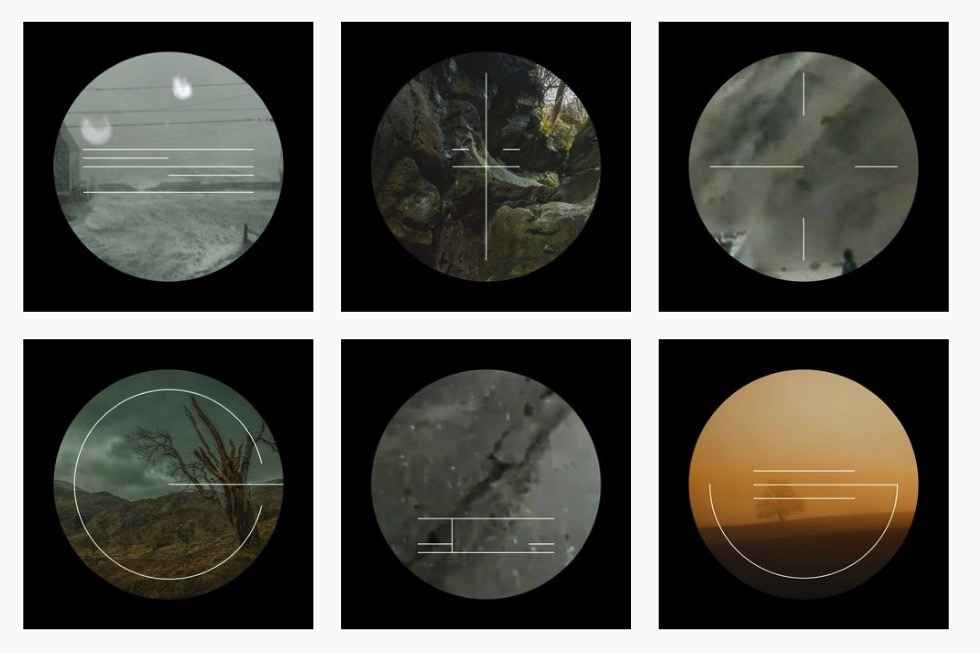

Ghosts of The Great Outdoors™

The first ever West Coast Photo Festival launches this week, commissioned by Signal Film & Media to explore (and interrogate) the West Coast of Cumbria. In a new essay, Jacob Bolton ruminates on Mishka Henner and Vaseem Bhatti’s major exhibition for the festival, Energy Goast, and specifically, the manipulated, synthetic spaces of the Lake District…

I: The Lake District is a Haunted House

What’s natural about the Lake District? For years its valleys have been continually drained and treated with lime to stop moss spreading up the hillside.[1] Its minerals have routinely been ripped out the ground for building and industry: granite, slate, copper, lead, zinc, iron, barytes, graphite, tungsten, arsenic, diatomite. In the medieval era, forests were aggressively timbered to power smelters; newer forests were managed through the process of coppicing, strategically cutting young trees to the ground to stimulate growth. This terraforming stretches much further back than the medieval: pollen records taken from samples at the bed of Lake Windermere show that the swamps that once spread across the land were cleared by the Norse, and that the forests of oak and hazel were clear-cut. It’s far from untouched — it’s a synthetic space, a kind of ruin, one haunted by histories that are continually suppressed through the careful construction of an image of an unspoiled ‘Great Outdoors’. The Lake District is a haunted house.

‘The Great Outdoors’ is not so much a place but a psycho-spatial configuration of landscape, a mode of projecting emptiness onto a space, an emptiness to be filled through hiking, camping, climbing and kayaking. It’s equated with self-realisation and becoming: the National Parks Trust is currently running a campaign with the slogan ‘Be More Outside’, an echo of the rhetoric on which the National Parks were first founded, on the imperative to, as it were, Be More. Appealing for the formation of National Parks in a 1942 Parliamentary debate, Paymaster-General Sir W. Jowitt called for a place where people could “roam about and get some exercise under these conditions… has that not some spiritual value?”[2]

If The Great Outdoors is a realm haunted by latent histories, then the outdoors brand positions itself as a kind of spirit medium, promising connection with a realm that it continually seeks to constitute as sublime. The outdoors brand turns what is not indoors into The Great Outdoors™ through marketing campaigns that promise you that it, too, can be Yours — providing you have the right boots and a breathable Gore-tex waterproof jacket.

This ‘Yours’ is always conspicuously divorced from questions of the actual commons, of the publicness of land usage and the right to inhabit. In the US, sloganeering around ‘preserving the wilderness’ denies the genocides that took place for the idea of a wilderness to even be a possibility. In the early 1500s, settlers in America destroyed agricultural land kept by indigenous people in America at such a scale that it triggered a rapid increase in carbon sequestration, causing a planetary ‘little ice age’ that lowered temperatures throughout the planet for over 100 years, an event that some date as the start of the geological era of the Anthropocene[3]. This resulted in some European towns in France and Switzerland being crushed by glaciers (a kind of retributive colonial haunting in itself).

