The Art Of Gothic

During the mid-18th century, Gothic Horror surged into mainstream culture, with literature, film, art and poetry all exploring this darkest of genres. As Gothic programming returns full force — invading the BFI, BBC and British Library — Heather Garner looks at our enduring fascination with all things curse-ridden…

“There is no bombast, no similes, flowers, digressions, or unnecessary descriptions. Everything tends directly to the catastrophe.” – Horance Walpole, The Castle of Otranto

The word Gothic has carried much historical weight with it throughout the centuries. Originating as a derogatory term for the perceived barbarous and primitive artworks of the medieval era, today this genus means much more than the pointed arches, trefoils and intricate filigree that adorns the ecclesiastical architecture of the same name. During the mid-18th century, and out of the age of Enlightenment, Gothic Horror surged into mainstream culture, with literature, film, art and poetry all being used as the exploratory mediums of this darkest of genres. Even children’s stories could not escape the grasp of the Gothic, with cautious tales – the Brothers Grimm come to mind within this period– of mythical creatures and sinister curses being used to establish moral teachings and present warnings to the otherwise innocent young.

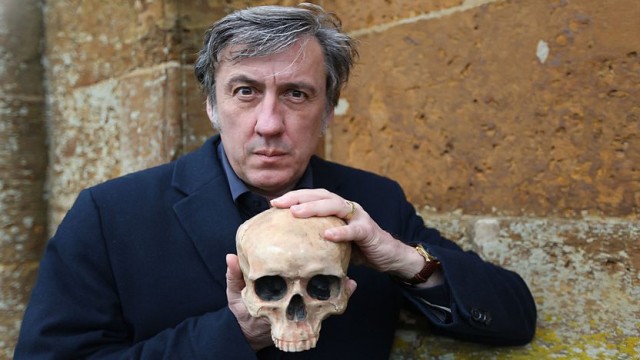

It is this enduring infatuation with all things curse-ridden that has perhaps inspired the recent flurry of Gothic explorations: mainly BFI’s Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film season, the British Library’s exhibition of Gothic literature, Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination, and the recent BBC Four series, The Art of Gothic: Britain’s Midnight Hour.

The beginning of this lasting fixation can be traced to Horace Walpole’s creation of The Castle of Otranto (1764), thankfully featured in the British Library’s collection. It is the tale of Lord Manfred whose son is killed by a falling helmet: an omen he is foretold that will signal the demise of his family. The terror of such a prophecy drives Manfred to madness and from this he emerges a killer. With this novel, the founding father of Gothic literature sewed the sinister seeds for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1823) and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897).

What strikes me about Gothic Horror is its desire to explore human nature in its most extreme and supernatural form: the struggle between light and dark, good and evil. The eternal attraction to and fear of things that go bump in the night; the desire to get the adrenaline rush of a potentially perilous situation, but with the comforting knowledge that we are safe from harm’s way. Gothic Horror blossomed with the invention of moving image, and subsequently some of the most iconic and blood-curdling visual imagery of the 20th century was produced — happily many of which are featured in BFI’s Gothic film season.

The first iconic Dracula film, Nosferatu (1922), was a standard bearer for Gothic Horror. The hunched and clawed shadow of Count Orlok creeping up a staircase is an image that has become indelibly etched on the minds of all who have seen it: a testament to the cinematic magic of director F. W Murnau. Hammer Horror’s version in 1958 returned to Stoker’s vision, as the charismatic Dracula (Christopher Lee) is pursued by Van Helsing (Peter Cushing). At its core, this is a story about the moral struggles that occur within a single individual; as Walpole puts it in The Castle of Otranto, “We are all reptiles, miserable, sinful creatures. It is piety alone that can distinguish us from the dust”.

This struggle between good and evil is sadly not something that remained fixed to the printed page or the cinema screen. The rise of mechanised warfare during the 20th century brought about true horrors that could not be forgotten with the closing of a book. Two world wars in the course of one century devastated Europe and tore rose-tinted glasses away from the entire population: the word horror is a feeble description of the effects of these wars and of the suffering and hellish conditions endured by soldiers, prisoners and civilians alike.

Its cultural ramifications are equally as interesting. Francis Bacon, one of the most prolific and challenging artists of the last century, solidified this loss of innocence and dealt a defiantly incisive blow to the apparent piety that human beings possessed; making clear that we are never too far from the horror of the Gothic nightmare. This notion is disturbingly depicted in one of Bacon’s most famous triptychs, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944). We are confronted with contorted and disfigured bodies that seem to howl and screech in agony and grief. Barely recognisable as human beings, instead they resemble Frankenstein’s monster; a manifestation of man’s pride, and a reflection of the darker recesses of the human mind.

Whether it comes in the form of literature, film or art, Gothic has firmly rooted itself in the psyche of modern culture and, for this reason, rightfully deserves the admiration and focus it is currently receiving through the British Library, BBC Four and the BFI, showcasing the best the genre has to offer. But more than this, it provides us with the spectre of the supernatural, the search into the human consciousness and the simple adrenaline rush and shiver down the spine that is so intrinsically woven into this darkest of genres.

Heather Garner

Watch all episodes of The Art of Gothic: Britain’s Midnight Hour on BBC iPlayer now

BFI’s Gothic: The Dark Heart of Film season includes the longest BFI Southbank season yet (until December 2014), UK wide theatrical and DVD releases, an education programme, a new BFI Gothic book and a range of exciting partnerships — see site for more info!

See Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination at the British Library until 20 January 2015 — £10, under 18s go free