The New Bend @ Hauser & Wirth – Reviewed

“A wealth of knowledge, care and skill.” In Hauser & Wirth’s The New Bend, Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou finds an exhibition celebrating and extending an artistic, cultural and social legacy generations in the making…

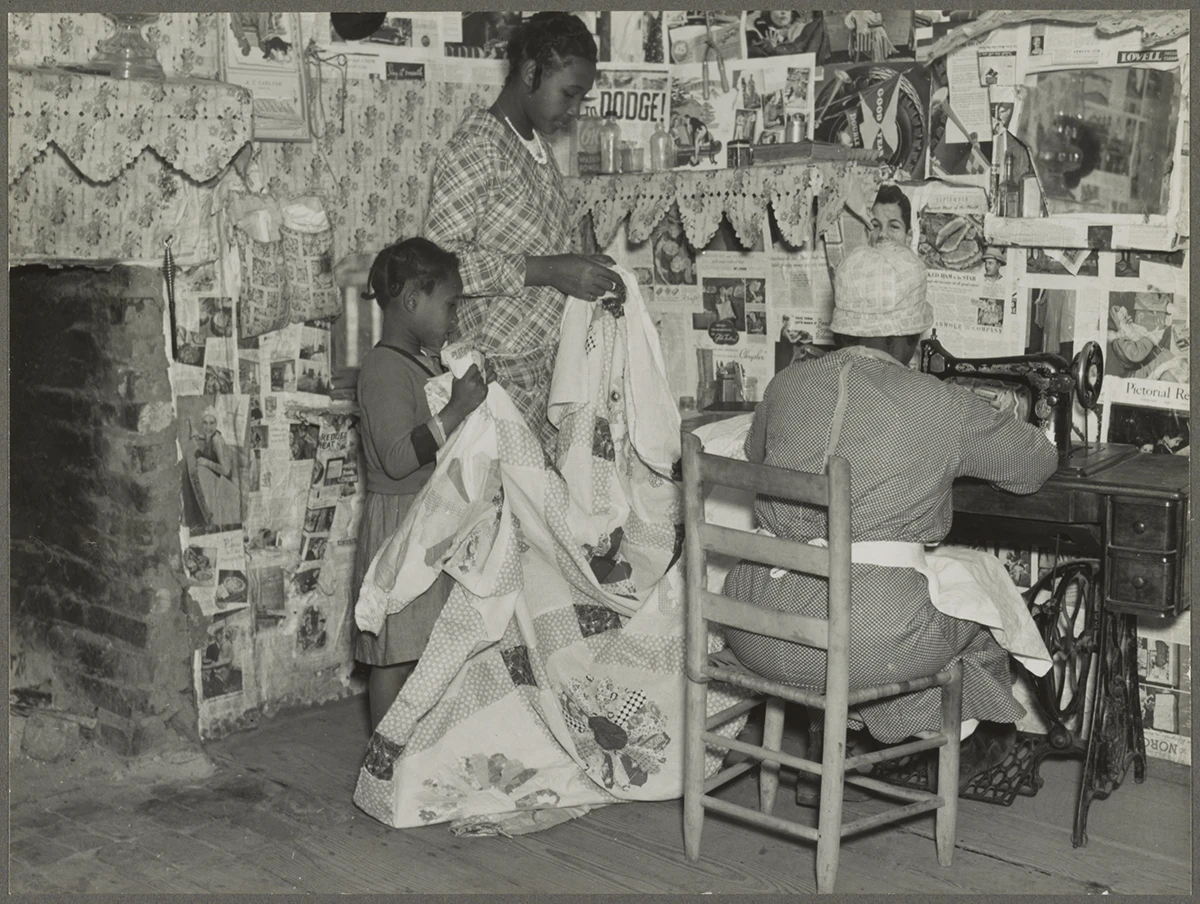

What catches my eye are the hands, small fingers clasping crisp material folds. There is a small child grasping the edge of some fabric, a taller one holding a tuft of the same cloth, and an older woman hunched over a machine, her back taut with concentration. The woman keeps her foot steady on the treadle, her eye looking to the needle keeping time. She is immersed in a mode of map making, a crafting of cloth and gathered scraps sewn with feeling and colour, memory and meaning. The children watch, taking in the measure of each stitch. Three generations gathering the folds of a single quilt; three generations, a wealth of knowledge, care and skill in their hands.

