Richard Hawkins: Hijikata Twist

Tate Liverpool’s Exhibitions and Displays Curator Darren Pih explains the ‘dirty avant-garde’ thinking behind Richard Hawkins’ new show…

Since emerging in the early 1990s, Richard Hawkins has evolved an emphatically diverse practice that defies easy categorisation. Working in a range of artistic disciplines, including writing, it is collage that constitutes his primary artistic medium. Its capacity to bring together dissimilar and contradictory visual elements and ideas provides the philosophical device and method by which he expresses his vision, while reflecting the depth and eclecticism of his knowledge.

Weaving together alternative, neglected and often incongruent narratives, Hawkins speculates on the connections and overlaps across a diversity of subjects, including decadent French sub-cultural literature, ancient statuary, low-brow horror, art history and the teenage heartthrobs of 1980s pop culture. Despite the diverse nature and appearance of his work, a profound conceptual rigour underpins his vision: it focuses on the thrill of the intense gaze and the relationship between this and the creation of meaning.

Exploring the ways in which beauty and rapture can coexist with ugliness and imperfection, or how visual intelligence and complexity can coexist with what is supposedly ‘mindless’ or ephemeral, his generosity of approach proposes an expansion in the sources that inform critical thinking and understanding, forcing a reappraisal of our assumptions about the nature of artistic process and influence.

The exhibition brings together recent and newly created works by Hawkins to explore the ways in which classic western figurative painting can be interpreted or ‘twisted’ to create ideas far beyond those usually associated with art history. It presents mid-century works from the Tate collection by Francis Bacon, Hans Bellmer, Jean Dubuffet, Willem de Kooning and Graham Sutherland, chosen by Hawkins to reveal their unlikely effect on the work of the Japanese artist Tatsumi Hijikata, a seminal figure and inspiration for radical and experimental culture in Japan over the second half of the 20th-century.

In particular, Hawkins is interested in the overlooked effect of western art on Hijikata’s founding of ‘Ankoku Butoh’, a performance art and dance movement referring to forms of traditional Japanese dance (‘butoh’) and ‘ankoku’, which alludes to extreme ideas of abjection, darkness and eroticism. This led to butoh being referred to in Japan as the ‘dirty avant-garde’, echoing Hijikata’s statement: “The dirty is the beautiful and the beautiful is the dirty, and I cycle between them forever.” Hawkins’s collages explore the influence of western art on butoh, speculating on further connections across various art-forms and disciplines, while at the same time revealing the influence of Hijikata on his own work.

