Duty Of Care: Why Support Parent Artists?

“Structural inequalities exert pressure upon individuals.” Elaine Speight on a necessary and urgent rethink in considering the needs of cultural workers with children…

Early last February, I was invited to give an online talk at an international conference. Five months into maternity leave and with a three-year old at home, I worried that the children would escape their father’s supervision and make a cameo appearance. Fortunately, my presentation was uninterrupted. However, a few weeks later the country was in lockdown, I was back at work and both children were regular features of my many online meetings. As I spoke to colleagues with the baby asleep on my chest, or my daughter pulling faces at their children on the screen, there seemed to be some benefits to lockdown. The behind-the-scenes juggling of family and work was now not only visible, but ameliorated by flexible working patterns, the use of technology and the absence of commuting. Despite the challenging circumstances, it was easy to feel that a cultural shift was taking place in favour of working parents.

As an academic with an indefinite contract, though, my perspective was skewed, and the reality was very different for many other parents. Within the visual arts, the pandemic has had a particularly devastating impact on artists. When galleries closed their doors and furloughed their staff at the beginning of the first lockdown, many artists, alongside other freelance cultural workers, had work cancelled or postponed and lost income as a result. The need to home-school or entertain children during lockdown deprived them of the necessary time to make new artwork or to plan and fundraise for projects, potentially damaging their future career prospects.

Such problems, which have been exacerbated by Covid, are symptomatic of the precarious status of artists. As Dr Susan Jones points out, artists constitute a “ubiquitous pool of talent” which the visual arts industry can dip into, with no obligation to provide the same rights or support enjoyed by the cultural gatekeepers that it employs, such as curators and gallery directors. As freelance workers, for example, artists are excluded from the type of generous maternity leave which I had access to. Similarly, the unpredictability of artists’ working patterns and income means that regular childcare can be logistically and financially unfeasible.

When I first discussed writing an article about the problems faced by parent artists, some of the responses I received were along the lines of, “okay, we know things aren’t stacked in their favour, and universal free childcare would be great … but so what?” To a certain extent, this attitude is understandable. After all, people don’t have to have children, nor for that matter to become an artist, and if they do, they enter into it with at least some awareness of the sacrifices involved. The problem with this view, however, is that it fails to acknowledge the different ways in which structural inequalities exert pressure upon individuals.

Claire Weetman, an artist and mother of two based in St Helens, describes how, in the same way that the pandemic has exposed existing social disparities across ethnic, class and gender lines, “precarity is an issue which is heightened once you become a parent.” The economic uncertainty, lack of routine, expectations to work to tight deadlines and non-standardised hours associated with art production are perhaps manageable, if not desirable, for a person with no caring responsibilities. However, for someone with a family to support, particularly if they lack an economic safety net or support network, or are facing other forms of discrimination, such demanding working practices can be impossible to uphold.

The effects of parenthood are also informed by how well-established an artist is. When Weetman gave birth to her daughter in 2014, she had been working as an artist for more than 10 years and had built professional relationships with several arts organisations. As such, not only was she able to take maternity leave in the knowledge that she had work scheduled for her return, but she also had the confidence to negotiate the conditions needed to support her new role, such as flexible working patterns and a higher rate of pay – which she acknowledges younger artists would find more difficult to do.

In contrast, Laura Fooks, who is about to embark on a PhD exploring the experiences of mother artists, had only recently begun to practice as an artist when she became a mother in 2012 and found that her career stalled. “Where my associates would be networking at opening nights or exhibitions or lectures,” she explained, “I would be unable to attend due to my mothering duties.” Accessing spaces for creating work with a child in tow, including for her master’s degree, was also impeded by the fact that most studios and academic facilities are not insured to accommodate children.

