Opinion: Who are you calling insignificant?

It was with grim interest (and practically open-mouthed) that this week we read that the Telegraph had lazily declared Liverpool, more or less, a cultural backwater, in an article written under the artificial pretext of a Liverpool versus Glasgow face-off.

“Let us imagine for one moment that this is actually a prize awarded to the most culturally significant city. Who would come out on top?” the Telegraph article asks with glee, pitting one great city against another. Of Liverpool’s cultural status, it declares: the city “falls short, with no art galleries, dance companies or opera houses – at least not any that carry any great significance beyond the North West.” We could almost hear a collective sigh echoing from both cities. It’s tiring having to deal with such rubbish.

It is unclear exactly what the author’s criteria for “significance” was. But we found it particularly interesting – and illuminating – that it began with the throwaway “For a moment, I am going to step outside of my London bubble.” Had they ever visited Liverpool at all? Reading like a flagrantly partisan blog, the piece fails – is perhaps unable – to see or give another perspective. The thrust of any well-made argument falls apart as soon as the decision is made not to mention any of Liverpool’s galleries or museums. Which begs the question: was their concern that, under closer scrutiny, they would give the game away, proving their theory laughable?

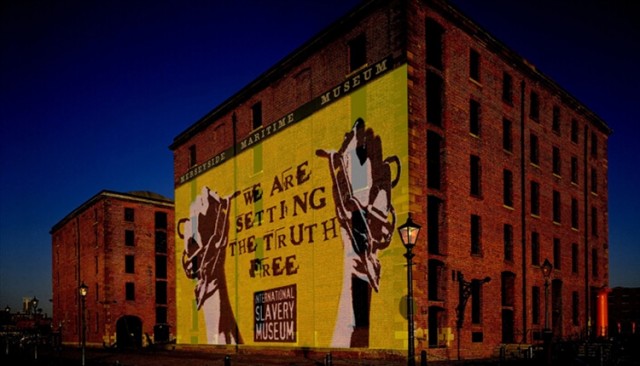

This is not the first time this has happened, of course; our initial reaction was that this read as very outdated – like something written about the city in the 1980s, when national media saw Liverpool as more than fair game. We’ve seen our fair share of ignorant journalism. We remembered how, in 2020, there was a call for the establishment of a national slavery museum to recognise the UK’s part in the slave trade. All well and good. The only thing is, an International Slavery Museum already existed: in Liverpool, and has done since 2007.

Never mind that the city is also home to a Tate (holder of the national collection of British art from 1500 to the present day, as well as modern and contemporary art from around the globe); Bluecoat, the UK’s first arts centre (and perhaps the first arts venue in the North-West to stage an exhibition that specifically focussed on work by Black British artists); an embarrassment of riches on William Brown Street (including The Walker Art Gallery, national gallery of the North) and the largest festival of contemporary visual art in the UK (Liverpool Biennial).

Then there’s FACT (Film, Art & Creative Technology), who have been exhibiting critically acclaimed artists experimenting with film, moving image and new tech since 2003 (including significant solo shows by French New Wave pioneer Agnes Varda, and the father of video art Nam June Paik); Open Eye, one of the oldest dedicated photography galleries in the British Isles and a pioneer in socially engaged work. Exciting presentation spaces like these are supported by annual showcases and commissioners like Africa Oyé, Liverpool Irish Festival, Liverpool Arab Arts Festival, DaDa (Disability and Deaf Arts), Writing on the Wall Festival, Homotopia, plus art production spaces like Baltic Creative, The Royal Standard, CBS, Bridewell Studios, and producing theatres, the Everyman and Playhouse, who support new writers and theatre makers. The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic on Hope Street is home to the UK’s oldest continuing professional touring symphony orchestra, led in the past by Sir Charles Hallé, Vasily Petrenko, Sir Malcolm Sargent, and now Domingo Hindoyan (formerly of The Metropolitan Opera and Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin).

There are clearly too many to mention, which is why so many undergraduates moving to the region for its four universities stay and call Liverpool their home, setting up their own creative projects and businesses. But if the only cultural offer Liverpool had to its name was the International Slavery Museum, it would retain its status as a relevant and significant city – culturally, socially, and politically.

When we started this publication, Liverpool – then a recent recipient of European Capital of Culture, home to Tate Liverpool and the first to host the Turner Prize outside of London – had a mature, ambitious, and lively arts scene. As such, we felt it could benefit from a critical friend in the form of The Double Negative. If something was great, we’d say so. Equally, if it fell short, we wouldn’t be shy about it.

Importantly, there was more than enough cultural output on our doorstep to support a new publication of this kind. To this day, we can write about a new exhibition, stage production, public artwork, gig or concert, festival, live art event, book launch, open studios… The list goes on. Despite bigger threats to the city’s cultural offer (like the pandemic, austerity, Brexit, and funding cuts to the arts) the city’s galleries remain ambitious and outward looking, and, as such, there are no signs as yet that we are at risk of exhausting our subject matter at The Double Negative. We never take this for granted, and articles like this fuel our desire to shout about and analyse what goes on here.

So: obtuse ignorant ramblings of somebody who has never set foot off the train at Liverpool Lime Street, or simple good old-fashioned Liverpool-baiting? We don’t know which is worse; either or both would be as revealing as it is embarrassing for and unbecoming of a national newspaper. It seems deliberate, as a quick Google would quickly put this argument to bed. What we do know, however, is that such poorly informed opinion only serves to highlight the necessity of critical voices outside of London: whether from Liverpool, Glasgow, or elsewhere, but especially from small working class cities who specialise in fantastic arts and culture. It reaffirms our importance; and, ironically, the provincialism of a London-based writer.

Mike Pinnington (and Laura Robertson)