This is a photograph (above) included in the booklet to The New Bend, Hauser & Wirth’s exhibition celebrating contemporary quilting and textile art. Curated by Legacy Russell – a significant figure in art writing, curating and theories on alternative technologies and spaces for Black artistry and being – the exhibition has travelled from LA to Somerset. It is inspired by the work of the Gee’s Bend quilters, an African American collective from Boykin (also known as Gee’s Bend), Alabama, whose artistry in quilt-making dates back over two centuries. A matrilineal art form preserved and passed down to subsequent generations of girls and young women through their mothers, their work has its roots in familial care and communal cooperation, in gendered, racialized and classed labour, activism and ingenuity. Originally created to insulate homes – the quilts were used as carpets, blankets, wall or door hangings in the cold winter months – the creative output of the collective was eventually harnessed to raise funds for the community. Today, the Gee’s Bend quilters are recognised as modern artists as well as artisans, and it is this interwoven legacy that Russell and the twelve artists exhibited in The New Bend commemorate as well as innovate.

Overt homage comes from Zadie Xa. In the centre of the sun-lit gallery, suspended on a large stretcher, Xa’s Shrine Painting 2: Western Yellowcedar (2022) gleams like stained glass. Its intersecting hand and machine stitched panels put it into direct conversation with the Alabama-based collective’s quilts, which are often characterised by a cuboid or pyramid arrangement of material blocks (respectively called a ‘housetop’ or ‘rooftop’ pattern) that work from the centre to the outer row. Here Xa amalgamates both geometries, creating contrasting densities of triangular and rectangular colour. The seamed blocks elude the eye in their precise form, as what appears to be one solid cube of orange is actually a tessellation of peach and red; or what looks like a panel of blue is, upon closer inspection, four squares receding into distinct shades. What Xa enshrines in this meticulously crafted and craftily conceived hanging is the collective’s eye for uniting unique palettes of colour with asymmetrical formations.

Such cuboid echoes can be found in the work of Ferren Gipson, but with a twist. Virtually overlaying two separate works – a rust-coloured vinyl formation of interlocking squares titled Seeing (2022) over a more typically quilted or woven hanging made of stretched linen and silk called I am not a machine (2022) – Gipson plays with the sense of space that quilts create when utilised practically and looks back to their original purpose as wall hangings, spatial dividers and partitions. Challenging what is stereotypically associated with quilting both formally and materially, Gipson’s overlaid works forge a dialogue about the techniques and possibilities that the art form affords. Juxtaposing silk and cotton with vinyl, the histories of these diverse and variously prized materials come into awkward contact, seeing Gipson again interrogate the materials and technologies considered unworthy of creating and constituting ‘art’. Draping the skin-like vinyl of Seeing over the silky skein of I am not a machine, the modern and the traditional converge whilst essentially sharing the same technological DNA.

Gipson isn’t alone in simultaneously celebrating and participating in the Gee’s Bend quilters’ ability to innovate textiles and art in general. Both Rachel Eulena Williams and Sojourner Truth Parsons question the division between painting and quilting, between ‘art’ and ‘craft’ in bold works of their own. Creating paintings that brightly reference the strips and slips of marvellous colour found in the quilts of the artists of Gee’s Bend, Parsons powerfully demonstrates that a quilt like a painting can be both an object and a landscape, a thing to behold and belong to at once. Her paintings dominate the walls, their still and sombre shafts of blue, pink and green arresting the eye as much as they envelop the body. Like Parsons, Williams staggers colourful fragments and striking shapes in a collagic fashion, but takes this further to deconstruct all sense of formal construction. Her work, Red, Invisible, Blues (2022) has a jazzy, staccato effect and uses an assemblage of wood, rope, canvas, polyester and acrylic that breaks the constraints of the frame, drawing the eye to its place and position on the wall. In repurposing unconventional materials, Williams, as with other artists here, celebrates the artistry and ingenuity at the heart of African American quilting. Her Swing in Protective Style (2022) – an actual swing made of silk textiles, cotton rope and acrylic – joyously and movingly celebrates the craftsmanship of Black individuals the world over by alluding to multiple ancestral forms of creativity: weaving, quilting and hair braiding. Plaited into its design is not only the joy and pain of such artistic and socio-political histories, but the perseverance and resilience of those at the heart of them.

