Bloomberg New Contemporaries: Disappointment, Sex & Politics

What do you expect from the next generation of artists? Just don’t look for youthful optimism, says Josie Sommer, as she explores this latest batch of New Contemporaries…

This is it: Bloomberg New Contemporaries (BNC) 2014, a 55-artist-strong showcase of the cream of the emerging crop from UK art schools. Showcased at Liverpool’s World Museum, these artists have been selected by a panel of former New Contemporaries, Marvin Gaye Chetwynd, Enrico David and Goshka Macuga.

So, what are we expecting from the 2014 selection?

Video art? Check.

Politics? Check.

An impression of youth? Not quite.

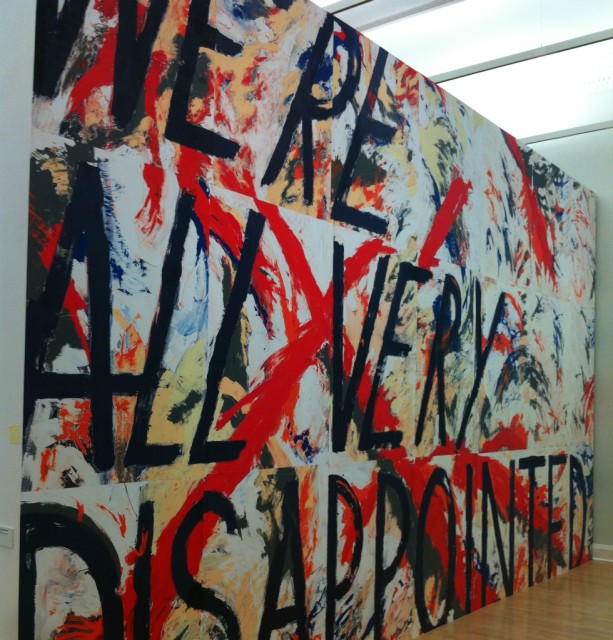

Curated by BNC director Kirsty Ogg, the exhibition starts with an impressive bang: Alice Hartley’s staggering We’re All Very Disappointed (2013). This eponymous 7.8 meter-high banner is defiant yet sombre. Dark red and blue brushstrokes emanate energy, but closer inspection reveals the deceptive control of screen-printing. Registering this subdued facet of angst, sound from Marco Godoy’s video-work Claiming the Echo (2012) floods the space; its dimly-lit choir creating a prophetic, nigh-on apocalyptic atmosphere as a backdrop.

Facing all this is Just Let Go (2012) by Simon Senn, another piece of video art which follows a theme of collective unrest. Senn’s candidly filmed scenario is described as a ‘cathartic’ experience in response to the global financial crisis, as people ‘let go’ — a shirtless rent-a-crowd running around throwing paint, recorded in the style of news footage. Investigating the individual and group dynamics in contexts created by the artist, this work presents faux-violence against conditions that are side-products of the powers that be.

Suddenly, disappointment and collective experience are thrust forward as things to dread. Positive start then. At least it’s lightened by Henry Hussey’s delicately rendered and Marxism-saturated tapestry The Guardian (2013), hung behind Godoy’s choir.

After the initial entry space, the gallery becomes a hash of temporary white walls, with those that are permanent bearing TV screens (specifically for video art) on plinths. Staring down at one side of the gallery, this layout seems almost office-like, as a bank of identical televisions is set against floor-to-ceiling vertical blinds. It is here that the art takes a turn towards sex and relationships — but the majority of it is invested with a gravity or cynicism that one could say lacks ‘heart’.

Nipples formed by animated concentric circles, bouncing and flesh-coloured, are accompanied by a mash-up of orgasmic sounds and beats in Tajinder Dhami’s Electric Dream: Will Synthetic Intelligences Dream of Electric Sheep? (2014). Positioned next to Racheal Crowther’s How 2 Dress (2013), this area seems to take a comical stance on the sexual, as together both pieces create a kind of naughty-noughties vision of sexy: computerised, pink and fake.

Crowther’s photograph of a cropped reclining man, topless and tattooed with “DREAMS” across his stomach, is printed onto habotei silk, permanently fluttering by force of an electric fan. Hovering above this spectacle is a bunch of plastic grapes, dipped in a thick pink substance: too good to be true, faceless, bottomless, and falsely moving, this installation is a tempting lie.

