Rachel Goodyear: Liminal Truths From An Artist And Patient

What does illness look like when it becomes an artistic encounter? Alice Hughes explores the difficulty of interpreting illness through art and where empathy and interpretation collide…

Upon first impression, it is tempting to read Rachel Goodyear’s collection of drawings — Unable To Stop Because They Were Too Close To The Line — as tangible autobiography. This work was commissioned by award-winning arts charity LIME in 2006, an organisation part of the Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and is permanently on exhibition at Fairfield Hospital, Greater Manchester. The collection of 31 drawings in white frames occupy a section of corridor directly off the main hospital street leading to medical records; this was chosen so as to be publicly accessible, but allowing visitors to make a choice of whether to view the work or not.

What changes the context of this work is the circumstances under which it was made. In 2006, Goodyear — who lives and works in Salford, was shortlisted for the Northern Art Prize in 2009, and has exhibited her work across the globe — was undergoing a six-month period of chemotherapy for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. This series of drawings is a visual interpretation of her experiences as both patient and artist; a hybrid world of delicately drawn humans and animals, veiled identities, and traces of infertile woodland, colliding with her diary entries, becoming all the time more immersed within these fictions of her making.

Goodyear has expressed the dual nature of her project. “This was an unusual project in that as a patient I was experiencing the illness and treatment, and as an artist I was standing outside of myself and observing what was happening.” Likewise, writer Margaret Atwood has said that art and writing “splits the self into two… he or she is two: one that does the living and consequently the dying, the other that does the writing [or art] and becomes a name, divorced from the body but attached to the body of work” (Negotiating With The Dead: A Writer On Writing, p28).

At this dual point of power and powerlessness, what all artists have to deal with is socio-political and sometimes biographical answerability. There are questions which instead become forced interpretations. ‘Do you paint vulnerable women to remind us that feminist politics is still necessary?’; ‘Is this image a reflection upon your own childhood trauma?’; ‘Are you working to express the re-emergence of racial oppression?’ Such questions are direct responses to the work, yet they become entrapping acts of repetition; boxing humans into pre-set categories and motivations. Expression should not have to abide by expectations, because it is an attempt to create an experimental space, separate from those which already determine our lives. Art works are patchwork fragments of imagination and inspiration, rather than identities made visible. We attempt to make these fragments whole through reasoning, but art is only made entire through sharing.

So perhaps Goodyear’s drawings express at once the realm of an artist and person; but they also articulate the doubled freedoms of an artistic encounter. The artist must let go of their perception of the world and let the audience make their own interpretation; the audience interprets the artist’s perception and experience of the world, but at the same time is liberated by the knowledge that they are not divorced from others in an individualist dimension. If we view an artistic encounter through the lens of film — as critic Serge Daney would call a “face looking at us” — there surfaces the face-to-face mirroring of a close-up on screen. We cannot help but feel the artist’s views and interpretations of the world looking back at us, and learn to accept them as equal to our own.

Subjectivity in this moment is shared; both parties are released from ‘self’ or ‘other’ perception, detachment and judgement. An encounter in Fairfield Hospital with Goodyear’s work becomes a sharing of half-revealed feelings, and so an embrace of the liminal nature of identity. As Rachel Goodyear has commented herself, this collection “is a frozen moment — it is maybe at that exact point when the trees were felled and the characters have all been caught in the act. It reflects that moment when things become clearer, the end of something and starting anew, and the borders of one way of life and another.”

