Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth

What are the aesthetics of investigation, and how might they be developed? Here, in an exclusive extract, authors Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman discuss how groups such as Forensic Architecture are addressing the issues at hand…

Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth seeks to make the encounter between the two terms ‘aesthetics’ and ‘investigation’ larger than the sum of its parts. This meeting point is productive because it shifts and expands both constitutive elements. These words, with their many entailments, begin to work into each other and to figure out new potentials in each other. What we mean by aesthetics and what we understand as investigation then changes.

Aesthetic investigations have a double aim: they are at the same time investigations of the world and enquiries into the means of knowing it. This means that they seek accountability both for events and for the devices with which we perceive them. They deal with the production of evidence while questioning and interrogating the notion of evidence, and with it the cultures of knowledge production or truth claims that it relies upon. They engage in the presentation of facts while being aware of the way each presentation, indeed each media form, can distort the very facts they produce. They seek to establish claims to truth while criticising the institutions of power and knowledge with their monopoly over the mechanisms of truth production.

The media technologies of artificial intelligence, satellite images, social media platforms, smart cities or facial recognition cameras are not neutral; they are products of specific political and historical contexts, with inbuilt biases, opacity, partiality and illegibility and have the potential to enhance discrimination and domination. These biases may not only be those that entrench existing social norms, which have to be fought and reworked, but also those that are particular to specific media forms. These might be particular idiosyncrasies or predilections. They might texture or produce information in certain ways. Some of these features might even be useful in some context.

Using the technology at our disposal, we try to do two things. The first is practical: to employ it as an aid and a context in investigations, presentations and dissemination of data and ideas. And the second is critical: to use the occasion of its employment to offer deep introspection into – or critical self-reflection on – the way such technologies are conceived and operate. This could include investigations into the histories of power that gave rise to them, the biases or tendencies internal to them and the present abuse into which they might be incorporated.

The premise here is, however, that critical examination of specific technologies can often best be achieved through employing and reworking them. It is through critical use, and in practice, that contradictions, biases and limitations can be most fully identified, understood and, when possible, exposed. Every investigative use of, say, satellite photography must acknowledge its military history and ‘resolution biases’ (did you ever notice some parts of the world are available only in low resolution and wondered what happens there under the veil of blur?) as well as limitations of access (people in some places have no access to these services).

Likewise, a critical employment of machine learning and artificial intelligence can try to achieve the same. Forensic Architecture may be using machine learning to help sieve through and triage an ever-increasing amount of video evidence circulating online, but it also uses the occasion to try to shed some light on the computational processes underpinning them that are otherwise often opaque and unaccountable. In short, ‘investigative aesthetics’ uses technology, but interrogates the politics of the very technology it uses; it uses multiple platforms to represent things publicly, but queries the limits and politics of these fora of representation; it involves knowledge production while keeping a critical eye on the power–knowledge nexus.

As such, investigative aesthetics has not given up on its roots in critical theory and is not turning to the positivism of old. It remains suspicious of terms such as ‘fact’, ‘evidence’, ‘truth’ and ‘knowledge’, but seeks to reframe and tease them open rather than abandon them. They are repurposed and reused in a way that yields the productive payload of critical insight. Drawing on work undertaken in recent decades in areas such as media theory, critical environmentalism and science and technology studies, it mobilises both meanings of the term ‘fabrication’ – making of, and making up.

Another important aspect here is that every practice seeking knowledge relies on forms of expertise: in the use of this or that technology, in the attainment and transfer of local knowledge or a certain mode of existence, in access to discourses of politics or law, in experience of political activism and so on. Investigative aesthetics does not seek to flatten out expertise and experience, but to network them in a democratic fashion; that is, to recombine their different forms. Recognising polyperspectivity can be a way of bringing together forms of knowledge and experience from multiple sources.

Such work seeks to develop a methodological diagram in which investigations are undertaken through a set of collaborations between those belonging to different fields and practices. It combines people’s direct experience of an event with the traces left in inert or active matter as they can be recognised by computational codes and interpreted by technologists. There are substantial ethical questions around the adequate formation of such alliances. A primary principle is that it is essential for them to be led by the people on the front line of struggle – hence an emphasis on learning as a prerequisite of such investigation.

The ‘epistemic communities’ that come into being through investigative aesthetics include groupings that are not solely human, but also recognise and find ways to work with their ecological co-composition with plants, minerals, animals and multiple technologies. This in turn calls for investigation to be undertaken in and alongside those places designed to be tuned to signals of different kinds: the laboratory, the field and the studio.

