Julie Cassels: We View Things Differently Now

Pre-digital, pre-Instagram and the rest, what were you doing when you looked at a photograph? This is a question posed by artist Julie Cassels, whose practice interrogates our relationship with making – and looking at – photographs through the ages…

What are you doing when you look at a photograph? Are you conscious of how you engage physically, for instance? Within living memory, there would have been a more obvious answer, a process; a tangible act of leafing through an album. Even before you got to do that, it would have meant popping to Boots, or Max Spielman, to collect the photos and negatives; only then could you settle down with anticipation, to see how they’d turned out. I still have very clear memories of doing this, right down to the street and shop I’d go to.

But today, these old rituals are increasingly rare; and yet, our love of photography – of taking and looking at photographs – is unbowed. How we do this has changed dramatically; more often than not, it is via a digital, rather than analogue platform. Indeed, whether intended for Instagram, Facebook, myriad other social media (or, frequently, never to be viewed at all), it’s estimated that 1.2 trillion digital photos will be taken worldwide this year. Writing in 1977, Susan Sontag said that “To collect photographs is to collect the world.”[1] “Photographs really are experience captured,” she continued, “and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.”

Even the iconic Sontag couldn’t have foreseen or anticipated so startling a revolution in access, though – or our increasingly voracious appetites. Decades on, the camera(phone) – and its heightened ability to ‘collect the world’ – remains a magical thing. But how has reception changed in that time? As we find ourselves swimming amid an ever-flowing river of images, beyond the numbers, how has our relationship with them changed in the intervening years?

Such questions and this emphasis on the act, on how we consume images, has always fascinated Manchester-based artist Julie Cassels. I visited her last year at Rogue Artists’ Project Space, to discuss her exhibition We View Things Differently Now, when she confessed to an “obsession” with photography. The exhibition’s title, she told me: “has to do with the way in which how we view imagery has changed.” Not so much how we read it socially, culturally, or politically (although these are all factors nonetheless), but “at that physical ‘what were you doing decades ago when you looked at a photograph?’” It is, she continued, “about the performance of viewing, rather than the global ‘what was photography like?’”

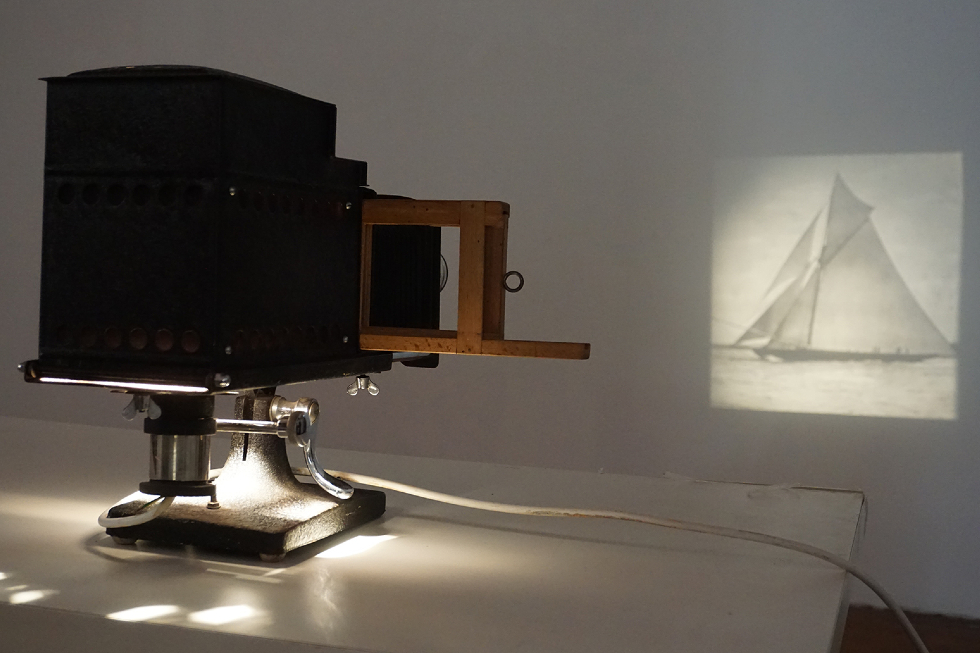

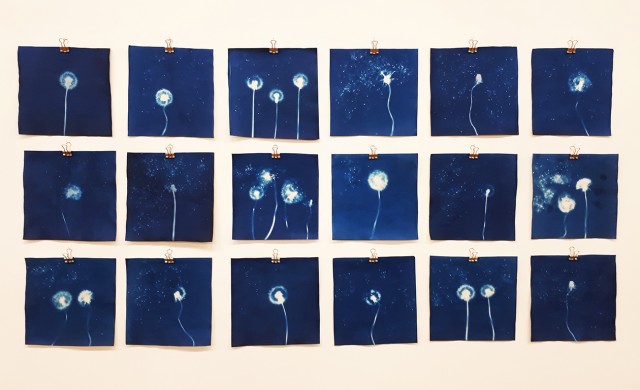

In a very literal way, the exhibition set out to capture and foreground processes; a ‘how we used to live’ of photography. The “technological developments, social pressures and economic considerations have changed [habits]”, says Cassels. To illustrate and emphasise these changes, she has gathered together and displayed – among other things – old found slides, images made using the wet plate collodion process, and stereography, including her own work along with historical examples. It makes for some fascinating juxtapositions, and it’s not always easy to tell which is which. As is the case with a set of her cyanotypes hanging on the wall (below) – mining a more-or-less unchanged technique first popularised by botanist and photographer Anna Atkins in the mid-19th Century.