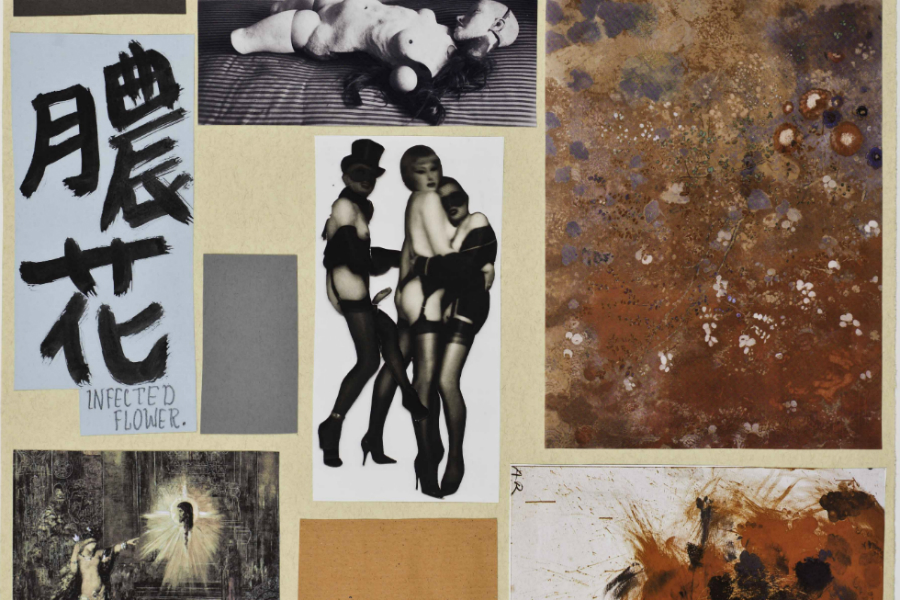

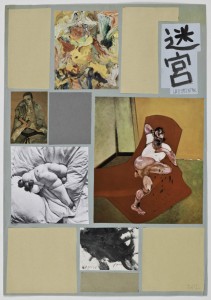

Traditional accounts of butoh tend to regard it as an expression of Japan’s existential trauma and militarised reconstruction in the aftermath of the Second World War. Complicating such partial readings, Hawkins became fascinated by the tangled influence of western art by studying Hijikata’s ‘butoh-fu’ – the scrapbooks he used during the 1960s when devising the art-form (selected scrapbooks are presented within the exhibition). When producing the scrapbooks, he would look through Japanese art magazines, choosing and cutting out the pictures of western art which he liked. He would then sticky-tape the cut images into the pages, rearranging them in a quasi-artful manner, adding scribbled handwritten interpretations, described by Hawkins as “an intriguing form of recorded inspiration, a disentangling of figurative abstraction in visual art with a tendency towards the erotic, if not the all-out obscene.”

The nature of Hijikata’s interpretations, however, inspired Hawkins to channel the choreographer’s voice as a poetic guide towards the creation of further works, some informed by Hijikata’s literary sources and others fabricated by Hawkins, opening up additional speculative connections between different art forms.

Hijikata’s annotated interpretations often focus on the extremes of the human body and behaviour. Delighting in their perverse extremity, he typically describes scenes that veer towards the depraved or the fantastical and the exotic; the female figure in a de Kooning abstract expressionist painting is identified by Hijikata as an “old prostitute” with a face and body distorted by icy winds, while Vincent van Gogh portrayed in Francis Bacon’s painting is described as having “a body composed entirely of particles [...] His skull packed with branches and straw”. Such readings reflect a profound interest in the work of decadent French writers such as Marquis de Sade and Jean Genet (a shared intellectual touchstone for Hawkins), as well as the surrealists Antonin Artaud and Comte de Lautréamont, who aimed to create new meanings through shock montage and the intermingling of wildly incompatible images.

The exhibition explores the transfer of influence, for instance, between the motifs of gesture and painterliness in Dubuffet’s figurative canvas The Tree of Fluids (1950) – identified by Hijikata as “a monster made from dust” – and the “corrupt” surface and unseemly bodily performance of butoh. Hawkins’s works oscillate between ideas of revulsion and attraction; his belief in the human mind’s capacity to occupy multiple contradictory positions reflected in his use of cut and pasted imagery.

The gridded composition of Hawkins’ juxtapositions further refers to the making sense of disparate information. In this way, his work points towards a redefinition of collage as the construction of meaning, rather than a mere arrangement of forms.

Bringing together mid-century western works alongside interpretative notes from a Japanese artist, translated into English with new works by Hawkins, the exhibition traces unexpected relationships and meanings between different art-forms and disciplines on different continents.

The exhibition exemplifies Hawkins’s expansive artistic practice, enabling us to regard Hijikata’s exoticised reading of western art in his creation of butoh as a form of Orientalism in reverse. It also demonstrates how we might consider the blind spots and omissions in history, as well as the supposedly unapproachable or taboo ideas, so they might be embraced and integrated within an expanded visual and cultural realm, and within political and historical narratives.

Darren Pih

Richard Hawkins: Hijikata Twist continues until 11 May 2014 (free entry)

This essay is taken from Tate Liverpool’s new seasonal publication Compass. Available for £1, exclusively at Tate Liverpool, it features articles exploring the exhibitions on each floor of the gallery. Find out more information about Compass here

Images: Main: Ankoku 12 (Index Infected Flower) 2012 (detail), Collage, © Richard Hawkins. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

Centre: Ankoku 10 (Index Labyrinth) 2012, Collage, © Richard Hawkins. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York