Further, truth and aesthetics need to find different modes of coexistence. In doing so, investigative aesthetics expands the sites of truth telling – from the courtroom, the university and the newspaper, to the gallery, street corner and Internet forum. Each such site requires multiple kinds of transversality to reform relations between groups, practices and sensory objects and surfaces, and indeed necessitates conjunctures between different knowledge cultures, some of which need to be treated with caution.

Amidst this mix of sites and procedures, this decentred and democratic formation of knowledge, capacities to engage with the truth, and to find means adequate to addressing it – that also take into account the ways it can be supressed, produced and fabricated – can be brought to bear on contemporary realities in a way that allows us to move towards understanding how the present world, with its layered crises, can be tested and perhaps reworked.

This text was excerpted from Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth by Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman with the permission of the authors, and Verso Books.

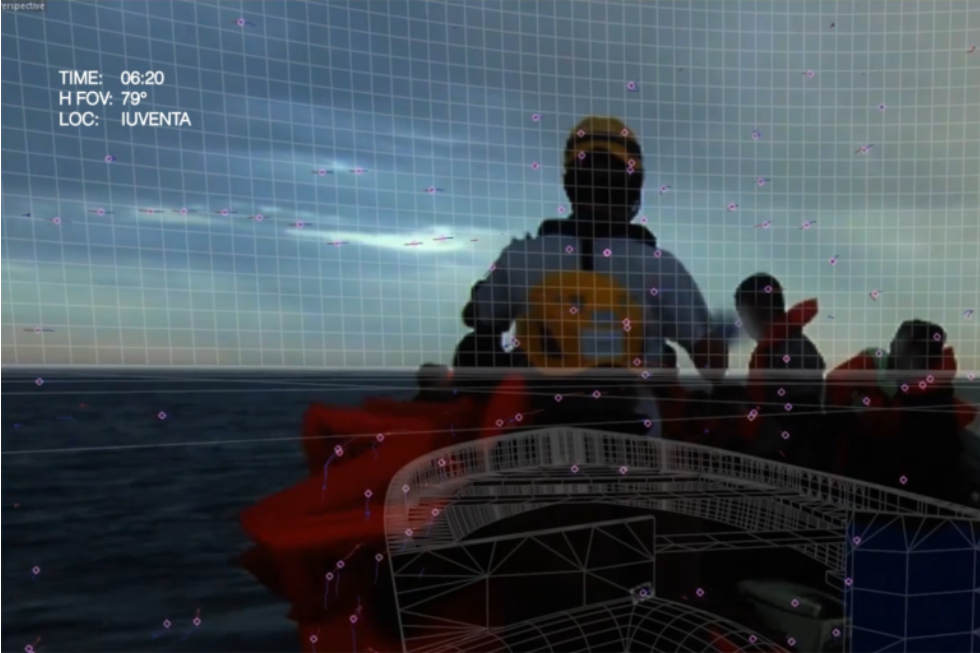

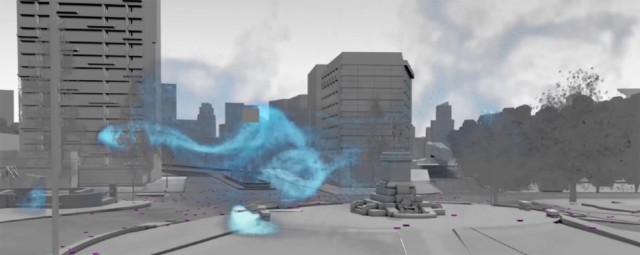

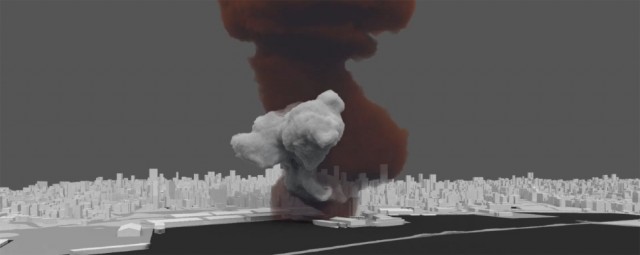

Images: Still from The Seizure of the Iuventa, 2018 © Forensic Architecture / Forensic Oceanography; Still from Tear Gas in Plaza de la Dignidad, 2020 © Forensic Architecture; Still from The Beirut Port Explosion, 2020 © Forensic Architecture (with Mada Masr). See the Forensic Architecture exhibition Cloud Studies, @ The Whitworth Gallery, which continues until 17 October