Alongside access to working space, finding time to make artwork can also prove challenging. Weetman describes how “the bittiness of time between school runs can be a struggle. You have to work in timeslots, and it can be difficult to switch into a different type of headspace.” While this scenario will be familiar to many working parents, the necessity to maintain a practice presents an additional challenge for artists. Current commissioning models tend to give the impression of artists as service providers – as workshop facilitators, creative consultants, or urban realm enhancers. Yet, hidden from view are the many hours of unpaid ‘studio time’ necessary for thinking, testing, and developing ideas. For parents, particularly women who tend to do most of the childcare, retreating to the studio can feel like an indulgence. “It’s easier to say, ‘I’m going out to teach, to do this work’ rather than ‘I need an hour to think about something’”, explains Weetman. “It’s also easier to schedule childcare when it’s for something specific.”

In the absence of much-needed structural change, there are, of course, practical ways to make life easier for parent artists. Organisations such as Lancaster Arts and Bluecoat in Liverpool already ensure that childcare costs are built into project budgets. The latter have also hosted exhibition openings at family-friendly times, accommodate children during meetings and exhibition installs and occasionally hire child-minders. Similarly, Heart of Glass in St Helens employed early years practitioners to run a free crèche at their (pre-pandemic) annual conference. More recently, they have been mindful of home-schooling commitments, such as those of The Faculty North – a learning programme for artists developed with In-Situ – broadcast at times which suit participants.

While such measures are welcome, it is important to remember that the challenges faced by parents are not solely related to childcare. Being a parent is an intensely embodied, emotional and, for women, hormonal experience which can have a huge impact upon an artist’s practice. Fooks describes how, following the difficult birth of her first child, she suffered from post-natal depression and struggled to reconcile her new role as a mother with her former sense of self, including her identity as an artist. It was only after the “positive birth experience” of her second child four years later that she regained her “drive to create”, and began to use her skills as an artist to expose and come to terms with her previous trauma.

To support parents, arts organisations need to acknowledge that parenthood can affect artists in different ways and to accommodate such difference. For Helen Wewiora, Director of Manchester’s Castlefield Gallery, this means taking a human approach to commissioning by “working with artists as people.”

“We do our best to get to know the people we are working with,” Wewiora explains, “to understand, to listen, to try and be responsive.” In 2017, Castlefield invited Ruth Barker to undertake a residency alongside fellow artist Hannah Leighton-Boyce. Mindful that, as well as recovering from the difficult birth of her second baby, Barker also had a pre-school child and a full-time working partner, the gallery spent time developing an approach that “felt right and worked for her.” As well as housing Barker and her children in a family-friendly home and organising childcare, they also divided the residency into a series of shorter visits, which took place over an extended timeframe, and enabled Barker to undertake some of the work remotely. As Wewiora points out, supporting artists in this way “isn’t rocket science. It just demands time, thought, care, good communication, and some flexibility within processes.”

It is also important that organisations take an inclusive approach to support. Bluecoat’s Head of Programme, Marie-Anne McQuay, makes the point that “parenting includes the LGBTQ+ family. Also, caring for older people or relatives can be a more invisible strain on time and availability.” This sentiment is echoed by Zara Saghir, a recent MA Fine Art graduate, who works with arts organisations in Lancashire. Saghir lives at home with her parents, but, due to her mother’s Bipolar disorder and her father’s long working hours, she is the main carer for her younger siblings. “It can be awkward telling people that you need to leave early to collect them from school or can’t make an event because you need to take one of them to the dentist,” she explains. “People don’t understand why it’s my responsibility, they think I’m not taking my work seriously.” And yet, organisations could alleviate this anxiety by taking the initiative to “open up a conversation”.

“At the beginning of a project, it would really help if they asked whether you had any responsibilities,” Saghir suggests, “and helped you plan your work alongside family commitments.”

If we believe that the visual arts should reflect the diversity of our communities, and not simply be populated by people with the economic and cultural means necessary to build a career in the artworld, then supporting artists with caring responsibilities of all types is essential. Organisations across the region are making concerted efforts in this area, but support is usually provided on an informal basis and such values need to be enshrined into organisational policies. To a large extent, the will to do this exists, and inspiration and advice is available nationally from groups such as Spiltmilk Gallery, Creative Young Carers and Motherhouse Studios. As venues prepare to reopen, it’s essential that the affordances made for the caring responsibilities of arts employees during lockdown are not lost, but extended to all, and that the artworld finally embraces its duty of care to its most fundamental workers.

