Visibilities: Shaping A Story of Now

Caught up in the rush to diversify, art collections and the narratives they reflect, or don’t, seem more to the fore than ever. Mike Pinnington on an exhibition of Salford University’s Collection that seeks to redress the balance…

It’s getting on for a quarter of a century since the Guerrilla Girls so smartly and urgently pointed out that, when we step into a museum or gallery setting, we’re seeing less than half the picture. Much less, in fact, for it was a picture without the vision of women artists and artists of colour. The point here is twofold: not only that myriad artists have been denied countless opportunities, but audiences too have been deprived of the visions of so many outside a select, relatively small group of, overwhelmingly, white men.

In the intervening years, let’s be honest – despite placatory noises – there has been all too little in the way of meaningful change. That is, until very recently; most notably in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement, which saw BLM top ArtReview’s Power 100 list in 2020. Of its decision, ArtReview said that, among other things, its influence had precipitated a long overdue “rush by galleries to diversify.”

And there has been a spate of programming that reflects the impact, resulting in an upsurge in the diversity of faces and voices seen and heard in galleries. This has come in the form of temporary exhibitions, talks and symposia. But a deeper, longer-term impact, has been felt in the way institutions think and talk about their collections (in terms of both acquisition and display). Indeed, collections and the narratives they reflect – or don’t – seem more to the fore than I can remember. Curators scour gallery holdings with a view to beginning much-needed conversations about where we go from here, and how art can aid in amending the many wrongs committed in skewing the canon.

Take Tate, for example. The jewel in the crown of the UK’s visual arts establishment completely reevaluated their major collection display at its Tate Britain site earlier this year with this in mind. In a press release, director Alex Farquharson said that it “now tells a more expansive story of British art in ways that resonate with us today. We want to show that art isn’t made in a vacuum – It’s made by real people living in the real world. By exploring the connections between artists and the times they live in, we can shed new light on Britain’s greatest artworks and showcase a wider range of perspectives and ideas.”

That wider range of perspectives and ideas is welcome, of course, but an aspect of the story that frequently remains overlooked is one of place, and its impact – on both people and perceptions. Outside of an artist like L. S. Lowry, for instance, it’s rare to see representations of northern working-class life. Unsurprisingly, then, it is away from the bright lights of London and national institutions such as Tate that some vital work is being done. This has meant many a regional space looking afresh at what a collection can and should say and do. Whose stories are they telling, and to what end? Always good questions to ask ourselves when we set foot in a gallery or museum.

Such questions have been to the fore in Salford University’s Collection team for the better part of a decade. Established in the late 1960s (coinciding with the founding of the University itself), it is formed of both modern and contemporary works. But since 2013 its remit has been to commission and acquire new works under strands including: About the Digital, From the North, and Chinese Contemporary Art. The idea is to tell a more nuanced story of our times, one not dictated from the ivory towers of the art establishment. This impulse is reflected in their current exhibition. Curated by Rowan Pritchard, Art Collection Team Assistant and Graduate Associate, Visibilities: Shaping a story of now, investigates what it means to be visible, by bringing together “works from the Collection to explore and examine who and what is represented in our contemporary collecting.”

In the university’s New Adelphi Exhibition Gallery, space is at a premium, but Visibilities manifests as a focused, thoughtful display that brings works together to address diversity, both in regional communities, and globally. Among the first works encountered is by Albert Adams. His ambiguously striking 1977 drawing Animal Study cuts to the heart of the matter. The animal of the title is evocative of a beast one can’t quite place. It hints at the dangerous and blurred liminal spaces Adams likely found himself occupying in apartheid South Africa, but equally as an artist of African and Indian heritage who spent much of his career in the UK. A new name to me, Adams is an artist whose work I’d like to see more of.