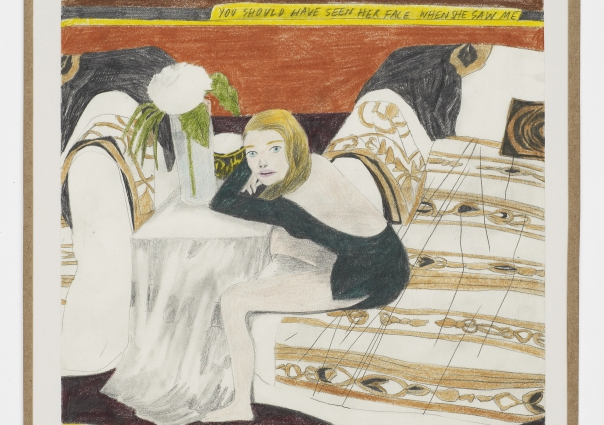

Next up: Be Young, Be Wild, Be Desperate (2013, below) by printmaker Marie Jacotey-Voyatzis is a personal and comic storyboard-esque look at different female sexual encounters and fashions. Mixing image and text, and with a manufactured naïve innocence, this work casts an almost jaded eye upon youthful escapades. All too knowing and witty, Jacotey-Voyatzis’s bank of images plays at coming-of-age when this moment has evidently already passed; a maturity not unfamiliar to the whole exhibition.

Rounding the corner we have Katie Hayward’s Pillars (2013). These amorphous, towering legs jitter with constant fan-powered inflation, and appear like a pared-down version of Niki de Saint Phalle’s work; pale, temporal and colourless compared to the latter’s assertive vibrancy. Hayward’s work explicitly highlights the fragmented body that runs as a motif throughout many of the artworks on show here, as limbs are severed, faces are hidden and features are separated into individual entities across a variety of media.

Destined to be a hit is Reynard the Fox (2013), also known as Matt Copson. The crude, angular outline of a fox, painted in thick, black strokes on a white wall is lit up in alternating colours by a projector, while ‘Reynard’ bites his way through a hateful monologue on adjacent speakers. Discriminating against everyone (“I hate… medium-build white Caucasian males, babies…”), Reynard’s outburst turns to remorse, and it’s hard not to draw parallels between this angry fox and Herman Hesse’s ‘wolf of the steppes’ – a provocative mixture of magic realism, illusion, and the individual struggling in society.

At the last corner, the show becomes more muted, perhaps due to a compilation/impact-tracks-first style of curation, as well as a more earthy hue. Two paintings by Melissa Kime add narrative weight to politics through illustrative aesthetics. Technicolor Joseph and the Amazing City Bankers (2013) depicts grey bankers, one kneeling, one two-faced and holding a satchel apparently blood-stained. With bird-like planes (or are they drones?) jetting overhead, this intricate painting knows more than its style promotes.

There are punctuations throughout this year’s New Contemporaries exhibition that don’t necessarily correspond to the themes of the neighbouring artwork, and these pieces seem to be those which indulge in a welcome fascination with form. Sculptural works such as Ian Tricker’s texturally-polarised and futuristic, motion-suggesting Flux (2014, main image) and the delicate, site-specific Castle (2014) by Jonathan Meira, heighten awareness of the physical and the way bodies interact with an artwork and space, demonstrating a thoughtful consideration of the mixture of forms and mediums in the selection process this year.

Threading back through the space and thinking about the work collectively, there is a notable absence of what you might expect of ‘youthful’ artists: excitement, hope, or maybe a sense of looking to the future. The pieces on show are sophisticated and knowing; together they emanate a seriousness which verges on malaise, and helps these New Contemporaries sit comfortably in the conventional Victorian museum space of the World Museum, a position that seemed initially paradoxical.

Echoing with sophistication mature themes of disappointment, false sexuality, relationships and politics, this year’s selection of New Contemporaries have all too knowingly already come-of-age.

Josie Sommer

This review was the result of a public #BeACritic afternoon for aspiring critics, hosted by The Double Negative, at the press view of Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2014 — more here

Read more on the #BeACritic campaign here

Bloomberg New Contemporaries continues at the World Museum, Liverpool until Sunday 26 October 2014. It then travels to the ICA, London from 26 November 2014 until 25 January 2015