“Drawing played a varied, vital role in his practice” – Sickert’s Paper

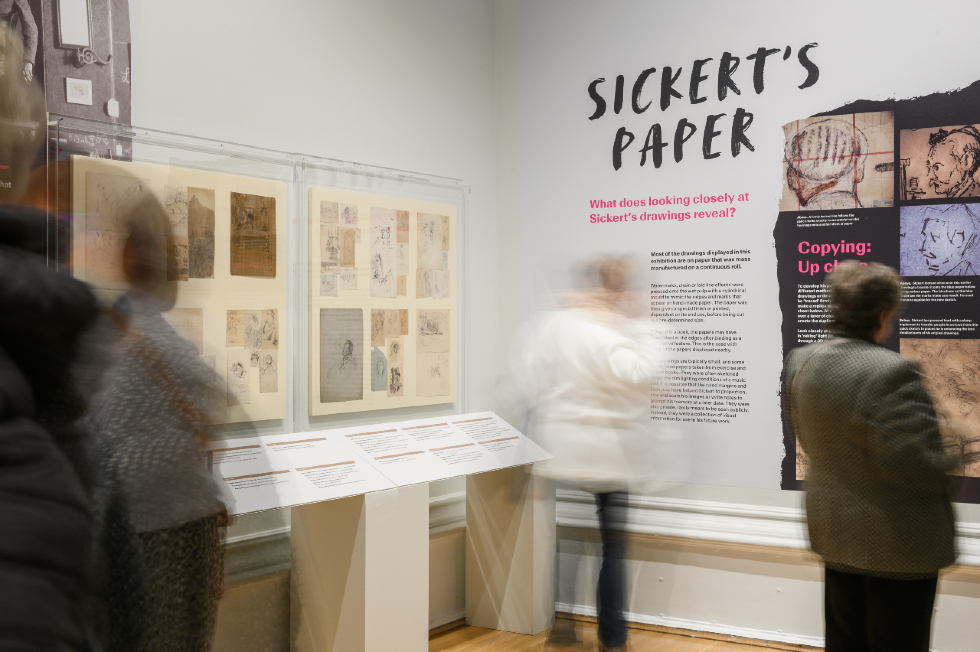

Many of the headlines accompanying Sickert: A Life in Art revolve around rumours of the artist’s links to the Jack the Ripper case. A richer trail of evidence, one could argue, can be found in the exhibition’s selection of the largest collection of his drawings in the world…

The Walker Art Gallery has the largest collection of Walter Sickert’s drawings in the world. It comprises 348 sketches, as well as twelve prints and a copper etching plate by the artist. The collection demonstrates the varied but vital role drawing played in Sickert’s practice. The drawings range from quick on-the-spot sketches made to capture a particular pose or detail, to squared-up final studies for paintings, as well as drawings made as artworks in their own right.

The collection was acquired in 1948 through the Sickerts’ Trust, which was established following the death of Sickert’s third wife, Thérèse Lessore. The Trust set out to distribute the artists’ estates, which included paintings, sketches, personal papers and artefacts. Much of this material was given as gifts to the public collections that had supported Sickert during his lifetime. The Walker was offered several ‘sheets’ of drawings. Recognising the importance of these artworks and the value in keeping them together, the Walker arranged to buy a substantial collection of drawings. A touring exhibition of 107 of these drawings was organised by the Arts Council in 1949. This was the last time the collection was exhibited until the 2021 Sickert exhibition at the Walker.

Sickert held several exhibitions of his drawings, including at London’s Carfax Gallery, between 1911 and 1914. Despite this, the drawings were rarely recognised or discussed during his own lifetime. It was only following the Arts Council exhibition that their importance was finally recognised.

Many of these sketches were arranged by Sickert into groups and mounted together on large sheets, possibly shortly after they were made. He kept them until his death, when they were found in his studio. The original boards to which the drawings were attached were sometimes annotated by Sickert with notes on colour, dates or details about the subjects. Sadly, some of this detail was lost when the drawings were conserved and moved to more stable housing to ensure their survival. The drawings have never been fully catalogued. Some can be identified as relating to certain paintings or periods, but others remain a mystery.

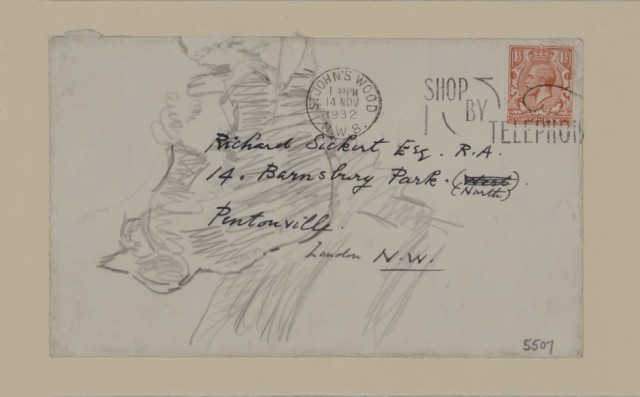

The breadth of the Walker’s collection reveals the considerable variety of paper on which Sickert sketched and noted his observations. Dismantled ledger and graph paper notebooks sit alongside pages from lined exercise books, cheap newsprint and handmade coloured drawing papers. Rent books, envelopes (see A Sleeping Cat, below) and stationery advertisements were all considered appropriate recording material.

