The Word On The Street: Liverpool In Literature

“From the situatedness of the city through to the mediated experience of the symbolic plane.” Anthony Ellis takes a look, via various Liverpool streets and eateries, at the weaving together of literature and place…

In Kirkby, Liverpool, the unsuspecting wanderer can find themselves in a corner of the city that has higher – literary – pretensions. Here, amongst the suburban semis and evergreens, the streets are named after a coterie of English literary greats: Shelley Court, Shakespeare Avenue, Coleridge Court, Dickens Close, and Wordsworth Court.

As far as I can ascertain, there is no particular rationale for these street names. Like so many constellations of place, the system of street nomenclature appears arbitrary but, nevertheless, not without some significance. It brings a whole new meaning to the phrase, ‘the word on the street’.

It doesn’t stop there. In the city, there are various eateries and shops that take their name from classic texts. Viewed through the lens of the literary work, these establishments have a different feel: the book may seem a wellspring of accidental and chance observations about the space of the city and the lives that run through it. It is the realm of the spatial-imaginary: fantasies that mark the passage from the situatedness of the city through to the mediated experience of the symbolic plane.

The first sandwich shop I ever frequented in Liverpool was named Shirley Valentine’s (top), after the famous play and film by Willy Russell. There was no apparent connection between the shop and the theatrical work but the name seemed to be successful as a marketing gimmick. Truth be told, I only went a couple of times but I did notice that it changed its name to Taste of the Underground a couple of years ago which, as far as I’m aware, has no literary pretensions.

The Russell play is about class and patriarchy, with Shirley upping sticks and moving to Greece in response to her humdrum life. A student I taught at university came from Greece. I once asked what had drawn him to Liverpool as a place to study and he replied that his Mum was from Liverpool. I did the age maths and it added up: his Mum might well have seen the movie and decided to get the next flight to Mykonos. I never asked about it, for obvious reasons, but it seemed likely. Who says art follows life: life can follow art too.

A Passage to India on Bold Street is a well-known establishment that most Liverpudlians have stumbled upon at one time or another. I’d never read the book and so decided to take a look, after noticing the restaurant. The story unfolds across the backdrop of the British Raj and the racial tensions that were present between India and the British, with the central Indian character, Dr. Aziz, falsely accused of sexually assaulting a young British schoolmistress, Adela.

Its author E M Forster is able to explore various aspects of the colonial era through the story, with detailed and intricate passages that set off along unexpected trajectories, reflecting on a multitude of experiences and spaces. As I mention above, when reading a book, in the context of a shop or restaurant, it seems there is a constant stream of references that could be linked to the life of a place and the surrounding area:

‘As soon as they had exchanged this admission, a wave of relief passed through them both, and then transformed itself into a wave of tenderness, and passed back. They were softened by their own honesty, and began to feel lonely and unwise. Experiences, not character, divided them; they were not dissimilar, as humans go; indeed, when compared with the people who stood nearest to them in point of space they became practically identical.’

Along Smithdown Road, on the south side of the city, another eatery references a literary big gun, 1959′s Naked Lunch (William S. Burroughs). The novel’s loose story revolves around the main character, William Lee, as he makes his way through a hazed urban landscape on a multitude of mind altering drugs. The text has a non-linear approach, with no clear plot emerging through the multiple vignettes, and so it can be challenging to follow but, of course, that structure is a key element of the work.

I have eaten at the Smithdown Road version and enjoyed it. It does a good breakfast menu and I tried the Eggs Benedict. I couldn’t notice any obvious reference to the book, other than the name. It’s a part of Liverpool that has a melancholic feel, visited at certain times of the year.

It’s worth noting, at this point, that Smithdown Road is quite a distance from the other eateries listed here. A walk between the other four establishments takes less than an hour but to get out to Smithdown takes a while longer. That said, I wasn’t necessarily proposing this network of urban literary signs as a walking tour and think it would be as worthwhile visiting them one-by-one, especially if you plan to eat.

This photograph of Starbucks on Brownlow Hill always causes a degree of consternation when I deliver a lecture on the subject. The complaint is that the eponymous coffee chain isn’t specific to Liverpool and so it shouldn’t warrant a mention. They have a point, but a globalised chain does offer a point of contrast. For those who have not read Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s classic story of nineteenth-century whaling, Starbuck is a central character:

‘Starbuck was no crusader after perils; in him courage was not a sentiment; but a thing simply useful to him, and always at hand upon all mortally practical occasions. Besides, he thought, perhaps, that in this business of whaling, courage was one of the great staple outfits of the ship, like her beef and her bread, and not to be foolishly wasted. Wherefore he had no fancy for lowering for whales after sun-down; nor for persisting in fighting a fish that too much persisted in fighting him. For, thought Starbuck, I am here in this critical ocean to kill whales for my living, and not to be killed by them for theirs; and that hundreds of men had been so killed Starbuck well knew.’

In Liverpool, this reference to Moby Dick has more resonance, owing to the maritime heritage of the city. Whilst whaling was never a significant industry in the port, in the late 18th century there were around twenty vessels registered as whalers, hunting whales for their oil off the coast of Greenland. The Merseyside Maritime Museum has the only known painting of a Liverpool whaling ship, The James, which sailed from Liverpool around 1800.

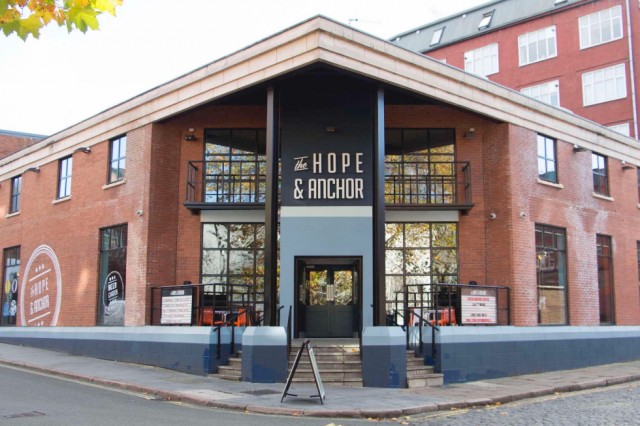

The Hope and Anchor pub on Maryland Street was the last of the literary names that I found, although I’m sure there must be more. I often walked past the building with no idea that this drinking establishment’s name was a literary reference but it stood out to me and, after Googling around, I found this fragment from the King James Bible: ‘Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and stedfast, and which entereth into that within the veil’.

Situated between the two cathedrals, it seems like a well chosen and significant choice of words, on a trajectory parallel to various other intersections of place and language. After all, who hasn’t drifted across town, hop-scotching from one fantasy to another via the rhythmic, street-corner flashcards of street literature? In this fool’s paradise, living the throwaway lines in a ghost-written story of capitalism, moments might be stretched out to hours. On a walk down the shops, the mind-trip triggered by these signs could take days, weeks or years.

Anthony Ellis