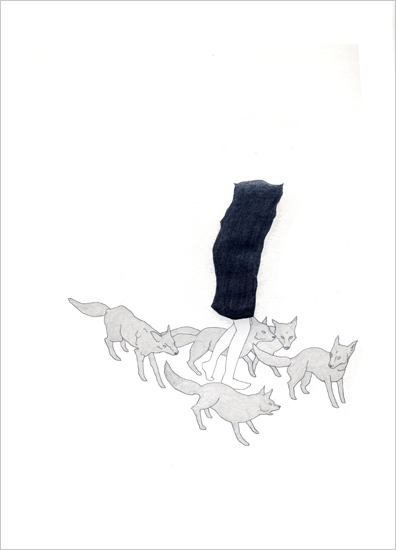

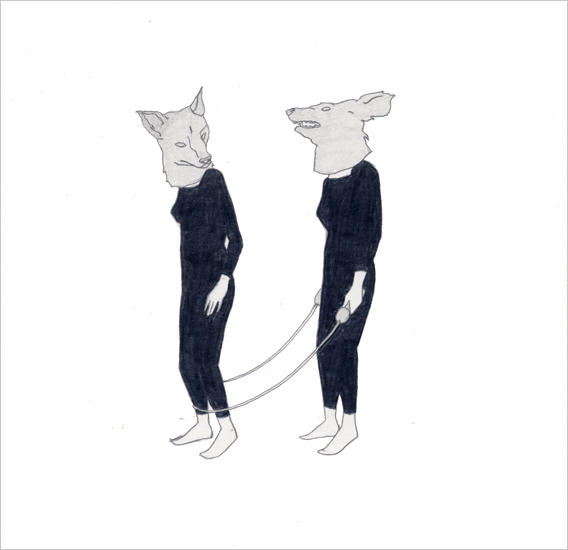

As a collection, Goodyear’s handcrafted snapshots refuse to adopt the oppositional reversal of predator and its prey, of subject and object. There is a narrative of polymorphous possibilities; a character’s struggle becomes a platform for a parallel character’s discomfort. Each operates in dialogue with the rest, and the aching plot becomes shared. To share an emotion is to not only to be sympathetic, but to emphatically put yourself into another person’s position. The drawings are pencil on paper, furthering this tender, direct connection to both Goodyear’s imagination and body. There is little variation in tone: the background is startlingly white, the skin of the girls is formed through unfilled outlines, whilst animals and masks are grey and a few details, such as hair and clothing, are coloured black. This two-dimensionality strengthens the bond between the trapped characters; whether the girl engulfed by a wolf, the dying tree or the weasel trapped between bare human legs.

The drawings are not mere re-appropriations from history, but reflections upon how everyday humanity is not quite definable. What is refreshing about Unable To Stop Because They Were Too Close To The Line is the way in which the white space force focus upon the characters’ positions. It is no longer about cause and effect. Looking at each piece, you do not ask why butterflies have blinded the fawn by landing on her eyes, or what has caused the trees to lose their foliage. You simply help share their burden of unsettlement and confusion.

The archaic tropes may appear to be there: woods, half-clothed girls and beasts. Yet unlike other fairytale subversions which engage in the repetitive reversal, opposition or blank exchange of categories (whether male/female, black/white or good/evil), Goodyear’s characters express shared emotions common to humanity. There is a distinct feeling of violence, disorder, sexuality, deceit, greediness, submission and façade; but there is also no definite code regarding who or what controls each force due to the continual overlapping and blurring of boundaries at work. Together with the characters, who are often being led out of their scene into a new potentiality — like the blinded girl smothered by a black bag, putting her trust in a pack of wolves — we too are illuminated against the misleading rhythms of power and realise our ability to share these feelings.

In the process of releasing Goodyear from her answerability as both an artist and a patient, these drawings free us all from the trappings of cause and effect. They are emotions crafted from the natural mediums of pencil and paper: personal, yet unselfish in the doubled freedom of our encounter. The title of the series itself was selected by Goodyear from an anonymous article, and has adopted a new communal meaning which allows us to enter a space prior to social subjectivity and knowledge. There comes the realisation that there is no subject prior to its entrance into language and social construction. In such a liminally charged, revelatory space, genuine human compassion and identification becomes possible.

You cannot judge an individual’s reaction to an illness, because we are all different. As Good year herself recalls: “The first piece of advice I received from the chemotherapy nurse was ‘don’t listen to the stories in the waiting room’. Illness and treatment are very personal experiences and each person responds in their own unique way.” Public hospitals and accessible public places not considered upholders of classical standards of artistic value are equally vital equalising spaces, because they open new dimensions for value. They are not galleries or museums. When work is chosen carefully to mean something and remain permanent in such surroundings, what Daney calls the “face looking at us” of contemporary art becomes multiple; Self/Other subjectivity is collapsed, beginning a cultural community of equal I’s entitled to diverse emotions, opinions and beliefs. In no way does this call for art to be divorced from its history, but for a movement away from value based upon the artist as celebrity.

Like artists, we all lose control of the spaces we create. But this does not mean that art and the way we view it must descend into an endless play of identity games. Organisations like LIME reassure us that sharing is the closest thing to artistic perfection, because at this moment repetition ends and change begins.

Alice Hughes is part of the #BeACritic campaign — see more here

Twitter: @Rachel_Goodyear

Rachel Goodyear’s commission was and is part of an ongoing programme of arts activity within Pennine Acute Hospitals Trust across all sites, coordinated by Lime. This is a wide ranging programme incorporating artist residencies, artwork linked to environment improvements, performance and photography. The emphasis is on developing artwork and creative projects linked to the Trust’s activity, and integrated into its processes. There is a huge range of artwork across the five sites. More info here

All images courtesy Rachel Goodyear, from the collection Unable To Stop Because They Were Too Close To The Line