The idea of a land that is ‘Yours’, in need of protection and conservation, is always decoupled from questions of indigenous land rights (nowhere is this propaganda better explored than in Samuel Marion’s thisisours.us). Those that were killed to make the notion of The Great Outdoors™ possible appear only as ghosts, that haunt the language of the outdoors brand as a hollowed-out signifier of vague belonging, on both sides of the Atlantic. Vango, a Scottish-based camping equipment company, calls its newsletter subscriber list the ‘Vango Tribe’, with the claim that “If you like the outdoors, you’re in” (providing you have internet access and disposable income, that is). In the UK, camping and the right to roam are exalted by outdoors hobbyists as an expression of one’s right to inhabit the land. But this rhetoric rarely intersects with struggles for protecting the rights of Irish and Scottish travellers or Roma Gypsies who have been transiently inhabiting the country for centuries — long before the advent of recreational camping. Conservation, as it is paradigmatically presented in colonial countries, is an attempt at the conservation of playgrounds for White bourgeois recreation. The Great Outdoors™ is, ultimately, a White Outdoors.

Appeals to a Great Outdoors™ also disimplicate the land from questions of ownership and privatisation, disarticulating land from any understanding of how it functions as capital. Looking at how the land is carved up and by who points to how the landscape and ecology of the Lake District really functions: as somewhere between asset and infrastructure. Over 55% of the Lake District is the property of small landowners. The National Trust — a privatised, independent company — owns 25%. The Ministry of Defence holds other large portions of Cumbria as training grounds for forces stationed at the bases that line the West Coast: attempts are underway to expand the reach of their training grounds to absorb stretches currently listed as Common Land, a category held by less than 3% of the UK’s surface. Another large chunk is held by The Forestry Commission, the largest landowner in the UK.

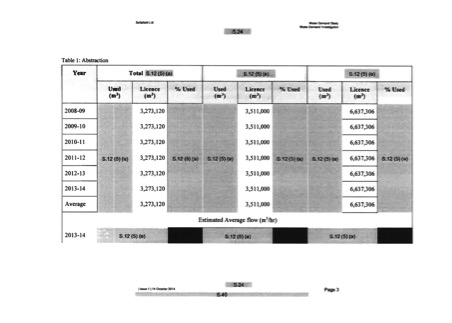

United Utilities own 8%. They also supply water to Sellafield Nuclear Site, the world’s largest concentration of co-located nuclear facilities on Cumbria’s West Coast. The region, somewhat cut off from the rest of the UK through the natural barrier of the Lake District, is a dense weave of infrastructure, military and industrial. A heavily redacted document obtained through a Freedom of Information request indicates that Sellafield is licensed to use 3,273,120,000 of water a year from surrounding rivers, lakes and a water-filled mine (exact rivers/sites redacted). To put this into perspective, this is more water than the entirety of Lake Windermere, the Lake District’s largest lake. The site of Sellafield today is a kind of ruin under construction, existing primarily as a clean-up operation for decommissioning itself and handling higher risk radioactive waste from other facilities in the UK. In a conversation with Mishka Henner and Vaseem Bhatti, the artists behind Energy Goast — the project that this essay accompanies — they speculated that radiation itself is a kind of ghost: something that passes through us, that takes on a life of its own, that inhabits and warps living beings. Radioactive waste is a form of ghostliness, distilled into liquid.

II: Energy Ghosts

The natural landscapes of Cumbria as asset and infrastructure is precisely the view taken by The Energy Coast Masterplan, launched in 2008 as a bid to economically develop the region of West Cumbria. Section 4 of the plan’s brochure lists the region’s ‘Assets and Infrastructure’, placing the area’s capacity for ‘Environment and Tourism’ alongside the region’s ‘Radioactive Waste’ and ‘Decommissioning Expertise’. One striking thing about the document is the variance in its timescales. It projects a prosperous economy for West Cumbria in 2028, 20 years from the date of publication. In order to get to this, it must reckon with the question of nuclear waste disposal, a question that you have to think through in timescales of 100,000 years or more.

One project alluded to in the brochure is a kind of conservational terraforming project par excellence: the construction of a nuclear waste disposal site deep underground, called a Geological Disposal Facility, or GDF — designed to last beyond 100,000 years. Negotiations for the GDF are underway in Copeland, an area bordering The Lake District, although nothing is yet confirmed. You can, if you want, visit their virtual exhibition (I really recommend it), haunted by copy-and-paste silhouettes of faceless attendees, the motionless figures that James Bridle once called ‘renderghosts’. The exhibition touts the GDF as ‘a world-class solution to protect the future’.

