John Moores Painting Prize 2020: Paranoia, Close-Up

For the latest in a series commissioned exclusively for us by the John Moores Painting Prize, Mike Pinnington responds to George Wills’ Paranoia, an artwork which gets under the skin of cinema and one of its most powerful innovations: the close-up…

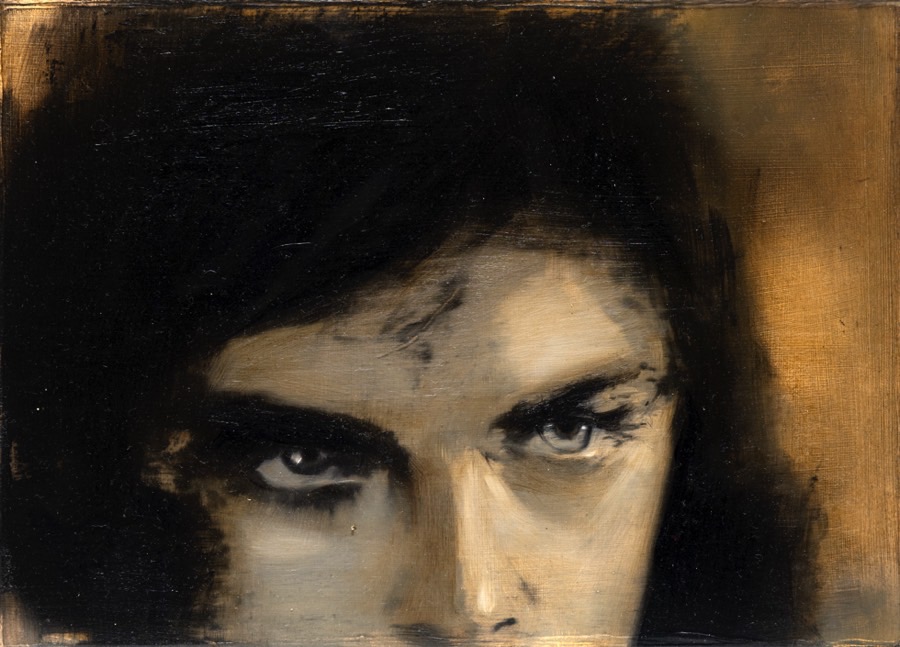

The woman looks up and outward, her hard, clear eyes steely and emotive. So much meaning communicated with so little; though nothing is visible beyond the narrow crop of her face, the scene screams narrative potential. Is that a retort or an accusation about to be hurled? A warning, maybe? Or something more, shall we say, terminal? Just who is the subject of her glare? A lover? A friend out of line? I’m glad it’s not me. One thing I know, as conveyed so effectively by George Wills’ painting, Paranoia (2020), is that the power of the extreme close-up is incontrovertible; it has endured for a reason. Since the early days of cinema, it has been used to frame mood, zeroing in on emotion. It allows us to get under the skin of those on-screen, to experience at one remove their fear, joy, bemusement, pleasure – and, indeed, their paranoia.

First employed by Hollywood pioneers such as DW Griffith, the close-up is like shorthand, a fast track into a character’s intimate space. When Griffith was challenged by his studio paymasters as to why he was putting only a fraction of his stars on screen in certain shots, he said that he employed the close-up to beckon the audience in. By “using what the eyes can see”, he brought cinema-goers closer to their idols than ever before. Further, the close-up tells us who and what is important in one intense shot, doing the most with the least. Director Darren Aronofsky has called the close-up “an overlooked great invention of the 20th century. The fact that one can stare into someone’s eyes without being self-conscious is a great gift to all of us. It’s why I love cinema.”

But what does it mean when the form’s visual language is adopted, as in the case of Wills, by art? By no means a new question, the proliferation of, first photography, then moving pictures, led John Stezaker to ask, “How can you be an artist in a culture of images?” For the celebrated collagist, it has meant a life-long investigation – of no less than truth, memory, and modern culture. Arguably, each of those elements is present in Wills’ painting, which borrows so successfully and unashamedly from the language of cinema. Paranoia freezes the action at a crucial moment; it continues the long dialogue between art and film, between viewer and painting. The outcome is immediate and arresting.

“Art has mimicked everything about cinema”, says artist Mark Lewis. “The size, the scale, the means of production. This goes back to the idea of the mimetic impulse in art, its insistent attempt to look like something else.” While this is demonstrably true, an older, more powerful impulse is our urge to tell stories, to make sense of our lives and the lives of others. It’s central to what makes us human: a deep exchange between teller and listener, between film and audience, between art and viewer.

Paranoia is both exploration and celebration of the form that so inspired it. As provocative as it is generative, our brains look for and translate the patterns of information we find in the paint, leading us to ask and answer a myriad of questions. Who is this woman? Is she mere passive subject of the male gaze, or active protagonist in her own story? What led her to this point? And, critically, what comes next? Our urge to tell stories – to ourselves and others – means we can’t help but make connections in-between and around the available details, to forge new narrative worlds of possibilities, whatever the medium.

Mike Pinnington is a writer, and Editor of The Double Negative.

George Wills (b. Devon, 1995) studied Painting at Wimbledon College of Arts, with a brief stint in Braunschweig, Germany in-between, which deepened his interest in both European cinema and the tradition of Northern European image-making.

This new text has been commissioned by the John Moores Painting Prize and is part of a creative-critical series published exclusively by The Double Negative during April and May. Writers were given free rein and approximately 500 words to respond to any painting or paintings from the 2020 exhibition, and in any style, tone or format that they wished to use.

The John Moores Painting Prize provides a platform for artists to inspire, disrupt and challenge the British painting art scene. Established in 1957, it is the UK’s longest running painting competition. For over 60 years the John Moores has brought to Liverpool the best contemporary painting from across the UK and has over that time, developed a legacy of supporting artists at all stages in their careers – undiscovered, emerging and established. All entries are judged anonymously. The John Moores 2020 jurors were: Hurvin Anderson, Alison Goldfrapp, Jennifer Higgie, Gu Wenda and Michelle Williams Gamaker.

See the exhibition yourself via their virtual tour!

Image: Paranoia (2020) by George Wills