Why Be A Critic?

C James Fagan on why anyone would want to be an art critic, and perhaps more importantly, why criticism is needed at all…

What is the point of criticism?

Why be an Art Critic?

Maybe it’s time to address the role of the critic, considering their position within a world which asks for an instant hashtagged response. From Twitter to comment sections, to the numerous amount of blog posts (43 million per month by WordPress stats), everyone is free to say something; whether it’s a brief ‘ACES!’, a considered response to a world event, or a good-old-fashioned sweary rant.

There’s a surplus of views out there, and this has inevitably led to a strange paradox of many publications relying on this surplus to fill their own websites and blogs.

After a while of writing, unpaid, for a known publisher, you might get the chance to be paid a small amount for your view.

It seems an apt time to address the role of the contemporary critic.

A lot of what a critic does can seem pretty obvious; a description of the role comes from a derivation of the Greek word kritikos, meaning judgement and discernment.

How do I do that? What are the factors that control and form my judgement? There was a time when a critic was mainly concerned with aesthetics, the beauty of art; yet this is no longer a main objective. So what, as a post-conceptual critic, am I judging?

Well, if you take a critique or review as a form of communication, then as a critic I’m judging a particular artwork’s effectiveness to communicate the artist’s intentions, and its ability to express meaning to the viewer. Artworks don’t exist within a vacuum, however; we as critics are equally making judgements regarding the gallery curator’s ability to convey their concepts through that particular selection of work. We are also comparing and placing these works into the context of art history, and even popular culture.

In my own reviews, I have also included the journey to the gallery space and even the weather. To include these may seem trivial but these are the elements that can disrupt an art critic’s – indeed anybody’s – perception. This may be hard for some people to believe, but… critics are human. They have many factors playing on their minds and judgement, and therefore must be honest with their readership. Ultimately, we are using our personal knowledge, history and experience to interpret and formulate an opinion on whatever artwork or exhibition we have chosen to see.

Art critics use these factors to make judgements on the merit and success of art, artists and institutions. Sounds like a rather grand statement, doesn’t it? Yet within this relativistic world it contains the difficult idea of proclaiming judgement on others. It also conjures the image of a Clement Greenburg-esque critic, forming a formal consensus on what is to be termed art and judging art solely on their visual aspects or the use of specific mediums. This is what the conceptualists reacted against: creating work that fitted into a wider social context that came with an element of self-criticism.

So, why be an art critic? I rather romantically (get ready for another grand statement) see the role of the critic to be creating a dialogue between artists, galleries and viewers. To give this trinity my own views and opinions. This is not to say my opinions are the only ones that count. Maybe we should look on art criticism in a manner similar to scientific papers, as things to be examined and questioned. The reason that we do put our opinions out there, why as critics we write things that are critical, is an attempt to address any perceived failings, and to act as an independent observer, highlighting the success in the art or art organisations.

I have no way of knowing how the readership will react to an article, or whether the artists and galleries will benefit from the waffle I put out. The only indication I have is an article’s passage through social media; and even then, a critical article may not be retweeted or shared widely. Is this a bad thing? Perhaps. At the very least, when a gallery shares a negative review about one of its own shows, then that gallery is proving it has the confidence in its exhibition and is willing to engage in critical debate. Galleries and critics do have a symbiotic relationship; without them I’d have very little to write about. As critics, we can provide a supplement to the curation. We can offer a way into an exhibition or even a sense of what it was like to experience it for people who can’t be there. Though we must be mindful not just to be an extension of a gallery’s publicity material.

You can argue that I am sharing my opinions too late, coming as they do after the last wall has been painted and long after the last mark has been made. Maybe, but we also have to address the fact that art isn’t contained within the gallery walls; it is a malleable thing open to interpretation and changes in perception.

After eight hundred plus words, am I any closer to answering the question of: ‘Why be a critic?’ Well, I hate to say it, but there is one obvious answer: because we like it. Many art critics are people who are engaged and interested in the arts, and often they are practicing artists themselves. Any critic must consider that when they write an article, they are entering into a process that will, hopefully, make a contribution to the wider art world.

After all, artists, galleries, critics and viewers are all engaged in a collaborative process; one that aims to contribute something towards the continuum of understanding of art and its relevance to the world.

C James Fagan

This article has been specially commissioned for The Double Negative by Liverpool John Moores University and Arts Council England. Part of the collaborative #BeACritic campaign — see more here

Main image: courtesy Kresge Art Museum. Donations in the 1960s were facilitated by MSU Art Department faculty member Charles Pollock (brother of Jackson Pollock), and his friend, art critic Clement Greenberg, expanding the holdings of modern abstract painting.

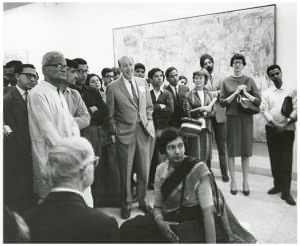

Centre Image: courtesy MoMA. Clement Greenberg speaking in New Delhi in 1967 at a presentation of the MoMA exhibition Two Decades of American Painting.Â