Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV – Reviewed

Trickster or sage? A film about father of video art Nam June Paik looks to bring his enduring genius to new audiences…

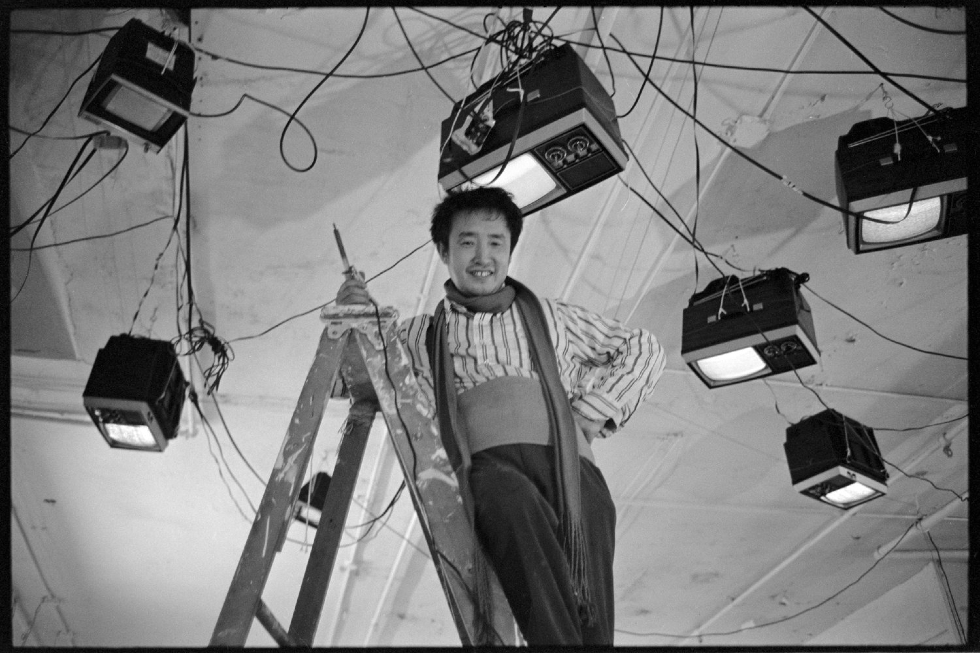

It’s impossible to overstate the influence and importance of Korean artist Nam June Paik (1932–2006). In her first feature, subtitled Moon is the Oldest TV, director Amanda Kim lovingly traces and illustrates his story with no small degree of relish. No bells and/or whistles are spared. Actor Steven Yeun reads Paik’s own writings, while it is scored by non-other than Ryuichi Sakamoto. In addition, it benefits hugely – and Kim selects and organises judiciously – from some incredible access to what amounts to a deluge of footage.

From archive and specially recorded interviews, we are introduced to his widow, contemporaries, art historians, critics and family members, and shown how an encounter with John Cage changed the course of Paik’s life and led to an enduring friendship. (We learn, too, of the Kafkaesque nightmare Paik endured in childhood, in which he could speak Korean at home, but only Japanese once on the street.)

His country divided and a growing chasm opening up between him and his father, from privileged beginnings, in 1957 Paik bolted to West Germany, where he studied music, intending to become a professional composer. At that time, he said, he’d believed that “a few geniuses had fallen from the heavens, and they should be German or French.” Attending a performance by John Cage, in which he was one of the few in the audience who stayed until the end, “something strange happened.” 1957, Paik said, was BC: before Cage. “It was really very profound.” A leading figure in the post-war avant-garde, Cage gave the student license to push through boundaries – “the license to be free” as he put it.

Realising then that he “wanted to carve out a different path” he bought a TV – then advanced technology – and opened up the back. He became inspired to be a TV artist. But this freedom, what for Paik is a kind of vocation, really, comes at a cost. His early experiments in art actions are misunderstood, or worse, seen as a kind of side show. But he perseveres – what else can he do? He joins the recently founded international, multi-disciplinary artist saboteur group Fluxus, and we follow his onward journey to the US, where he arrives in 1964 with an ever-multiplying collection of TVs.

Although he wasn’t famous, or even “New York famous”, as someone puts it, he is becoming both well-known and respected in this burgeoning multimedia field. “Successful artists, they impoverish their output by concentrating on marketable style. For me,” Paik said, “it was experiment for experiment… Newness is more important that beauty.” But pioneering vocations don’t pay the bills. He is an artist working in a medium that as yet has no market. We watch, aghast, as he humbly writes letters, asking for money. Paltry amounts to get by, to be able to buy some groceries. On the brink of defeat, and considering leaving America behind, he receives funding in the form of a grant from the Rockefeller foundation, to work in studios with then cutting-edge tech.

He declares that he wants to “shape the TV screen canvas.” As he put it:

As precisely as Leonardo

As freely as Picasso

As colorfully as Renoir

As profoundly as Mondrian

As violently as Pollock and

As lyrically as Jasper Johns

After his time on the metaphorical breadline, it’s genuinely thrilling to be privy to Paik grasping the opportunity to fulfil his visionary ambitions. And to see his prescience clearly demonstrated with projects like Global Groove, a hectic collage of sound and image that bears no little resemblance to our experience of today’s media saturated reality. In Good Morning Mr Orwell, meanwhile, he outlines his belief in the idea that technology, harnessed positively, can cross boundaries, reaching audiences (via satellite) including in Korea and behind the iron curtain, demonstrating his duty to disrupt on behalf of optimism.

But, just like a dodgy old satellite TV feed, it has its share of blind spots. Rarely does Kim dwell to fully contextualise or bask in the profundity of Paik’s work. What, I wonder, will audiences new to Paik glean as they watch him repeatedly attack his piano; traipse through streets with a violin trailing behind him (as bemused, largely disinterested crowds pass by); or sticks his head in a pot of smoosh. More Chaplinesque trickster than sage? It fails, too, to properly situate him in his milieu of provocateurs. Perhaps the problem is a result of assumed knowledge on Kim’s part. Or preaching to the converted. Jonas Mekas, Merce Cunningham and others pop up with nary an introduction, mentioned in the same breath are the likes of Allen Ginsberg.

Those of a certain age or the necessary grounding in the flurry of cultural connotations flying rapidly before them will be on steady ground, but everyone else will have to intuit or take for granted their significance. Unlike contemporaries such as Andy Warhol (who, strangely, doesn’t warrant a single mention in the film’s run time), household names these are not.

Amid such oversights, however, there remains more than enough to recommend Kim’s polished if conventional film. It is at its best when profiling and adding biographical flesh to the bones of this singular artist. It is unflinching as we hear of his financial dire straits, and later, his failing health owing to a stroke. And it is ebullient in conveying Paik’s belief that TV – and other technologies – shouldn’t necessarily produce passive audiences. “I think talking back is what democracy means.” For Paik, then, it’s not as Marshall McLuhan asserted, that the medium is the message; the medium is simply the medium, to be done with as we choose.

An aside: by luck or judgement, the film’s release coincides nicely with the V&A’s Hallyu!, a major exhibition celebrating and showcasing the Korean Wave. Exploring South Korea’s contribution to global popular culture – from cinema, drama and music, to fandom, beauty and fashion – one is in no doubt that the enduring genius of Nam June Paik played its part.

Mike Pinnington

Nam June Paik: Moon Is The Oldest TV is in cinemas and available to stream now