No mere archivist, then, through her own, direct – and deep – engagement with the field, Cassels experiments with and employs photography’s history and its artefacts to demonstrate the interrelationships and materiality of practices through the ages. This acts as a departure point for her own practice, which drills into and pushes at the edges of photography’s possibilities and conventions. She speaks of wanting to find ways of activating the surface of images and asserts that, how photography is presented is, for her, always something to be resolved.

If We View Things Differently Now addresses this question of activating the surface of an image, the exhibition’s title can also be read in a different way, one relating to Aldous Huxley’s experiments with mescaline, recorded in his book The Doors of Perception (1954). In it, Huxley said that mescaline had given him access to the artist’s mind, opening up a new way of seeing. In one passage, he recounts being captivated by the beauty of folds of cloth – in drapery and even his trousers: “Those folds in the trousers – what a labyrinth of endlessly significant complexity! And the texture of the grey flannel – how rich, how deeply, mysteriously sumptuous!”

In Huxley, at least in his awareness of textiles (if not the lengths to which he went to form his appreciation), Cassels found a kindred spirit. “When I’m looking at a painting,” she explained, “I’m looking at the textiles.” Everything else, while still there, is less prominent. Peripheral. In her series Seeing Differently, in found books, paintings, and photographs, she has removed all traces of everything other than textiles and clothing. The result can be an eerie one – people are disembodied, reduced to their – often – workaday clothes, in some ways, ghosts of their labour. Afterimages, of sorts, in which Cassels demonstrates her experience of looking, and elevating for the viewer, the haptic power of textiles.

In Someone Else’s Things (above), this is taken further still. Digitally reconstructing rare or obsolete pieces from what she calls ‘remote sources’ – images found online or in textbooks – the artist uses sculptural theory to digitally restore historical objects; here, gloves, clothing and other items are given three-dimensional form. There is something forensic about this line of enquiry. But tactility, and a kind of exhumation is to the fore, too. It’s a form of time travel. What does it mean to reach into the past in this way, to retrieve and revivify, through digital means, what would otherwise have been lost to the ages?

Everywhere you turn, questions present themselves, and from all sorts of angles – be they cultural, historical, or technical. The series Portraits of Fabric (below) puts me in mind, for example, of the way in which director Alfred Hitchcock frequently dwells on the back of his leading ladies’ heads (see especially Vertigo and Rear Window), but also his coded palette (prominent in Marnie). It seems a short leap to Laura Mulvey’s theories around the male gaze, explored in her 1975 essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Are these works, which invite us to scrutinise the almost biomorphic folds and creases in the cloth inspired somehow by Hitchcock’s cinematic language?

In fact, Cassels tells me, they respond to Jan van Eyck’s 1433 Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?), with the intention to capture and display materiality as you would a still-life. Although any relationship to Hitchcock is obviously one manifested by my own cultural touchstones (and, perhaps, subconscious), these photographs display and celebrate a sensual, luxurious aspect of textiles to which Cassels is particularly attuned.

Staying with Mulvey, though; in a later essay, addressing our evolving relationship to images, she writes that “new technologies have given a new visibility to stillness,”[2] thus serving to highlight the fixity of celluloid. This dichotomy is explored by Cassels in a body of work which brings together still and moving digital imagery. Looking back to Eadweard Muybridge, and the link between stop-frame photography and cinema, shown side-by-side, these works emphasise the active properties of ‘moving pictures’ versus the embalming of a moment in time (and life) implied by still images. The result is one akin to dissonance, and yet also complementary, producing an almost uncanny response in the viewer.

There is something of this quality in each of Cassels’ ongoing series. Taken together, and in the most practical understanding, her practice combines art and photographic history, sculptural form, photographs, and textiles. Distinct, tangentially-related enquiries – about the quality and visibility of textiles, still photography and film, 2D and/or 3D, the onset and impact of digital technologies – produce a coherent whole. There is an indelible investigative through-line, meaning that the work can be approached from a variety of perspectives and entry points. As Cassels continues her inquiries, it will remain one worth following.

[1] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1977) 1–2.

[2] Laura Mulvey ‘Stillness in the Moving Image: Ways of Visualizing Time and Its Passing’, in Saving the Image: Art After Film (Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University, 2003) 78–89.

Mike Pinnington

Julie Cassels’ work is included in the Manchester Open Exhibition @ Home, Manchester

All images courtesy the artist