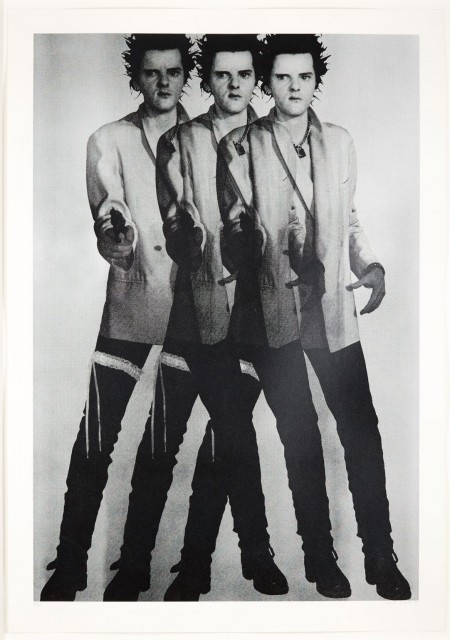

On the opposite wall hangs the altogether more familiar YBA artist Gavin Turk’s Triple Pop – not, you’d think, an obvious choice for an exhibition speaking to reassessing pressing questions of art history. In Turk’s emphasising of established touchstones that flirt with cliché – dressed as The Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious, he is posed to mimic Andy Warhol’s 1963 work Triple Elvis – the artist situates himself in a conversation and tradition stretching back (at least) to Warhol’s day. It’s a neat curatorial inclusion that demonstrates the relative ease with which artists of certain persuasions get to navigate the world while others are so often met with dead ends.

Bolton born Hetain Patel’s animation may similarly have pop culture spidey senses tingling. Canon (2020) sees Patel blend a melange of references that have impacted upon his physicality and identity – including martial arts icon Bruce Lee, Marvel’s friendly neighbourhood Spiderman, and an Indian squatting posture. Although its title refers to his self-selected canon of postures, there is a pleasingly pointed correspondence when we apply Patel’s comments on this work and the bodies in it to the art historical: “The canon actually breaks down… I like that it starts to disrupt its own rule somehow.”

From Bolton we return to Salford, and Mandy Payne’s In Limbo (2017), in which we find the looming presence of Salford Precinct. Rendered in her trademark materials including spray paint and concrete, Payne’s painting foregrounds lives and experiences rarely otherwise granted space in art’s narrative. The piece is bound up and resonates with the traces of people who pass through and occupy such places. And it in-part indicates that, as with gendered and racial discrimination, society must also begin to come to terms with its attitudes to class. Speaking with Payne in 2021, the artist said: “There is an underlying socio-political narrative to my works, indeed class and politics are inextricably bound up in architecture.”

From the stones throw away local to the global, in photojournalist Wu Yue’s images we find unsettling reminders of all our recent pasts. Taken in Wuhan in 2020, to look upon them now is to step back through the collective miasma brought about by the Covid-19 outbreak and catch, with a shiver, a glimpse of the real-life twilight zones we inhabited. Some emerged on the other side and others didn’t, so there is bitter comfort in Wu Yue’s photographs, which present us with scenes of isolation and connection, recent history, and a still uncertain future. But they also show, ultimately, the universality of things – when we look upon them, we reflect on how we all went through this event.

As its title suggests, Visibilities is committed to giving space to perspectives so often previously omitted and overlooked. The curatorial thinking behind it demonstrates well the responsibilities that exhibitions teams – and by extension, art collections – have to a more complex telling of art’s story; not an abridged version, or somebody else’s preferred reading. The exhibition poses and prods at questions that have so recently gone unasked. It restates what Guerrilla Girls knew all along, going some way to redress the balance.

Mike Pinnington

This text is the result of a commission by University of Salford Art Collection

Visibilities: Shaping a story of now Continues until 25 August. The result of a two-year traineeship, it is curated by Rowan Pritchard, Art Collection Team Assistant and Graduate Associate.

Images/media, from top: Wu Yue, Reconnected, 2020. Image courtesy the Artist; installation photography; Gavin Turk, Silver Triple Pop, 2009. Courtesy the artist. Photography by Museums Photography North West; Hetain Patel — “Canon” (Commissioned for Peer to Peer UK/HK)