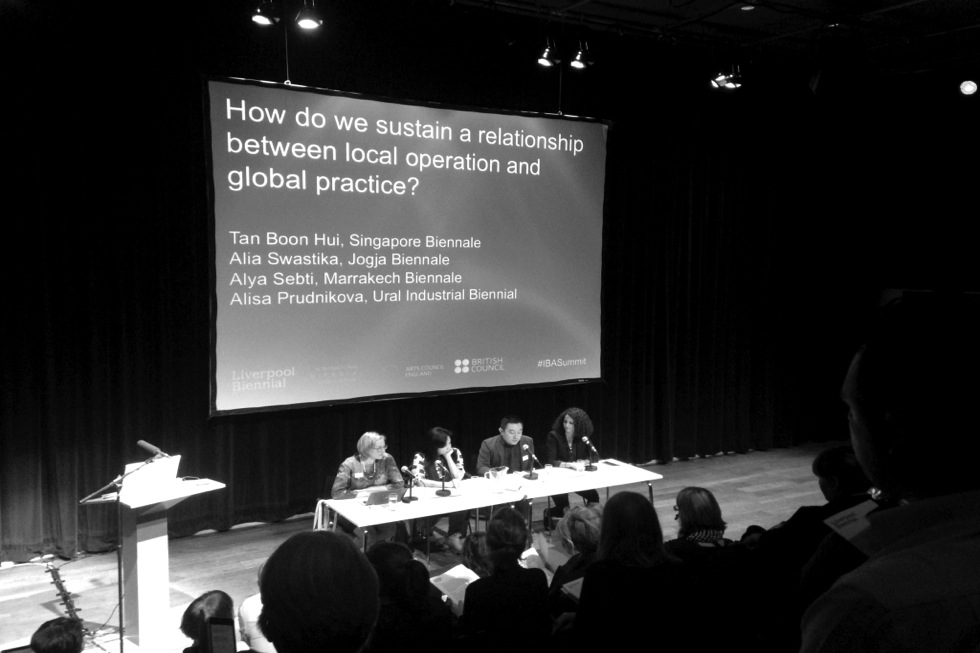

The second panel was described as a discussion about sustaining a relationship between local operation and global practice. However, and inevitably, perhaps, there was a tendency to veer off topic, and this became more about the differing reasons and rationales either for putting on a biennial in the first place, or arriving at the particular model employed today.

Alya Sebti described how the Marrakech Biennial has evolved to engage with the local audience and to make the art on show more accessible. There was a perception in Morocco that only the elite had access to art, and the festival wanted to attempt to reach a non-art audience. Language is an issue in Marrakech. The population speaks French, Spanish, Arabic and Morrocan and many don’t cross over. This biennial experimented with performance in public spaces as a new way of transmission; sound installations in taxis were also used to engage people and create dialogues. That meant a large number of people were aware of the event and could participate in it, more than might otherwise have been the case.

Alisa Prudnikova was candid in her talk about the Ural Industrial Biennial. This was born of the desire to show the world what the area around Ekaterinburg has to offer in terms of industrial opportunity. It was also seen as a research platform into gaining an understanding of how art can influence daily lives. As the region is known for the manufacturing industry, this biennial works closely with local business to use industrial spaces for exhibitions, giving people access to spaces that would otherwise normally be fenced off.

The Jogja Biennial in Indonesia was founded in 1988 and has always been seen as a community initiative, mostly involving local artists. In 2010, there was a discussion about redefining and re-formulating the biennial format, and Alia Swastika explained how they arrived at the idea of the “Biennial Equator”. There is no real arts infrastructure in Indonesia, so an international model was developed where each biennial will now work with a partner country or region. The last two festivals have seen partnerships with India and the Arab region; the next will be with Nigeria (where, Alia told us, apparently Indonesian instant noodles are a big thing). The co-curation with the partner not only provides a mix of Indonesian and partner artists, but it creates a valuable connection between countries.

The three different models in this panel all had a common thread: the rationale for a biennial must show a benefit for the community. That’s what funders expect. Whether it be tourism, cultural involvement or education, there must be a tangible, quantifiable benefit to be derived from this type of arts festival. Else why do it? The Indonesian Biennial is young in its current form, but already the Indonesian government sees the benefits on offer from the partnership format and is prepared to provide funding.

The third panel looked at a model for future biennials. Here it was recognised that biennials are complex beasts and although it is helpful to study others, there is no single form or format a biennal should take. Thus, even before we start, it is impossible to describe a single model for the future. Biennials are all different as a response to their own space, region and purpose; the model for the future is also shaped by funding requirements and the need to reach out to an audience.

Navigating these parameters was described as being somewhere between compromise and manipulation. Here again, the speakers were nodding towards the tension identified at the start.

To an outsider (me), this summit offered an important insight into the struggles that go into the production of a biennial. For the delegates, I would think they all recognised something familiar in each of the talks, even though there were many different models and perspectives presented. Biennials may well be precarious, but to give the last word to Marieke van Hal (the Chair of the Biennial Foundation), “their ability to morph into something different every two years can also be seen as a strength.”

Pete Goodbody