As this exhibition indicates, it is women who are central to the preservation, continuation and innovation of such artistic legacies and achievements. Looking back to the three generations of Gee’s Bend women in the photograph, Qualeasha Wood and Dawn Williams Boyd both address issues pertaining to Black womanhood, queer and cis femininity, and bodily autonomy. While Boyd uses traditional techniques to narrate the lived experience of Black women, Wood explores the same themes but through the more modern technology of the digital jacquard loom. In Boyd’s work, The Right to (My) Life (2017), a lattice of hand-stitched signs and faces forms a pro-life protest and blazes behind a tableaux of a young Black single-parented family of three. The central figure, a pregnant woman, clutches her stomach while her young son protectively folds into the side of her body and touches the unborn bump. To the left of them, her daughter sits cradling a doll; her eyes cast down, her demeanour solemn. There is a quiet familiarity and knowing uniting this small family unit, who express a togetherness as much as they grieve apart. To the right of this trio, a white woman steps out of a chauffeur driven car. The contrast could hardly be starker. The sure but silent affectivity of the piece loudly emphasises the gross inequalities and inequities at power in the world. Prejudice vociferously booms behind, wealth evades such condemnation from the side, and the realities of maternity and being Black in the US sit in the centre of it all. By using a child-like mix of bright patterned materials and textures with diverse quilting and sewing techniques, Boyd further complicates the narrative and throws into blinding relief the debates around who and what has a right to life. In a post Roe vs. Wade world, Boyd’s rainbow-coloured story quilt of a work speaks up for, as much as it recreates, the bodily experiences and positions of Black women and their children.

Qualeasha Wood’s Ctrl+Alt+Del (2021) approaches similar themes of maternity, (queer) femininity and bodily autonomy but from the dimension of the digital. Her work draws together a host of historical influences and cultural vocabularies – from Renaissance religious iconography and composition through to digital interfaces, programming, coding and virtual expression, Wood shows that Black femme identity is fashioned and filtered through multiple frames and planes of reference. Centralising digitised versions of herself against a backdrop of a cross and a nimbus of gold haloed around her computerised head, Wood blurs saint and sinner, Madonna and Christ, the human and the sanctified divine. Using emoticons of Black putti and innumerable opened tabs intersecting her own digitised form, the artist puts the machine in the Ex Machina. Impressively ameliorating the traditions of textiles through digitisation, Wood complicates received notions of womanhood, embodiment and technology, and reiterates its potentialities as much as its flat-screened limitations. As the dissolving cruciform figure in the lower half of the work shows, future technologies can erase as well as uphold the traditions and designs of the past. Simultaneously looking at us and herself from the surface of the weave, it is clear that Wood is aware that these evolving technologies and artistic practises can make, break and remake an individual and collective sense of selfhood.

Looking at these two artists, two distinct generations, one of the youngest displayed opposite the oldest in this triumphant show, it is clear that the legacy of the Gee’s Bend quilters remains in the safest and most creative of hands.

Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

Hannah saw The New Bend at Hauser & Wirth, Somerset. The exhibition ran 28 Jan – 8 May, 2023

Images: Dawn Williams Boyd The Right to (My) Life 2017 Mixedmedia © Dawn Williams Boyd Courtesy the artist and Fort Gansevoort Photo: Ron Witherspoon; Jennie Pettway and another girl with the quilter Jorena Pettway sewing a quilt, Gee’s Bend, Alabam, 1937. Photo: Arthur Rothstein; Installation views, ‘The New Bend’ curated by Legacy Russell, Hauser & Wirth Somerset, 2023Courtesy the artists and Hauser & WirthPhoto: Ken Adlard