Drawing was an essential tool in the creation of Sickert’s finished paintings. Earlier examples tend to be small and hastily executed, suggesting he was a little self-conscious and still working out his methodology. This in turn may explain his later choice of papers, which were bigger, lined sheets.

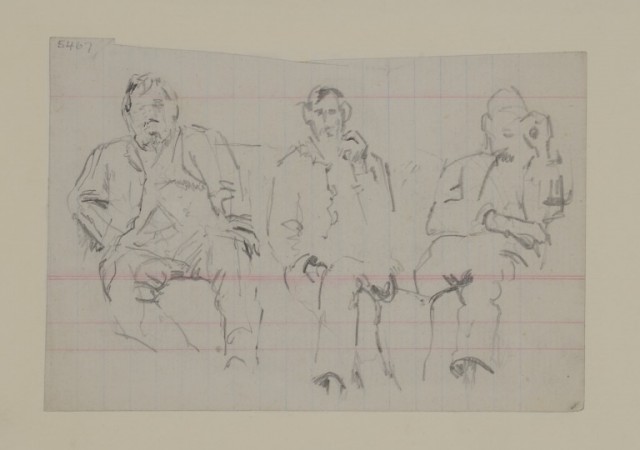

A large proportion of the collection consists of ledger or lined papers, not typically considered an artist’s material of choice. Most artists would see the papers’ rigid, printed structure as a distraction, but Sickert often favoured these bound accountancy books when drawing from life. I’m sure his proportion, size and scale were guided by their coloured vertical and horizontal lines or square graph layout. Perhaps they were also a visual aid in the dimly lit music halls and theatres. In Studies at the New Bedford he used the full length of his largest ledger book to record the linear columns and architectural details, the printed margins guiding his pencil lines. Sickert’s teaching, which advocated the sight-sized drawing technique to create a scaled-down image of the scene in view, seems to confirm this approach.

When recording a fleeting cast of characters on stage and their audience, Sickert’s medium tended to be a soft graphite or black chalk with very little variation of tone. In some instances, a heavier hand and sharper pencil have marked through to the reverse of the sheet, though often a pen is used for this purpose. These appear to be later additions to clarify form. The use of pen and ink was strictly off limits other than in the studio where Sickert seemed to thrive on the limitations of the dip pen, with very little reservoir to hold the ink. One of a series of later drawings shows his use of the medium. He captures the movement of musicians, permitting the pen to run dry and incise the paper before overloading the nib and then allowing the ink to sit on the ‘sized’ watercolour paper, pre-treated to resist water, producing thick, rich velvet lines for contrast.

There are conflicting views as to whether Sickert’s drawings were cut or torn from their binding and adhered to card immediately after completion or at a later date. One possibility is that Sickert added dates and supporting information to the boards quite soon afterwards, which may explain the lack of detail on the drawings themselves. Paper tends to record its history, with multiple pin marks indicating earlier studio use, or with characteristic discolouration showing oxidisation around the edges of book pages. This evidence suggests some drawings had a previous or longer life in their bound state before Sickert re-grouped them. It seems clear, though, that the sketches were grouped in such a way at some later stage to create ‘mood boards’ or scrapbooks of motifs used throughout his life.

Hand-drawn, red grid transfer studies were used throughout Sickert’s practice and teaching. Some of these initial drawings were deemed suitable for scaling-up on canvas, while other studies were grouped into a narrative to help progress a composition. Capturing the essence of his direct experiences on paper is something that came easily to Sickert, but progressing those initial starting points into a composition appears more laboured. When The Piano (below) is examined under raking light, the paper beneath the detail of the right figure shows physical evidence of later mechanical attempts to transpose these visual notes to other sheets. However, it would be wrong to see these as simple image transfers. Sickert sees the initial drawing from life as the primary source, sometimes ‘tracing’ firmly and directly over the original to create a replica incised line on a new sheet below, or working over a layer of chalk or carbon paper to create the duplicate. All these methods represent an attempt to absorb something of the magic of his original life experience without loss or dilution.

Sickert’s papers in the Walker’s collection are for the most part cheap, personal notations, never meant to be seen, let alone exhibited. Sometimes, however, he used traditional Ingres or Michallet drawing papers in blue, brown or buff shades, providing a mid-tone for black and white chalks. One interesting coloured example in the collection shows his use of hand-dyed sheets. In A Seated Figure, an unusual turquoise blue paper shows extreme light fading and points to his experimental use of coloured dyes. Sickert advocated the use of commercial Dolly Dyes to his students to give a prepared coloured surface. The thin, un-sized newsprint he used for this would have readily accepted the hand-applied dye. Some of the colour remains on the protected edges and the back of this drawing, where the chalk medium has offered some protection from light transmitted through the thin paper.

In recording the world around him on paper, Sickert has unintentionally left behind a trail of evidence which, sheet by sheet, is helping us to piece together a greater understanding of his thoughts and working methods.

Keith Oliver, Senior Paper Conservator, National Museums Liverpool

This text was excerpted from the exhibition catalogue Sickert: A Life in Art, with the permission of the Walker Art Gallery. See Sickert: A Life in Art at the Walker Art Gallery until 27 Feb 2022.

Images: Exhibition photography courtesy Pete Carr; A Sleeping Cat; possibly 1932; pencil on off-white machine-made wove paper envelope; envelope postmarked 14 Nov 1932; WAG 5507; Three seated men; date unknown; pencil on ruled machine-made laid paper; WAG 5467; The Piano; drawn about 1921; brown wax pencil underdrawing, iron gall ink and incised line on wove paper; WAG 5411