The GDF proposes a heavily fortified facility one kilometre underground, initially accessed by trains before being hermetically sealed off. The exhibition offers a 3D tour here, in which you can follow waste as it descends down to the facility, moving from the surface’s here and now to the nowhere and nowhen of the vault. One way to think about the vertical Y-axis of the earth is as a spatialised timeline of the planet in which all times exist at once. Stick with me: beginning in the centre with the molten core (suggestive of the first geological era, the fiery Hadean). Moving out through layers of magma (cooling period). Finally hitting solid rock, in which Jurassic-era fossils lay buried alongside trillions of lifeforms crushed into oil. And us, on the surface, now living out our Anthropocene (above us is space, the future, eventual planetary burnout and dissipation). When we think of the planet like this, the Geological Disposal Facility is a kind of time travel backwards, an insertion of the nuclear present back into our geological yesterday’s Pleistocene. Meanwhile, the process of nuclear energy accelerates ‘natural’ time through explosively releasing energy stored in material, energy that would have taken decades of radioactive decay to disperse on its own.

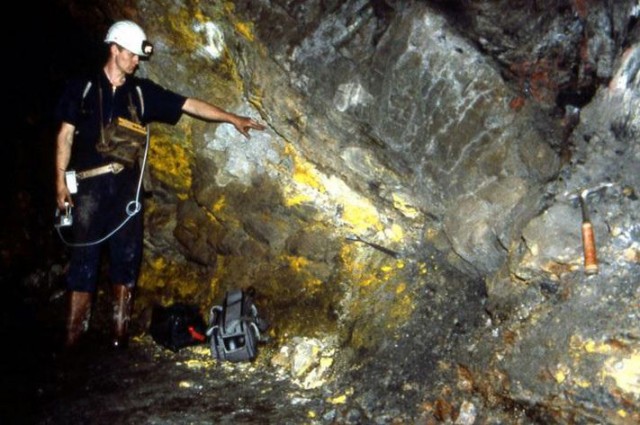

In 1972, some rocks were uncovered in a uranium mine in Gabon, West Africa that showed signs of uranium depletion. As far as scientists knew, the only source of depleted uranium in the solar system was through used fuel from nuclear facilities. People, of course, speculated ancient aliens, relics of a visitation or a buried advanced civilisation.

It turned out that they were fossils of naturally occurring nuclear fission reactors.[4] They resulted from self-sustaining fission reactions that took place 2 billion years ago — roughly half the lifetime of the planet — made possible through higher concentrations of U235 in uranium deposits and the presence of water. To this day, stable fission reactions have not been successfully carried out in laboratory conditions. The fossilised fission reactors are geological ghosts, nuclear hauntings of the Precambrian. The Geological Disposal Facility on the other hand, and its cache of nuclear waste, is a not-yet-built haunted house to be inserted into the past, but one that will definitely outlast us. Maybe it’ll be uncovered by future inhabitants of the planet who won’t know what to make of the tomb of energy ghosts. Thinking through this lens of inter-epochal haunting prompts another way of thinking about living with, and on, the planet, and of reckoning with a diminishing future: what ghosts do we want to make?

Jacob Bolton

This essay was commissioned by West Coast Photo Festival 2021 to accompany Mishka Henner and Vaseem Bhatti’s project Energy Goast: a ‘nature awareness brand’ revolving around the West Coast of Cumbria and its neighbouring landscape, The Lake District. Against the looming backdrop of natural disaster, Energy Goast explores the explosive origins of the Cumbrian landscape and the occult myths generated by its military and energy infrastructures.

West Coast Photo Festival launches this Thursday 7 October, and runs until Sunday 7 November 2021, at Cooke’s Studios, Barrow Market Hall and Florence Arts Centre, Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria.

See Energy Goast in full over on Insta.

Images from top: Screenshort, Energy Goast instagram. Screenshot, text reads ‘Be More Outside’ National Parks Trust Website. A ‘Frost Fair’ in London, showing the river Thames frozen over in the Little Ice Age. Unknown, c.1685, Yale Center for British Art. From ‘Sellafield Ltd Water Use’, showing water licenses (usage is redacted), internal document, October 2014. Screenshot, Geological Disposal Facility Virtual Exhibition. Natural Nuclear Fission Reactor, Oklo, Gabon. United States Department of Energy.

[1] Pearsall, W. H., and W. Pennington. “Ecological History of the English Lake District.” Journal of Ecology 34, no. 1 (1947): 137-48

[2] John Dower, A Report to the Minister of Country Town and Planning, 1945

[3] Zalasiewicz, Jan, Colin N Waters, Anthony D Barnosky, Alejandro Cearreta, Matt Edgeworth, Erle C Ellis, Agnieszka Gałuszka, Philip L Gibbard, Jacques Grinevald, Irka Hajdas, Juliana Ivar Do Sul, Catherine Jeandel, Reinhold Leinfelder, Jr Mcneill, Clément Poirier, Andrew Revkin, Daniel Deb Richter, and Will Steffen. “Colonization of the Americas, ‘Little Ice Age’ Climate, and Bomb-produced Carbon: Their Role in Defining the Anthropocene.” The Anthropocene Review 2, no. 2 (2015): 117-27.

[4] Hecht, Gabrielle. 2018. “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence.” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 1: 109–141.