Elaine Speight

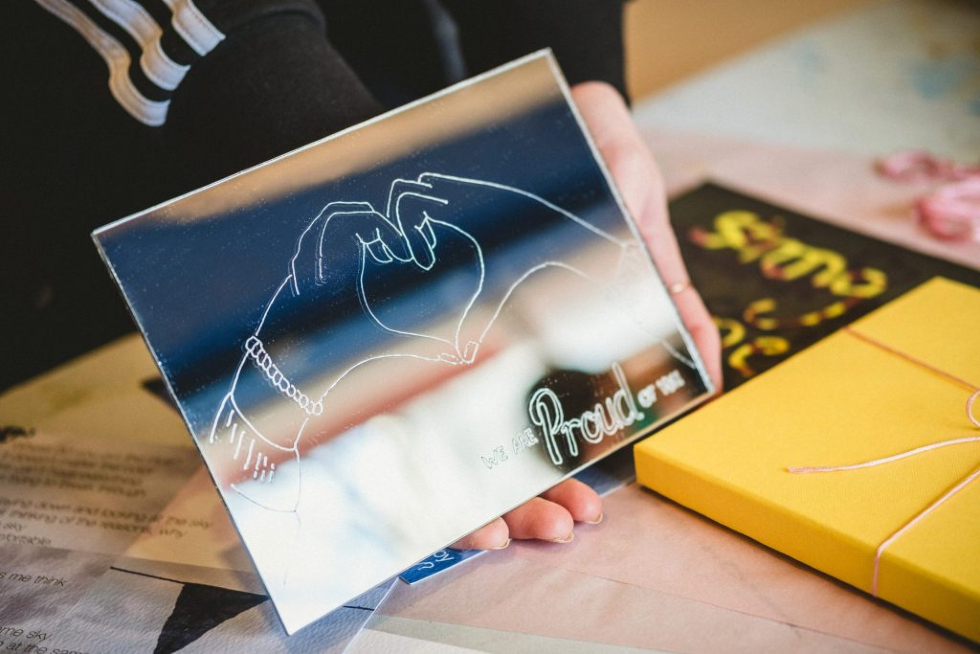

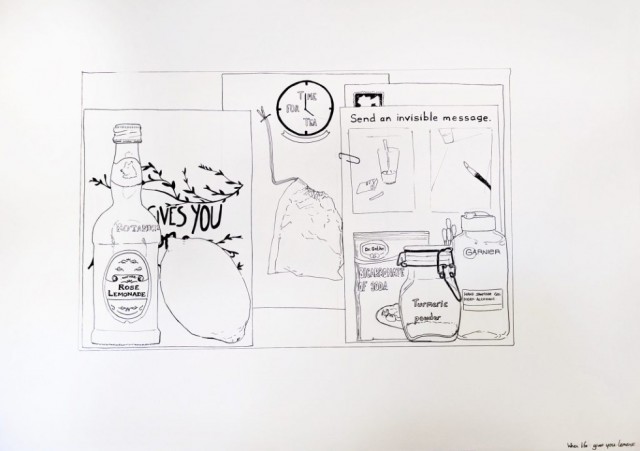

Images, from top: An edition of 100 gift boxes distributed as part of Walking Together/Walking Apart, Claire Weetman. Made with women from Refugee Women Connect. Commissioned by Heart of Glass, 2020. Photo by Radka Dolinska; When life gives you lemons, illustration of resource packs distributed as part of Walking Together/Walking Apart, Claire Weetman. Made with women from Refugee Women Connect. Commissioned by Heart of Glass, 2020; No space, mixed media, Laura Fooks, 2019; What is MINE? What is YOURS? What is OURS, Zara Saghir, 2019

This article is part of the series, ‘New Critical Writing North West: Voices on Lancashire & Cumbria’: new pieces of critical writing which review and examine issues relating to the contemporary visual arts in Lancashire and Cumbria. The series has been commissioned by Contemporary Visual Arts Network North-by-NorthWest (CVAN NbyNW), in partnership with The Double Negative